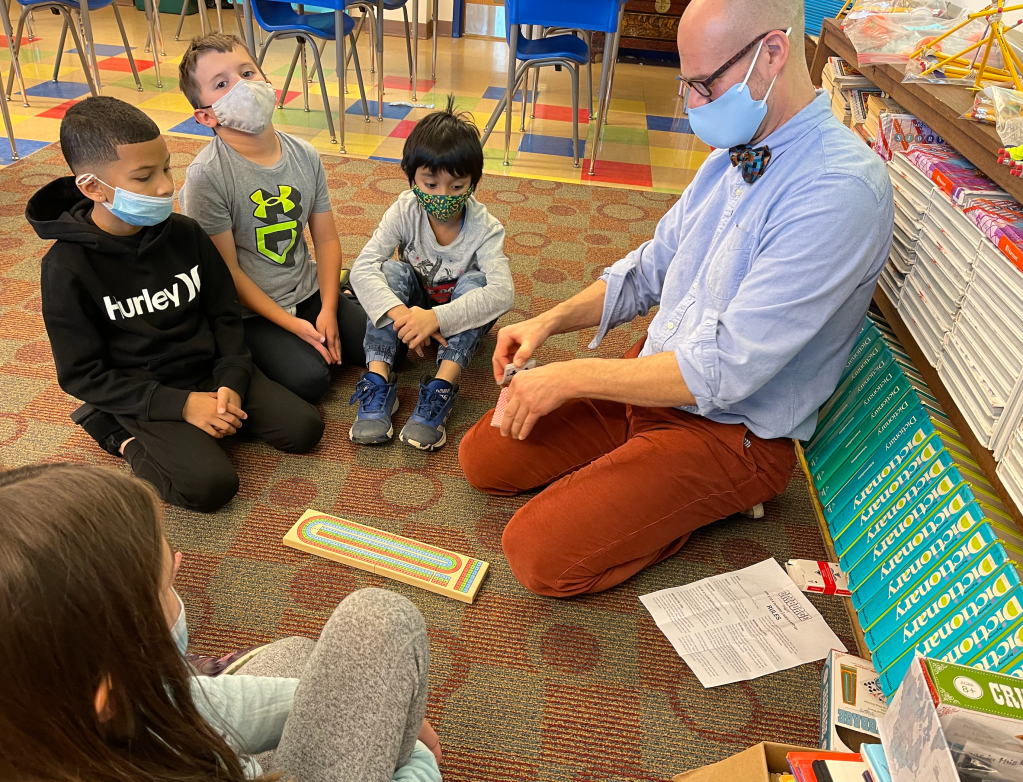

My second grade gifted students are very excited about reading Harry Potter. A couple boys talk about the books often. I’ve had to stop them before they give away any of the plot and spoil the literary experience for those who haven’t read as much.

The other day one of my students was pacing around the room conducting a monologue about quidditch. Everyone was working on wrapping up an end of the year project when this student took a break to stim.

Over the years I’ve had a few students who stim. It took me a while to understand what this was, and even longer before I was familiar with the term. Stimming is an abbreviation for stimulation. It is when a person uses sound, motion, touch, or other stimulating sensations to soothe the spirit. A person may sing to themselves, wave their hands, repeatedly run their fingers over a piece of fabric, or pace the floor. It usually involves repetition.

The National Autistic Society suggests four reasons a person may stim. They could be using their stim to self-regulate the amount of sensory input they are receiving. By making their own noise, they are blocking out other sounds. Flapping one’s hands or pacing the floor puts the stimming person in charge of what their mind thinks about. It can be a way of dealing with stress and anxiety. Sometimes, a stim can just be enjoyable. Finally, there are times when people who stim do it in order to produce sensory input. Maybe their mind needs something to do, so they stim.

Stimming can sometimes be distracting for other students in the classroom. It is best for everyone to understand that this is a completely natural and necessary thing for some people.

