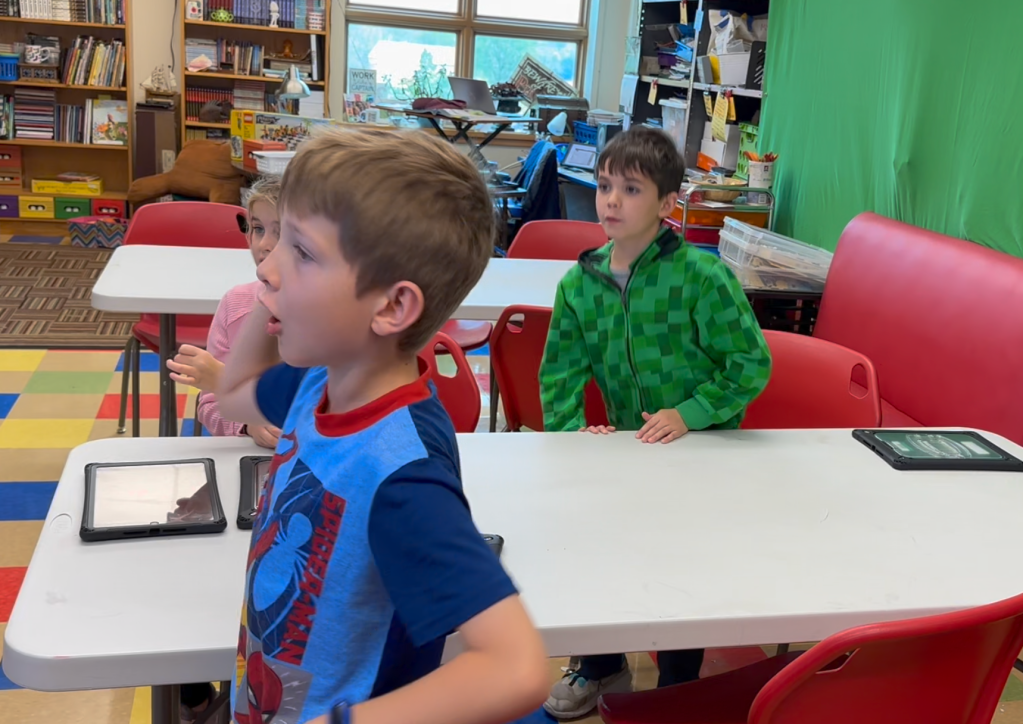

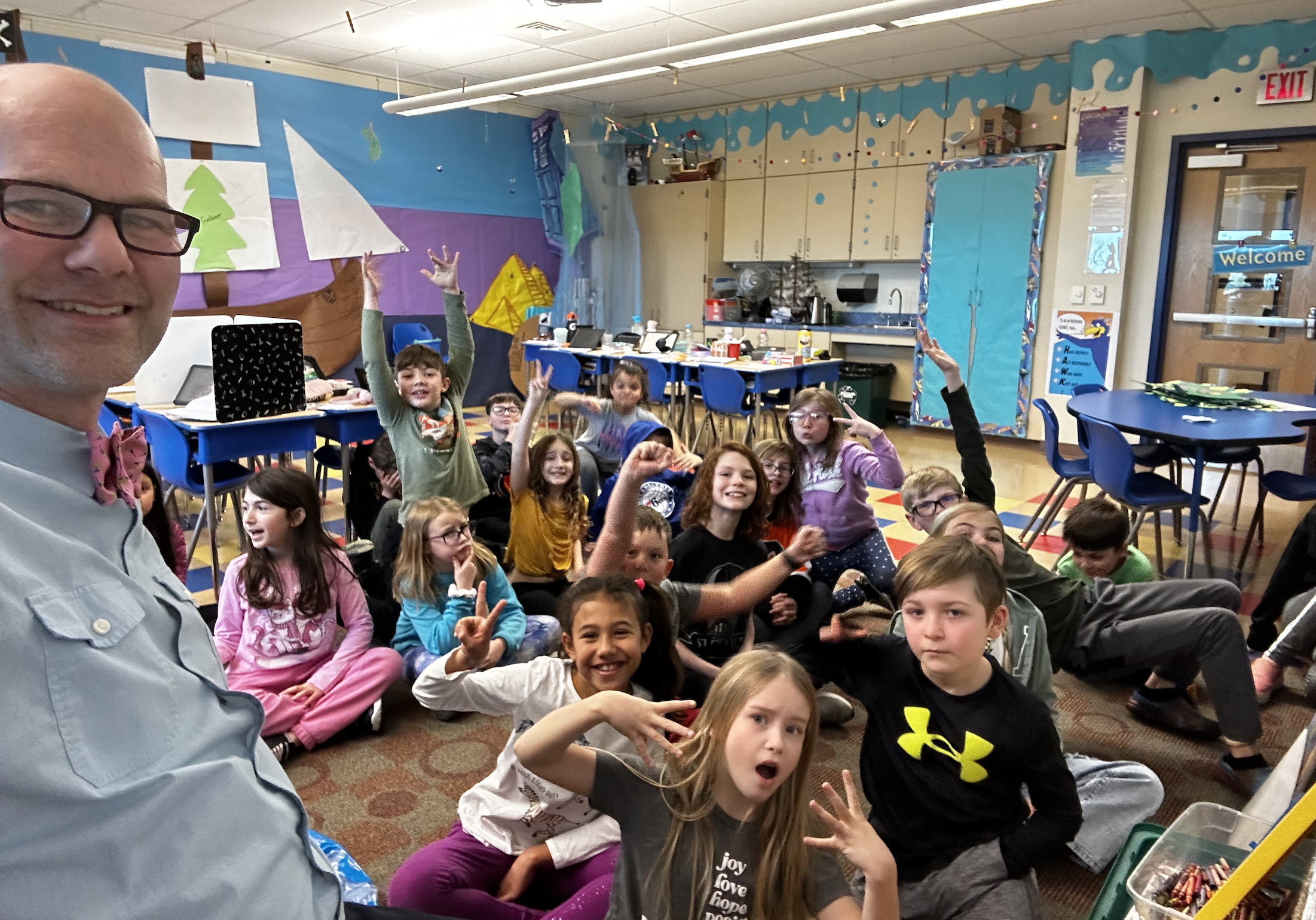

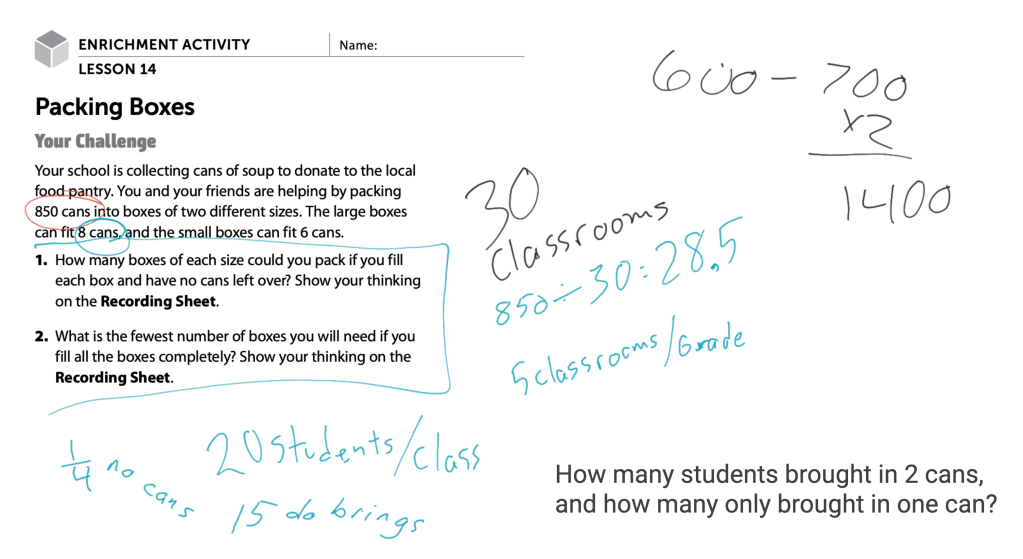

“Where did the 850 cans come from?” I was in the middle of sharing the iReady enrichment lesson (14) with my fourth graders when one of them asked me this question.

Have you ever had a student ask a question in order to postpone learning? If you’re a teacher, then that’s a silly question. Of course!

This is one of the few things that I remember from my elementary and middle school days. It was a thrilling challenge to try to come up with just the right topic or question that could throw the teacher off track.

We would hope and pray for a story. Then, we would artfully flatter and ask questions that would lead our pedagogue down the rabbit hole of memories, further and further… away from the lesson at hand.

