We all know that selective word-choice can enrich writing (Academy, 2021). It will lend clarity to a story, deepen emotional attachment to a character, and broaden the understanding of a topic. Contrastingly, misused vocabulary can harm the message of a text. And, weak words will water down its substance. Therefore, building a thorough understanding of a wide array of words will prepare students for increasingly effective communication. As it turns out, I have a game that will make your learners crave vocabulary-building.

Would you like your students to beg you to learn new robust vocabulary? Try Balderdash.

I call the game “Balderdash.” (There is a board game version, but I’ve never used it. From the description, it seems to contain the gist of what I present here.) The name is unique enough to spark interest and be memorable. It also lends itself to the core of the game; Playing with unknown words.

This is how I introduce the game to my students. I start off by explaining that this is a game of definitions.

“How many times have you been reading an entertaining story, and really enjoying yourself; Then you come across a word that trips you up? All of a sudden, you don’t know what is happening. Why are the characters acting so weird? What did you miss? They aren’t always big words, but misinterpreting the meaning of a word can turn a heretofore simple tale on its head (irony in italics;).

“In this game, you will be presented with a word that you probably don’t know. That is okay. You aren’t supposed to know what the word means. If you DO know what it means, or if you think you know what it means, that is okay, too. But, don’t tell anyone. You can earn points by writing down a definition that is really close to accurate.”

Here’s how it works

- Have a list of your students handy.

- Hand out index cards or sticky notes. Tell students to keep the papers UNFOLDED. Also, do not write on the cards until instructed. (They must look the same.)

- Have your students write their names on the top. Everyone should use pencil, and don’t do anything to your card to make it appear unique. (You will understand why in a minute.)