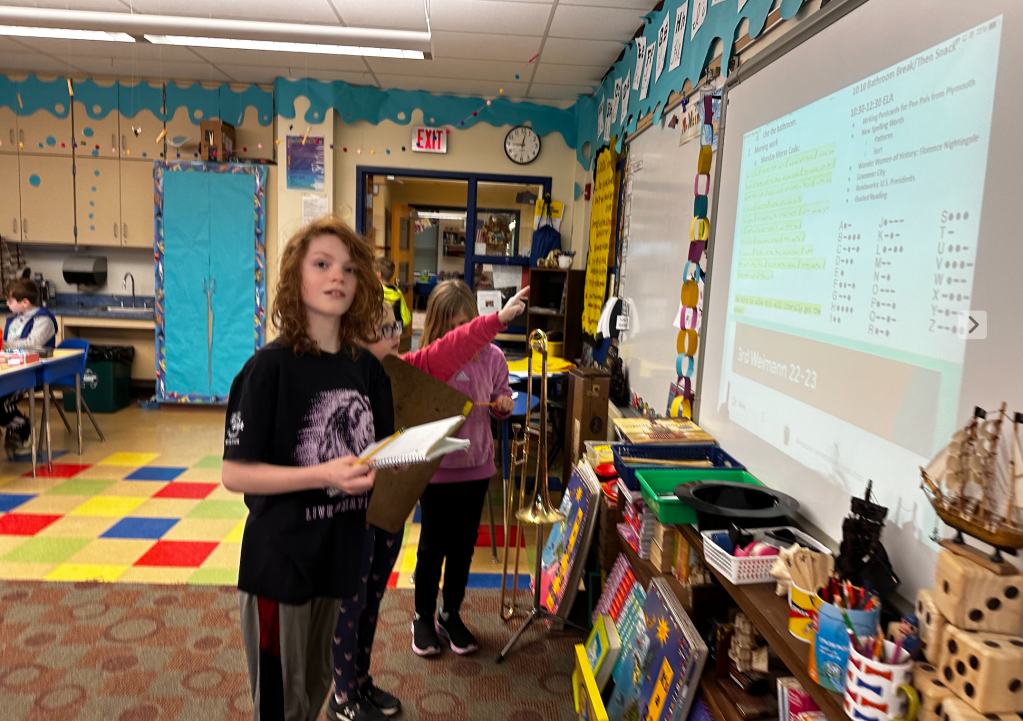

I’ve grown accustomed to my 2nd grade stimmer. When he started talking about quidditch to no one in particular, I just let him pace and say his soliloquy. He was going over the rules for the game, and something he said got me thinking. He mentioned the golden snitch, and said that catching it would win you the game. I didn’t mean to be contrary, but I interrupted his stimming to ask, “Do you automatically win if you catch the snitch?”

He paused his pacing and thought for a moment before explaining, “It is worth 150 points, so whoever catches it will most likely win.” That was a very good answer, but I saw an opportunity for a mini math lesson, that ended up turning into an awesome math lesson!

Another student chimed in, “Catching the snitch ends the match.”

“But does it guarantee a win?” I challenged.

The group thought about it for a second. The quidditch expert conceded that, “No. Catching the golden snitch doesn’t mean you win.”

In order to stretch their thinking and prove my point, I suggested they figure out how many scores the other team would have to make in order to win against a team that caught the snitch. Hardly a second passed before the quidditch expert told me the answer; sixteen.