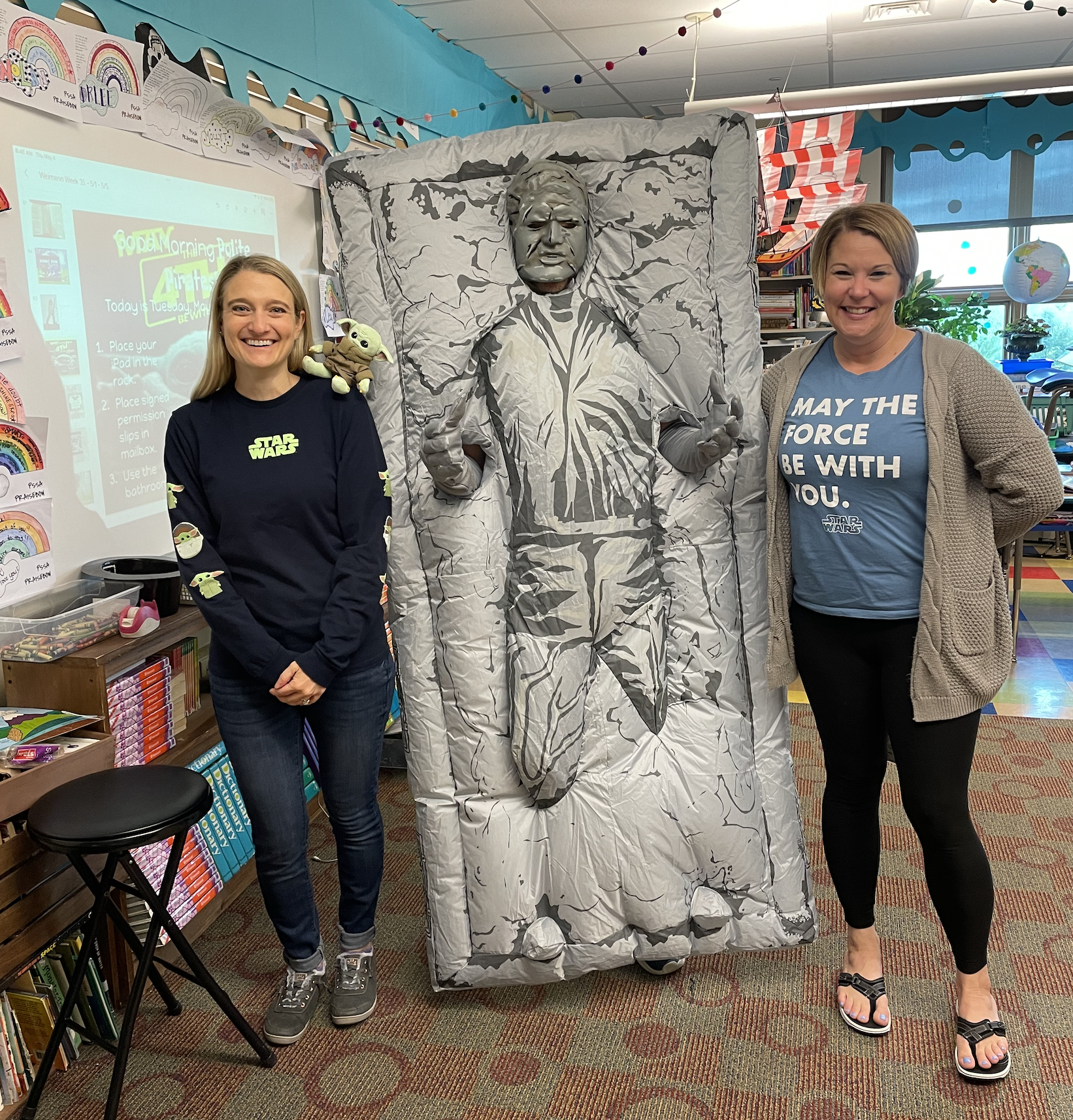

Fast forward forty years. Today’s students still play the same tricks on their teachers! This past week I was engaging some fourth graders in math enrichment, when one of them tried steering me off task. Little did they know, that I practice Pedagogical Aikido.

Redirecting Energy

Aikido is a form of martial arts that is known for using an opponent’s energy (ki) against them. Masters of this study practice redirection.

Although I have not formally studied Aikido, I love its principles and attempt to use the philosophy of redirecting thought and energy within the walls of my classroom as much as possible.

For example, the other day when my student asked about the origin of the 850 cans in our math problem, I allowed the student to think that he had derailed the lesson. I told him that this was an excellent question. “850 cans is a lot of cans. Where would a school get that many cans for a fundraiser?”

The martial art Aikido uses a triangle to teach the redirection of energy. There are three components that work together to use an opponent’s attack against them, saving your energy and neutralizing the situation. It all starts with Balance, known as tachi waza (Aloia, 2020).

“How many students does our school have?” I asked the class.

I could have squashed the student’s inquiry, telling him something like, “I don’t know where the number of cans came from. It’s hypothetical. Let’s just move on!” Or, “It came from Curriculum Associates, the authors of our math program. Don’t ask silly questions.”

