Math enrichment, fifth grade style…

This idea came to me several weeks ago, but I hadn’t had a chance to throw it to my fifth grade gifted students until today. The topic that I started with was volume. The fifth graders were learning the algorithm to solve for volume at the time.

I wanted to come up with a reason they would need to discover the dimensions of a 3-dimensional space. My background as a painting contractor came in handy. When I estimated the prices for painting ceilings and walls of rooms, I had to do tons of math. How could I bring that experience into the classroom?

I had the idea of working backwards. I would give them a large number, and they would have to figure out the dimensions of the space.

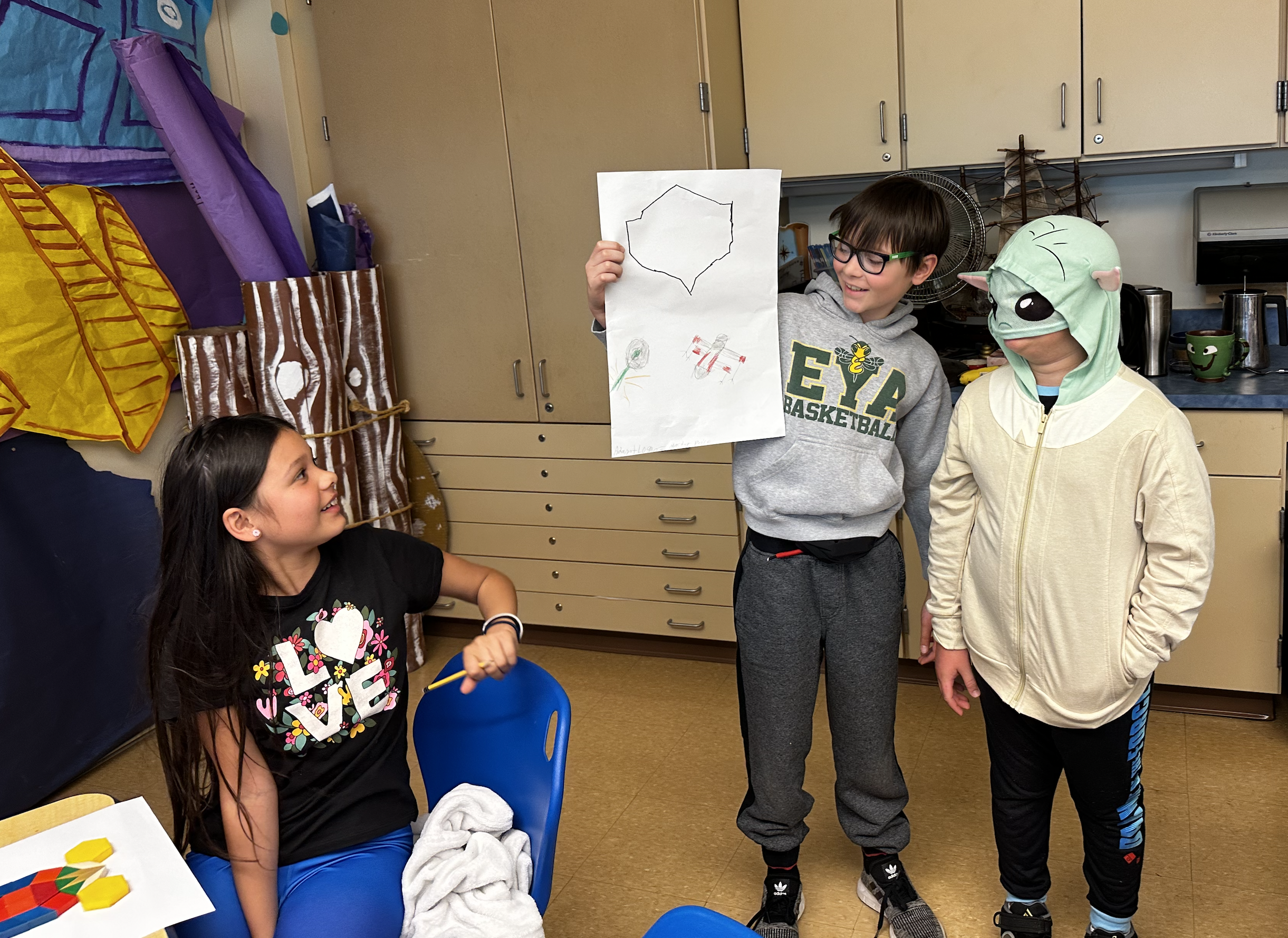

I decided to turn my fifth grade gifted students into interior decorators. They would need to figure out the measurements of floor space and wall surfaces.