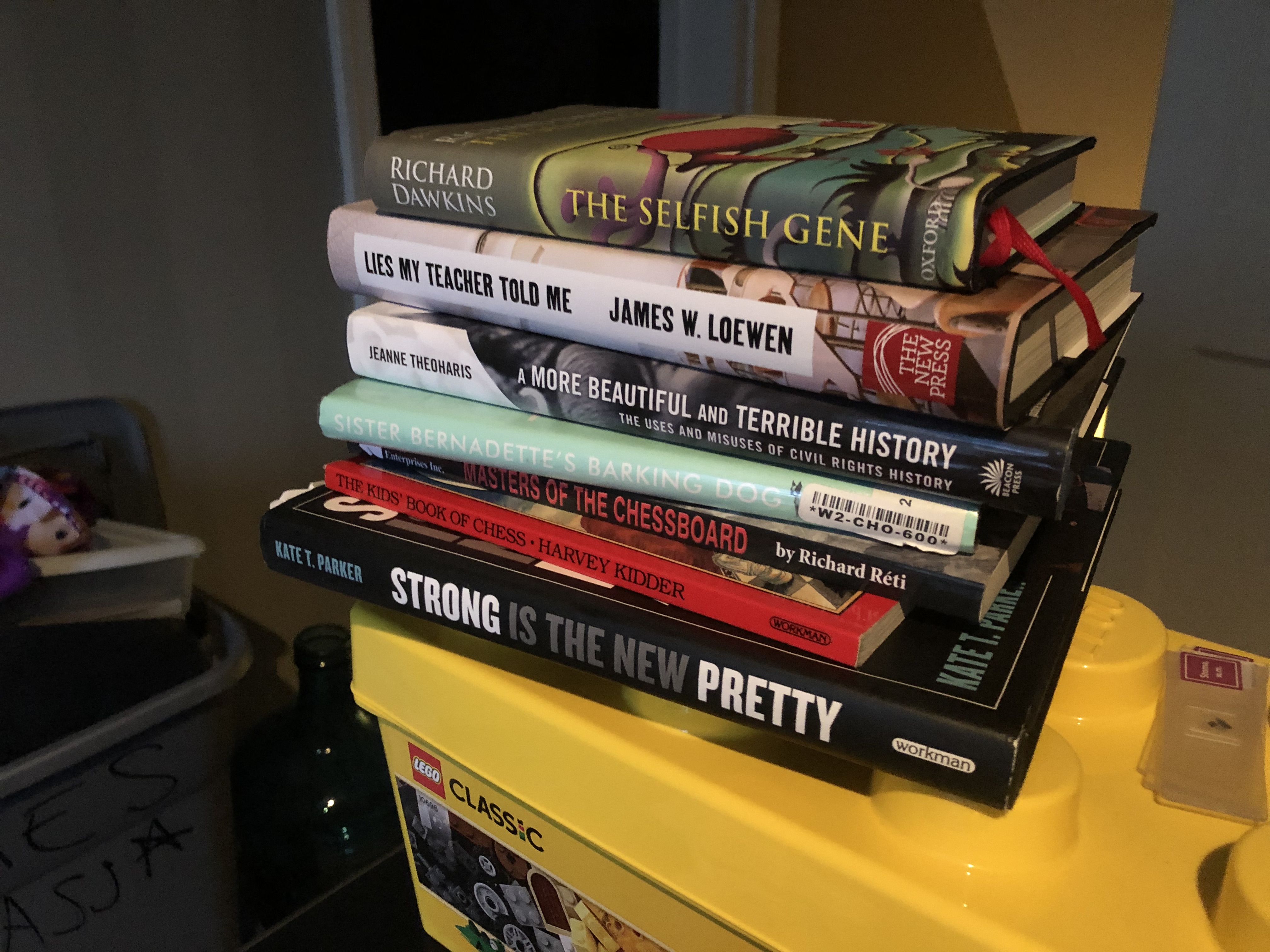

- Next, come up with a word that students will not know. You could begin with “balderdash.” This would make the game that much more memorable! You could use a vocabulary word from a list of words you want the class to learn. You could even flip through the dictionary, looking for tough words.

- Write the word on the board, so that everyone spells it correctly. You may want to write down some phonetic tips. I will sometimes explain what part of speech it is; perhaps even a hint. (i.e. This is a noun; and although this game might be named “Balderdash,” that isn’t what it means.)

- Tell the students to make up a definition for the word. Explain to them that their peers are going to vote on which definition sounds most likely to be true or accurate.

- While the students are writing their definitions, you look up the true definition of the word. (I don’t recommend relying on your own interpretation. Even if you do understand the word, it is best to deliver the scholarly definition first.) You will need to put the definition into kid-friendly language. Your definition will need to match the ones that students hand in.

- Walk around and collect everyone’s index card. I recommend using a bucket or top hat for this.

- Read through the definitions to yourself, making sure that you understand what they say and are able to read them fluidly. You don’t want to supply any “tells” that one is NOT the accurate definition. If there are any that are similar to the actual definition, provide that student a point and remove the definition from the pile. (Reading 2 of the same definitions would let them know they are the true definition.)

- Next, place them back into the hat or bucket. Pull one at a time and read it. Do this once through without any voting.

- Then, repeat the process, but after each reading, have students raise their hands if they think it is the correct definition. You can only vote once, and you can’t vote for your own definition.

- Give the pupil who produced the phony definition a point for each vote. Whoever votes for the true definition also gets a point.

- After each round, share who earned the most points and the real definition.

In the same way a serious athlete might take creatine supplements to boost muscle-building ability in the body during intense exercise (Creatine, 2021), using games to increase enthusiasm for definition development can motivate kids to grow their vocabularies. Rather than get fatigued when faced with unknown words in texts, your students will view these as opportunities for growth.

An athlete takes creatine supplements to prepare their body for doing a little bit extra in each exercise, making the workout that much more beneficial. Balderdash is a reason for collecting large, complex, unfamiliar words, and tucking their meanings into memory banks for future use. Plus, it’s a lot of fun! game

Sources

Academy, E. (2021, November 12). Word Choice in Academic Writing: Tips to Avoid Common Problems. Enago Academy. https://www.enago.com/academy/word-choice-in-academic-writing-tips-to-avoid-common-problems/

Balderdash Board Game – the Game Of Twisting Truths. (n.d.). Mattel Shop. https://shop.mattel.com/products/balderdash-cfx43

Creatine. (2021, February 9). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements-creatine/art-20347591