If I had done that, I would have disrespected the student. A dismissive teacher or one who blocks the question head on is too hard, too strong; the lesson too one-sided. By allowing for the question in the first place, and then entertaining it, I had my center of gravity low to the ground. My metaphorical feet were spread wide apart and knees bent. The question didn’t topple my lesson. I was balanced.

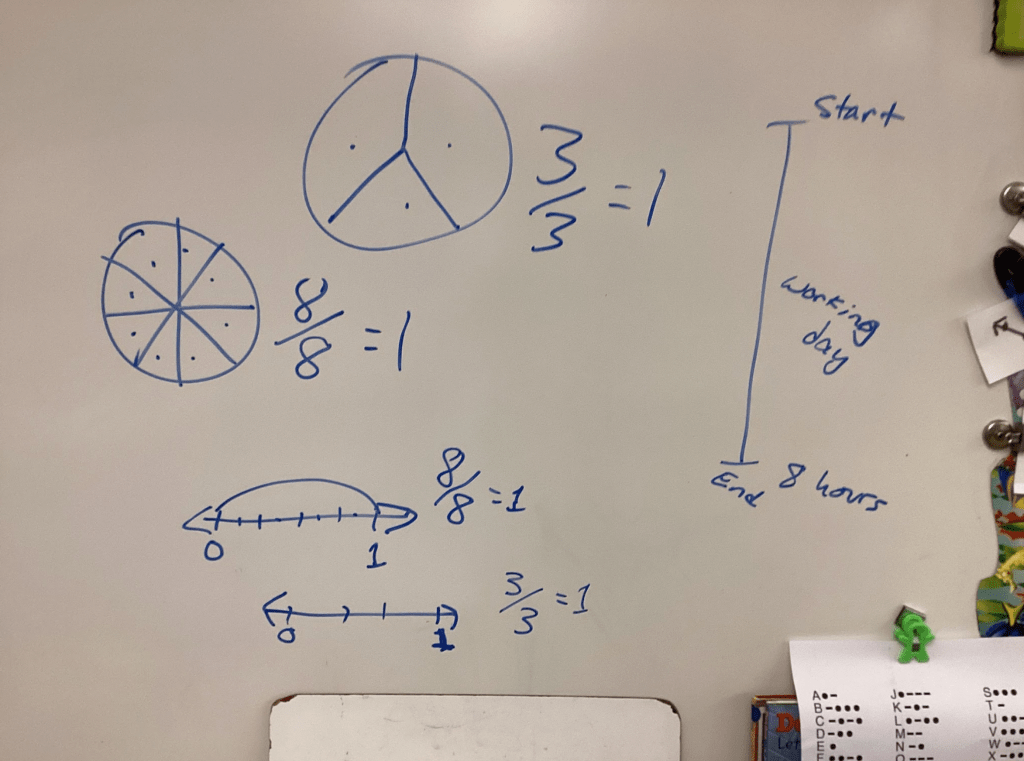

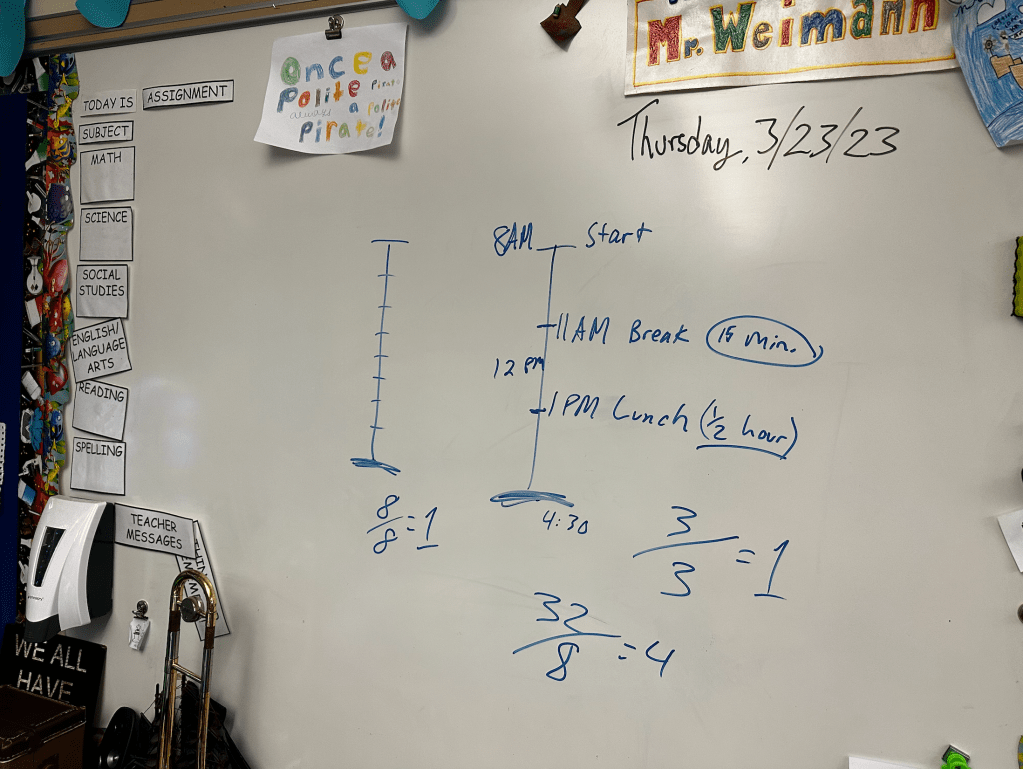

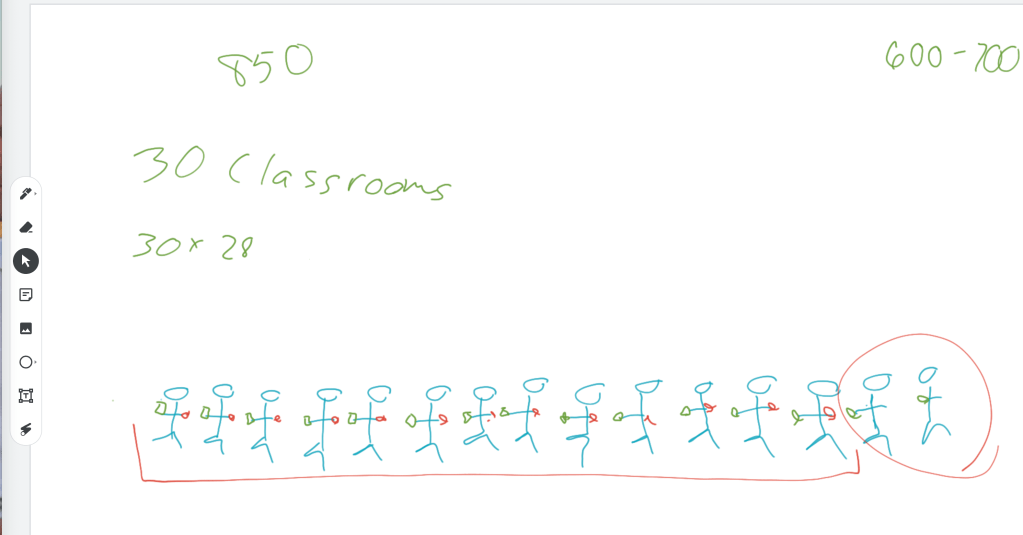

In answering my question, the students were surprisingly accurate. Our school has around 700 students. “How many cans would we have if each student brought in one can?” I prompted. That was easy. “But, not every student will bring in a can… And, some will bring in more than one.” The easy back and forth of these simple concepts established a flexible, down to earth ease of thinking. It also revealed the problem. We don’t know where the 850 cans came from.

Next, it was time to Break Balance. This is the second part of the redirecting-energy triangle. “The opposite of balance is imbalance, or kuzushi. To break an opponent’s balance, one must first redirect their energy to one’s own advantage” (Aloia, 2020)

I shouldn’t be surprised, but I was very impressed, nonetheless, at how quickly my students figured out how many classrooms our school had. It was the advanced fourth grade math students receiving enrichment, after all!

I had begun the imbalance kuzushi by getting the class to come up with the total number of classes in the building. After figuring out that our school has five classrooms per grade and our school teaches six grades, if you include kindergarten, we discovered that there are 30 classes represented.

“Let’s say that our school collected 850 cans. How many cans would each class bring in?” The students had no clue where to start.

Antonio Aloia (2020) explains that kuzushi has two arms. The physical off-balancing of an attacker, parrying the opponent’s strike and redirecting the momentum of the assault, coupled with a strike of their own is what one normally thinks of when imagining Aikido. Um, of course there isn’t any literal physical contact with students, let alone “attacks,” but presenting this new problem of dividing up the number of cans by the number of classrooms was a cogitational assault of sorts.

The other arm of kuzushi is a psychological off-balancing. This is where a martial artist would “Distract a would-be opponent by bringing their attention to something else, be it an object on a building or something farther away and behind the opponent” (Aloia, 2020). Pedagogically, this happened when I changed the student’s original question from “where” to “how”: “Where did the cans come from?” turned into “How could a school come up with so many cans?”