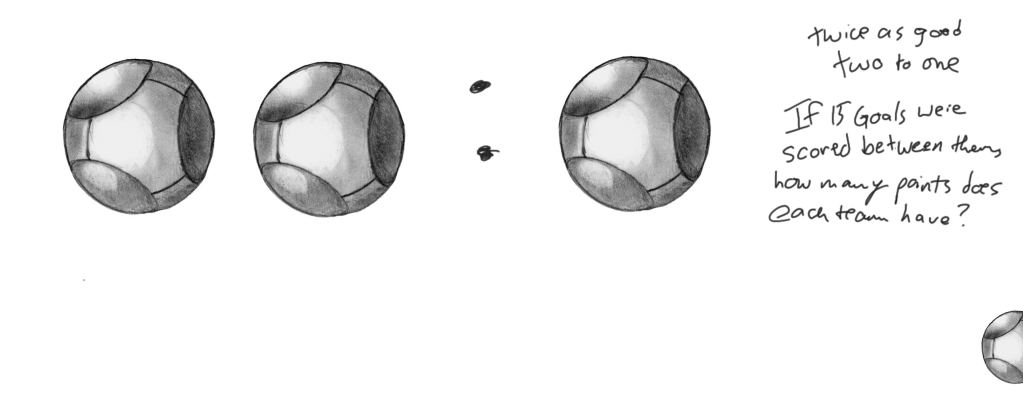

With each score producing ten points, sixteen would mean that the team without the snitch would have ten more points (160) than the snitch-catching team. “But, it is pretty unlikely that one team would score sixteen goals while the other didn’t earn even one,” I suggested. “What if the team that didn’t catch the snitch was twice as good. For every goal the snitch-catchers earned, the other team scored two. Then, how many goals would have to be scored in order to win without catching the snitch?”