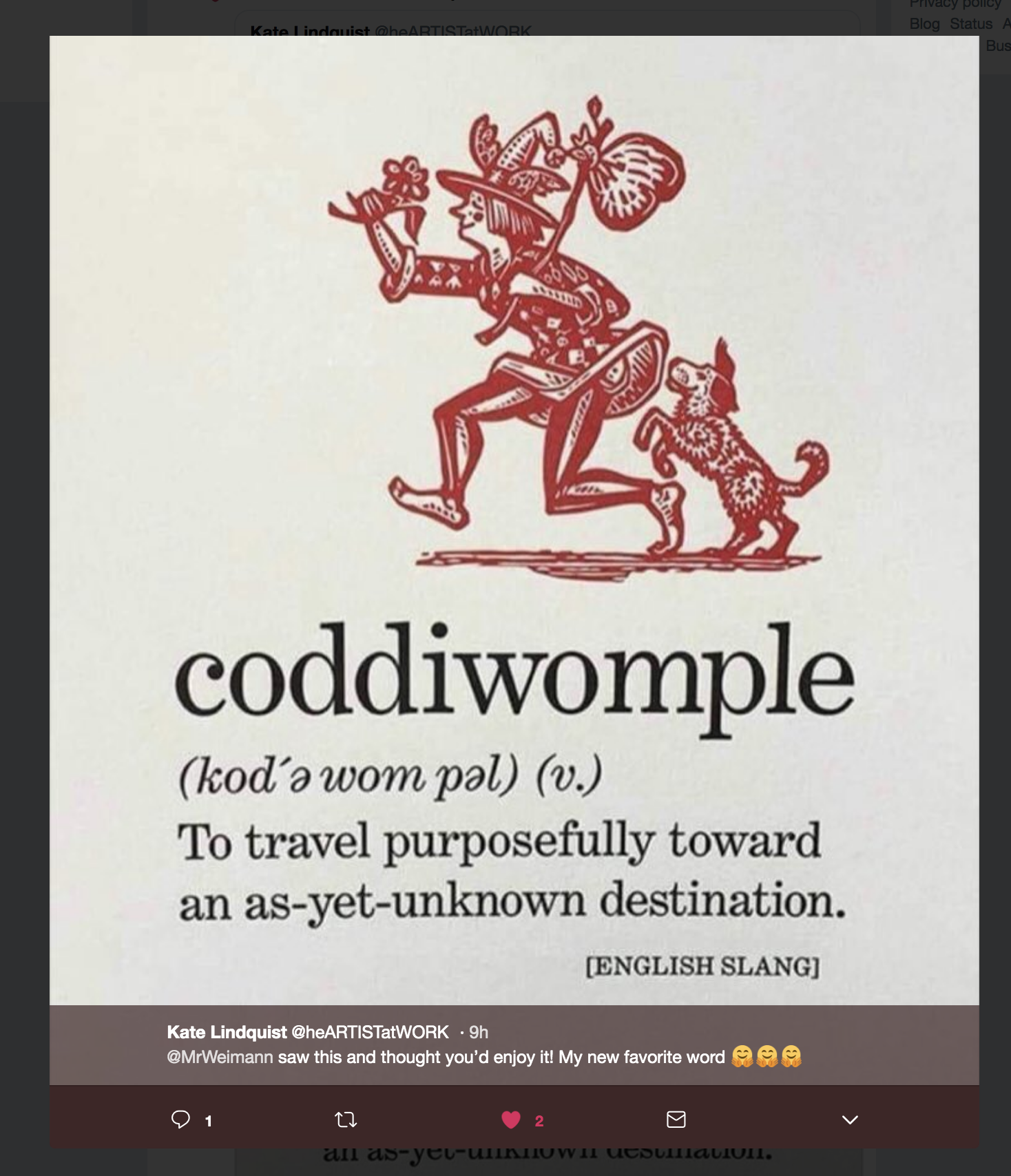

The word was

The word was

With sentences longer than the paragraphs my third graders write, this text presents descriptive writing that transforms the 21st century classroom into a one-room schoolhouse in a comfortably lazy, quiet, rural town. Incidentally, Sleepy Hollow is an actual town. If you cross the Tappan Zee Bridge, a word Irving includes in his text, you will see signs for it.

With sentences longer than the paragraphs my third graders write, this text presents descriptive writing that transforms the 21st century classroom into a one-room schoolhouse in a comfortably lazy, quiet, rural town. Incidentally, Sleepy Hollow is an actual town. If you cross the Tappan Zee Bridge, a word Irving includes in his text, you will see signs for it.  one of our lessons was to use Mr., Mrs., Miss, or Ms. along with the last name (cognomen) when speaking with adults, or find out how the adult would like to be addressed.

one of our lessons was to use Mr., Mrs., Miss, or Ms. along with the last name (cognomen) when speaking with adults, or find out how the adult would like to be addressed.