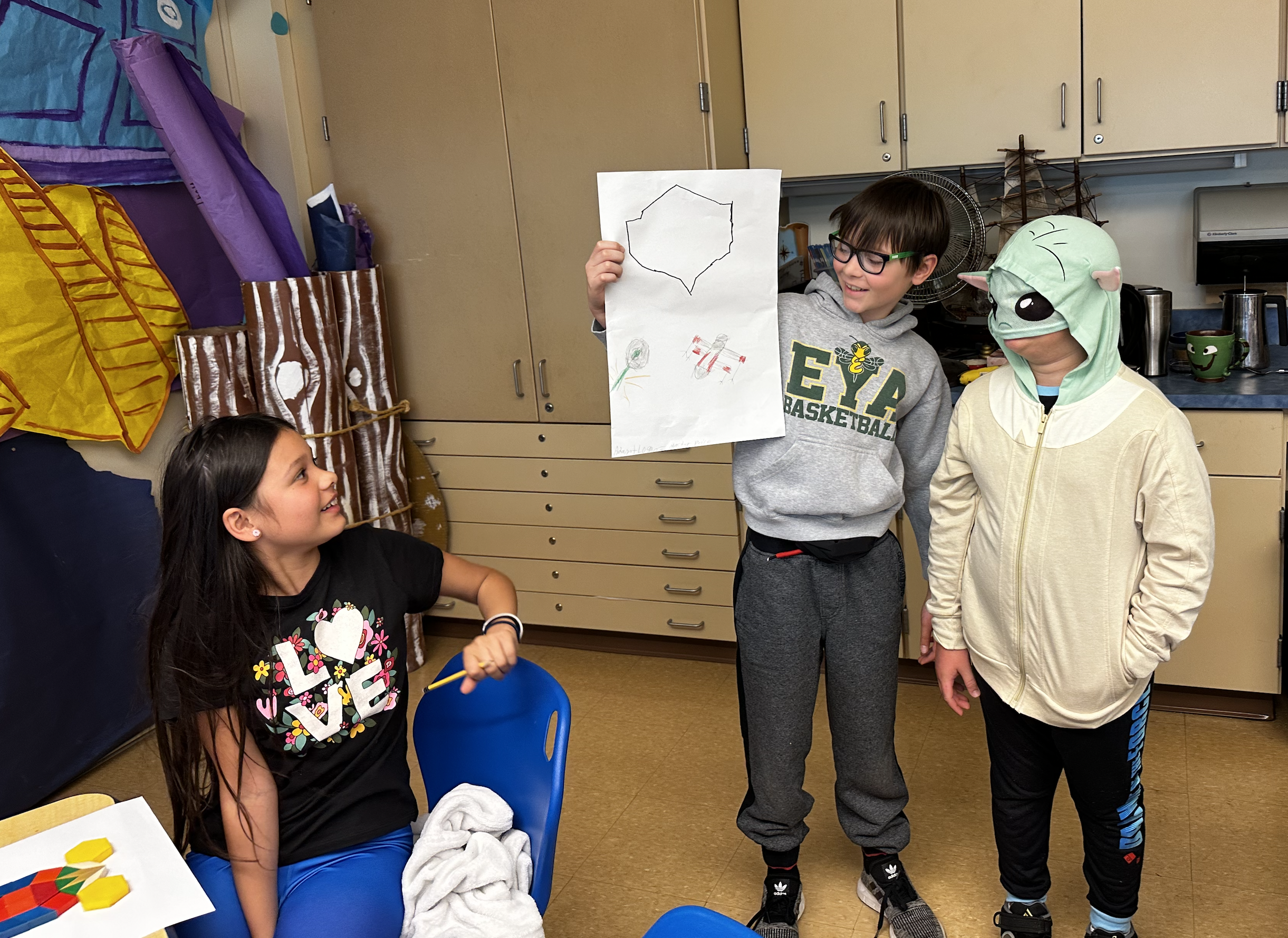

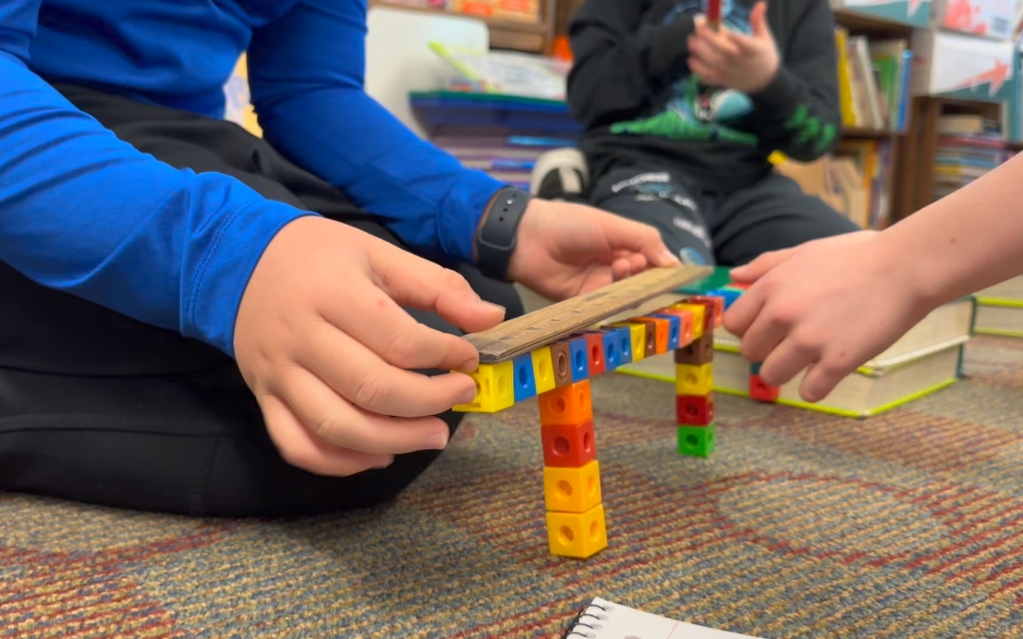

While the martial art of Judo involves throws, Aikido keeps your opponent tight and controlled. Perhaps counter-intuitively, it is concerned with the well-being of the attacker. So, rather than toss my students aside to flounder with the problem of dividing 850 by 30 on their own, I guided them through the process of figuring out the answer.

I asked them how many cans there would be if every class brought in 10 each; 300. “Okay, maybe that was the first week of the fundraiser. If each class brought in another ten cans during the second week, how many cans would the school have collected?” We were up to 600 cans. They were starting to catch on.

One of the students used Google to divide 850 by 30. Rather than scold him, I asked him if it were possible for any of the classrooms to bring in .333333 of cans. This was