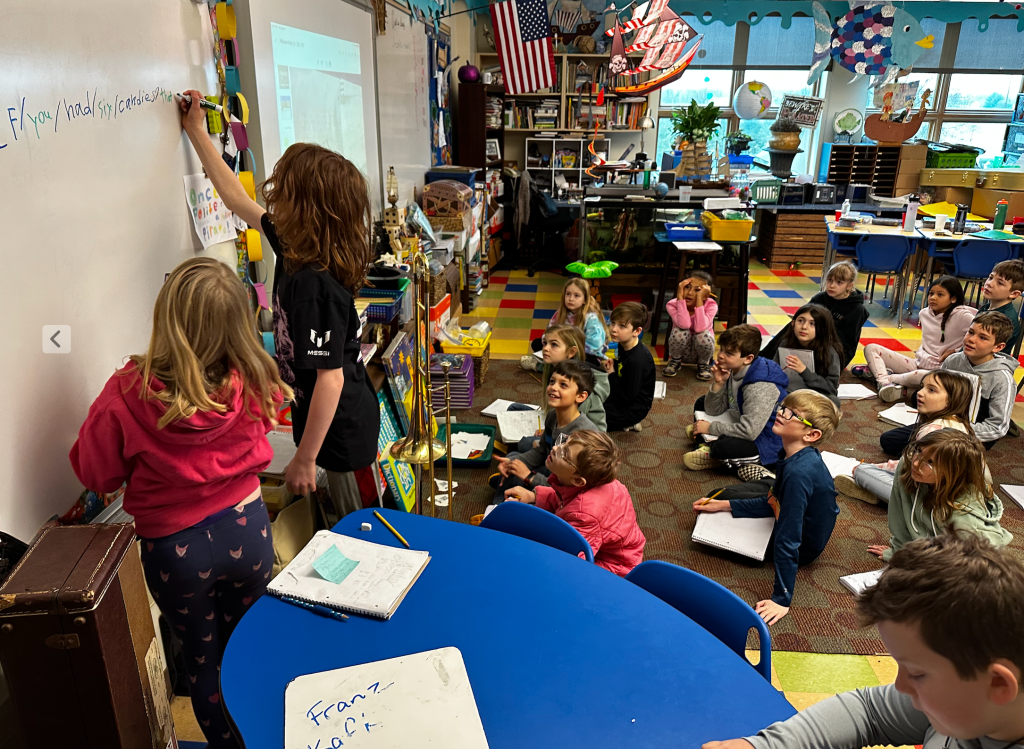

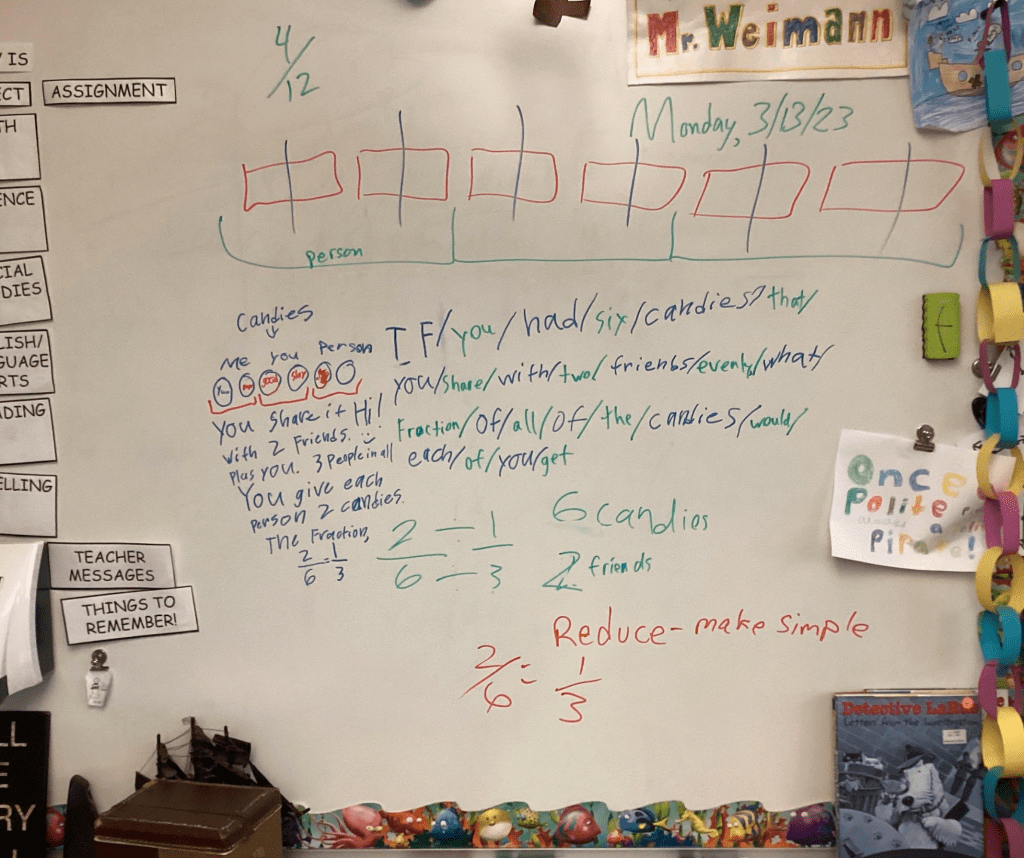

I drew a T chart on the whiteboard. I wrote “Team A” on one side of the T and “Team B” on the other. At the bottom of Team B’s column I wrote 150 and labeled it, “Golden Snitch.” I then wrote a two directly under Team A and a one under Team B. I explained that Team A scored two goals while Team B only scored one. “How many points does each team have?”

When the second graders told me that Team A had twenty points while Team B had ten, I commended them for multiplying the number of scores by ten, the value of each goal. Only, that was not accurate. I pointed to the “150” at the bottom of Team B’s column. “Team B actually has 160 points,” I told them.

I wrote another “two” under Team A and an additional “one” under Team B. “Now how many points does each team have?” At this point it was forty to 170. We kept doing this until Team A’s score crept closer and closer to Team B’s. It took a few minutes to calculate, but my students were riveted to the math. Once Team A earned enough points to overcome the snitch catchers, I restated my original query: “How many goals did Team A need to score inorder to beat the team that caught the snitch?”