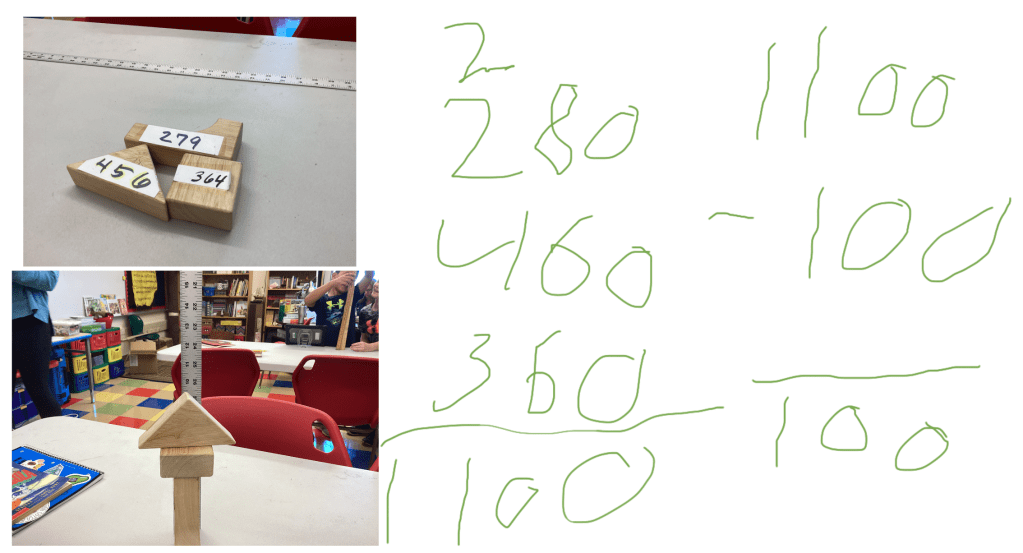

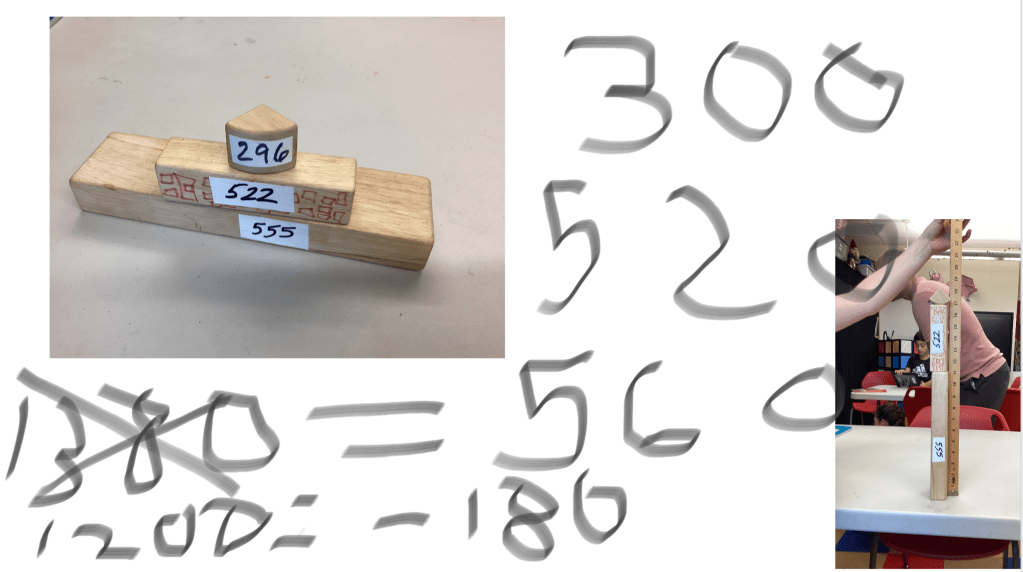

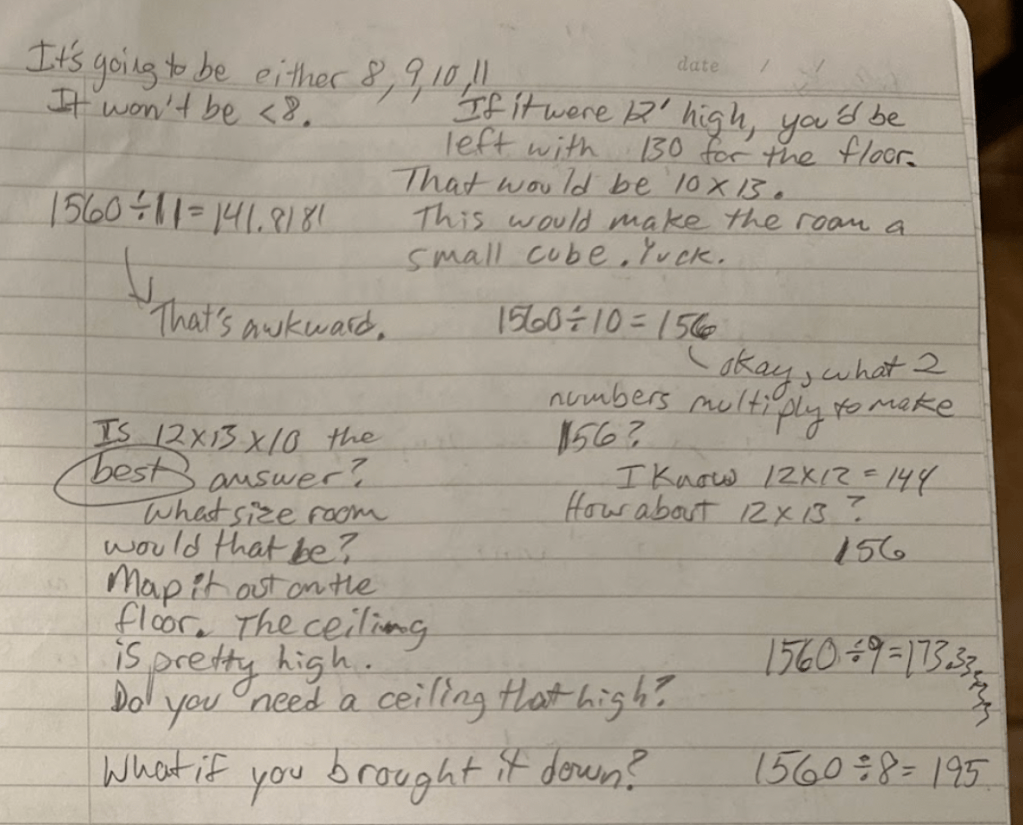

In creating my math problem I tried out a variety of numbers, multiplying length times width times height, until it created a nice round number. I made the ceiling 8 feet high, and the room 13 by 15. That comes to 1560 cubic feet. Before settling on this number, I tried breaking it up various ways. You could do 12 X 10 X 13 for a higher ceiling. This was good, because I wanted there to be more than one correct answer.