a silly question. “What happens with the remainder from the division answer?” I asked. They didn’t know. “For our purposes, we will assume that the students from every classroom brought in 28 cans. The teachers brought in the rest.” My students were okay with this explanation.

The third side of Aikido’s redirecting energy triangle permeates everything. It is ki or energy. Don’t think of it as power or force, though. Ki is more like momentum.

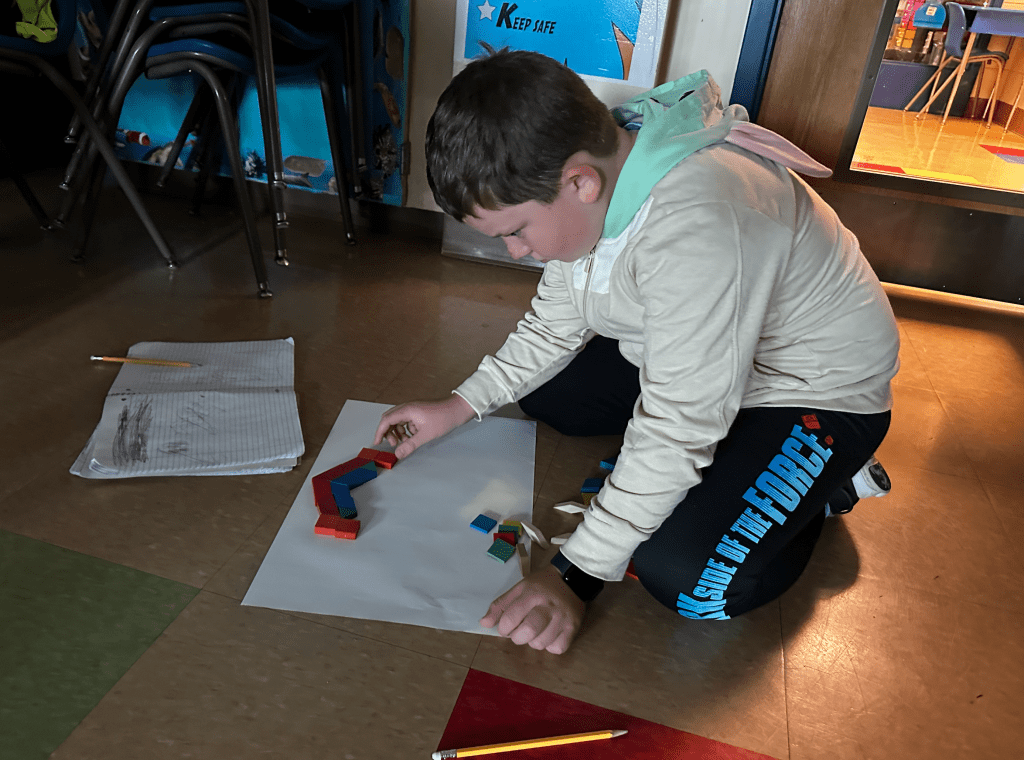

“How big are our classrooms? How many students are there in a classroom?” I got several answers on this. We decided to use the number 20. “Let’s say that a quarter of the students don’t bring in any cans. If the rest are responsible for bringing in 28 cans, how many brought in two and how many brought in one?” My students just looked at me. I told them to try and figure it out on their own, and then I’d show them.