They skip-counted to find the answer. I showed them that they could have multiplied the number of twos by two and get the same answer. I also explained to them that the idea of a team being twice as good as another is a ratio. I wrote 2:1 above the T chart. “This means Two to One,” I told them. “For every two goals that this team scored…” I pointed to Team A, “The other earned only one goal.” I left it at that. Our time was up, and they had consumed enough new terms and problem-solving for the morning.

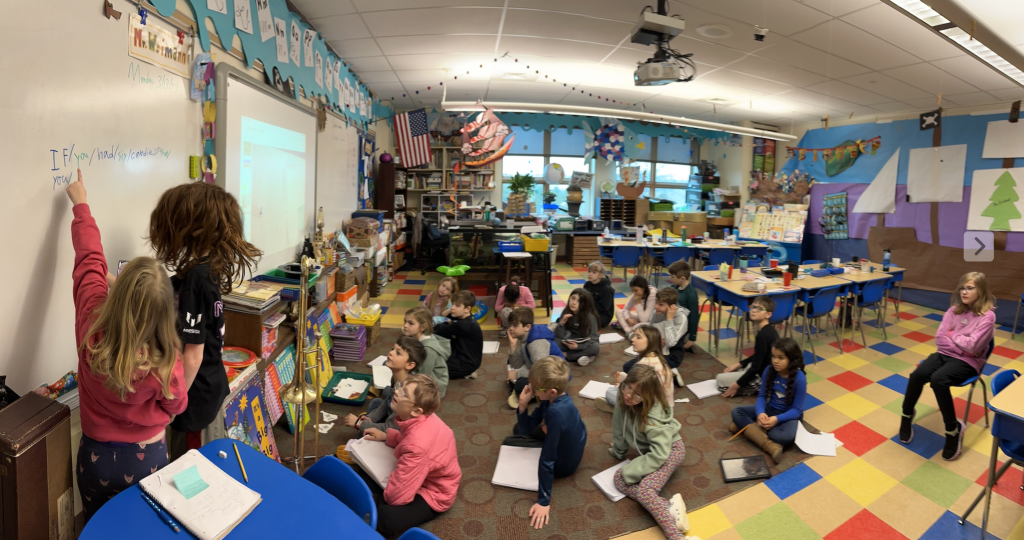

I was so pleased with the spur of the moment lesson that I decided to reuse it when my fourth graders joined me. I wrote the question, along with some quidditch facts, on a Google Jamboard. A couple of fourth graders engaged in drawing on the picture of Harry and writing some random thoughts. I’ve found that letting students do this allows them the freedom to think creatively. This could very well be a form of stimming.

I guided their work by asking the question verbally. I retaught the concept of ratio, which I had introduced earlier in the year. The fourth graders were much faster at figuring out the answer. They immediately guessed thirty goals might push Team A over the edge of victory. I wrote “30” under Team A, and asked how many goals Team B would earn with a ratio of two to one. They accurately told me fifteen. We multiplied both numbers by ten and added the snitch to Team B’s score: Tie.

My students deduced we needed one more score for Team A to have more points than Team B. I told the class that Team B, having a ratio of two to one, could very well score one more goal before catching the snitch. “Just to be safe, we ought to say that Team A should score 32 goals to secure victory over a team that catches the Golden Snitch first when working with a ratio of two to one.”

At this point one of my fourth graders realized that the answer was staring at them from the whiteboard on the other side of the interactive screen on the wall! “Yup,” I conceded. “I worked out this answer with my second graders earlier in the day. We figured it out a different way.” The fourth graders didn’t feel tricked, but just to be sure, I added, “You guys were really fast. It took my second graders and I a while to figure it out.”

“Now, let’s have some fun with ratios,” I told them, as I wrote “3:1” on the board. “What if Team A was three times as successful at scoring quaffles than Team B, but Team B catches the snitch? Now, how many goals need to be scored by Team A to win?”