One student crushed it, and I had her show the class what she did. Then I modeled drawing a picture to solve the problem.

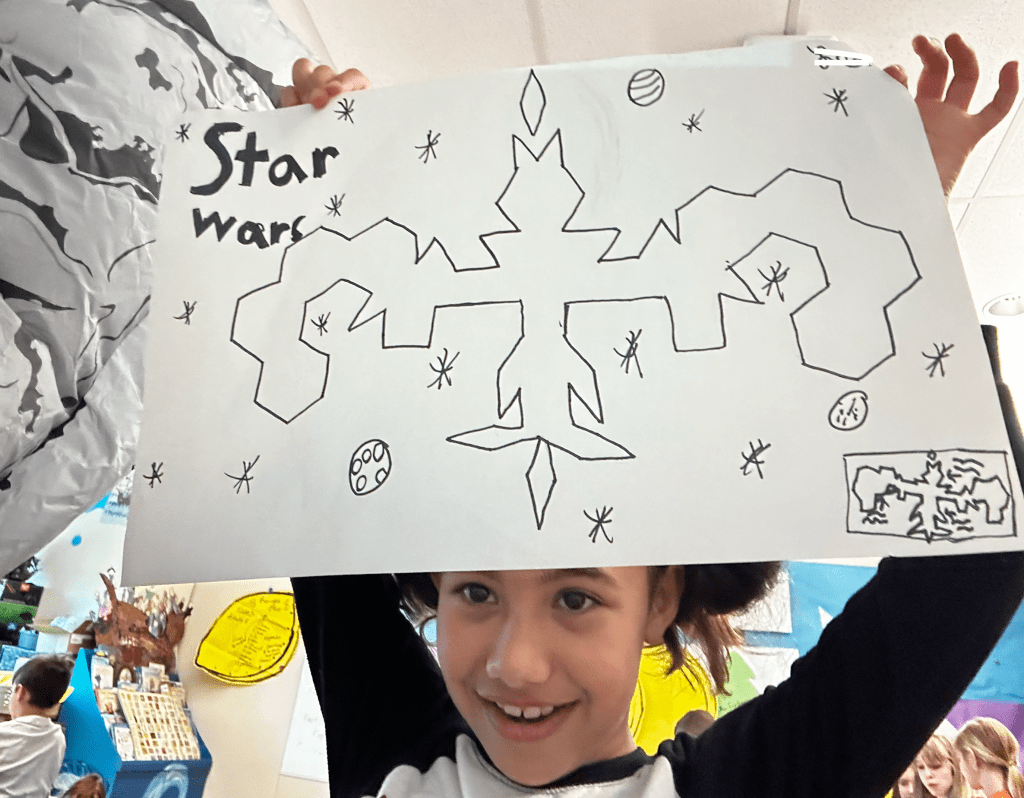

After all of this, I told my students, “Now that we have collected all of these cans, we need to put them in something to bring them to the food pantry that we are donating them to.”

“If Dylan went out and bought a bunch of boxes… Thank you Dylan! (Dylan is all smiles at this point; He may or may not have been the person to ask the question that started all of this;) And, if Dylan’s boxes are all the same size, holding six cans each, how many boxes would Dylan have to get?” I let them wrestle with that a little while.

When I was prepared to let them demonstrate their math on the board, I turned to the slide that had the original question on it. They reread the word problem as I decided on who would come forward to share their work first. A few students groaned and some others called out. “That’s the problem we just did!”

“Yeah?” I feigned ignorance.

I used someone else’s name when I told the story about getting bigger boxes; Ones that held 8, instead of 6 cans. “How many of those boxes were purchased?”

As it turns out, we never got to fully explore the last question, but a couple of students tried solving it in their heads. I had completely Aikido-ed them! Lol.

Source

Aloia, A. (2020, June 19). Reflecting on Jujitsu Pioneer George Kirby’s Advanced Techniques for Redirecting an Opponent’s Energy. Martial Arts of Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. https://maytt.home.blog/2020/06/19/reflection-on-jujitsu-pioneer-george-kirbys-advanced-techniques-for-redirecting-an-opponents-energy/comment-page-1/?unapproved=2695&moderation-hash=f6966939a4ca212a2123a94cabda8d13#respond