We started off with thirty goals because it is a nice easy multiple of three and close to our previous answer. If Team A scored thirty goals, Team B would have scored only ten. After multiplying both scores by ten and adding the snitch, we found that Team A didn’t have to score that many goals:

30 * 10 > 10 * 10 + 150 With a difference of fifty (300 – 250 = 50), we figured Team A could have not scored a couple of goals and still have won, even if Team B caught the snitch. We tried again. With 27 goals, Team A would have 270 points and Team B would have scored only 9 goals (using the three to one ratio). Nine goals, at ten points a piece, plus the snitch would mean Team B earned 240 points (9 * 10 + 150). This was closer, but can we do better? Does Team A have to score that many points, or could it be less? Sticking with multiples of three, we gave Team A 24 goals. This would mean Team B would score eight. After calculating the math (24 * 10 = 240 and 8 * 10 + 150 = 230) we saw the difference between the two scores shrink to within one goal.

I took the opportunity to point out the consistency in the scores changing. Team A’s score decreased by thirty with each new calculation, while Team B’s score only went down by ten, but every single time. We explored the idea that 30:10 is the same thing as 3:1. I taught the fourth graders that ratios, like fractions, can be simplified by dividing both sides by the same number. “Ratios explain the relationship between two quantities,” I told them. “The smaller the number the easier to understand how they are related. You don’t say 500 to 100. Five to one is just as accurate and easier to understand.”

Just for fun, I gave my group of fourth graders one more scenario; A more realistic one. I told them that the teams were more evenly matched. I made the ratio three to two (3:2). For every three goals Team A scored, Team B scored two. “Using this new ratio, what is the fewest number of goals Team A would have to score in order to win a match against a team that caught the snitch?”

Because we were still working with thirds, the problem was manageable. It didn’t take my students long to figure out that they could work with numbers that were divisible by three, double the third, and multiply both numbers by ten. We took one of our scenarios from the previous problem, 240 for Team A and 80 for Team B, which represented the three to one ratio, and adjusted Team B’s score to represent the new ratio of three to two. I just erased the 80 and wrote the equivalent of two 80s or 160.

When we found that this new ratio caused Team B to pull away from Team A, students jumped at Team A earning much larger scores. Someone threw out the number 100. I asked them, “What would a third of 100 be?” When no one answered, I restated the question, “What three numbers could be put together to make 100?” Still nothing. I simply told them that it would be 66. I reminded them that a third of one is 0.33. They all sighed with remembrance. They knew that! “When you add some zeros…” I wrote one, and then followed it up with putting a couple zeros behind it. “You move the decimal over. And, since we are talking about a ratio of three to two…” I wrote 66 on the other side of the T chart. After adding 150 for the Golden Snitch, we noticed that the difference was still pretty large.

I showed my students that it was even easier if they began with scores that were divisible by three. From 100 we tried 90. That was simple, but the difference was still too great. Together, we guessed that 81 would be a multiple of three since it is divisible by nine, but how could we figure out the exact number that could go into 81 three times? A tiny bit of long division algorithm did the trick! We did this a couple of times and noticed a pattern. Each time we lowered the dividend by nine, the quotient dropped by three. A really remarkable recognition happened as we figured out the third difference over on our T chart, too. The differences between the two scores were showing signs of a pattern; Each time we shrunk the number of goals that Team A scored by nine, Team B’s final score would drop by exactly 60 points. It went from 810 to 750 to 690 to 630, consecutively! Wow!

The recognition of patterns within the math brought my mind back to what had started this fantastic exploratory math lesson; Stimming. There is something soothing about knowing what number is next. Being able to rely on the consistency of repetition can be comforting. Tapping, singing, pacing, and even skip-counting are all ways to occupy part of the brain, so that other parts may be freed to think. How much stimming a person needs is different for every individual, just like managing it in the classroom environment will differ, but finding just the right ratio can be magical.