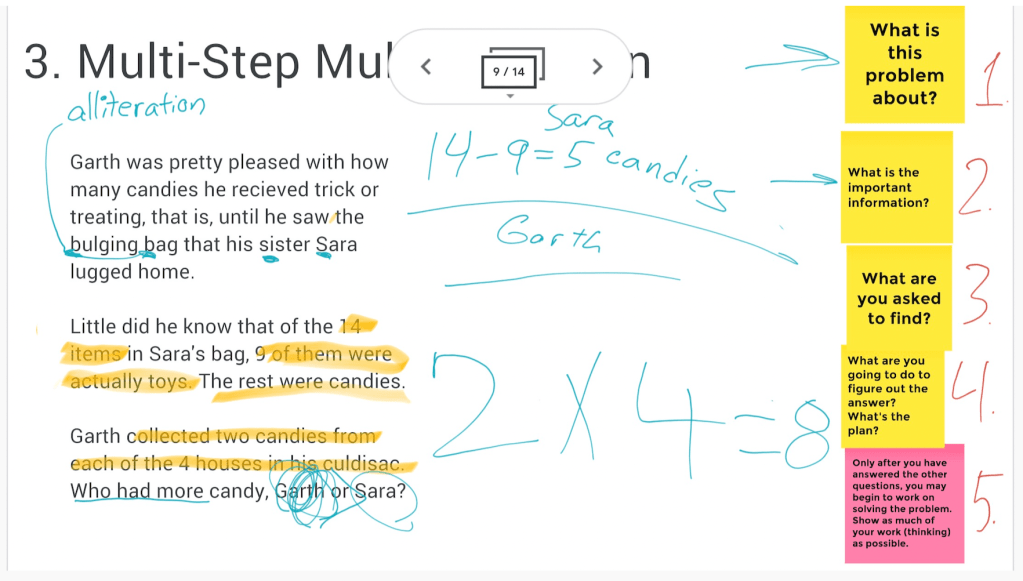

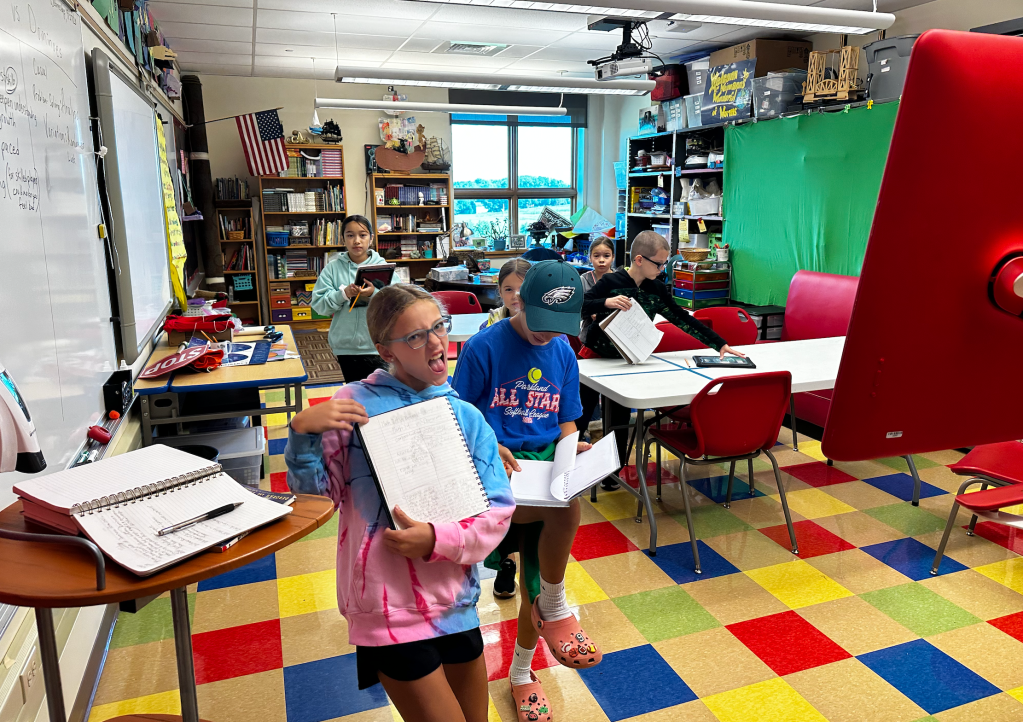

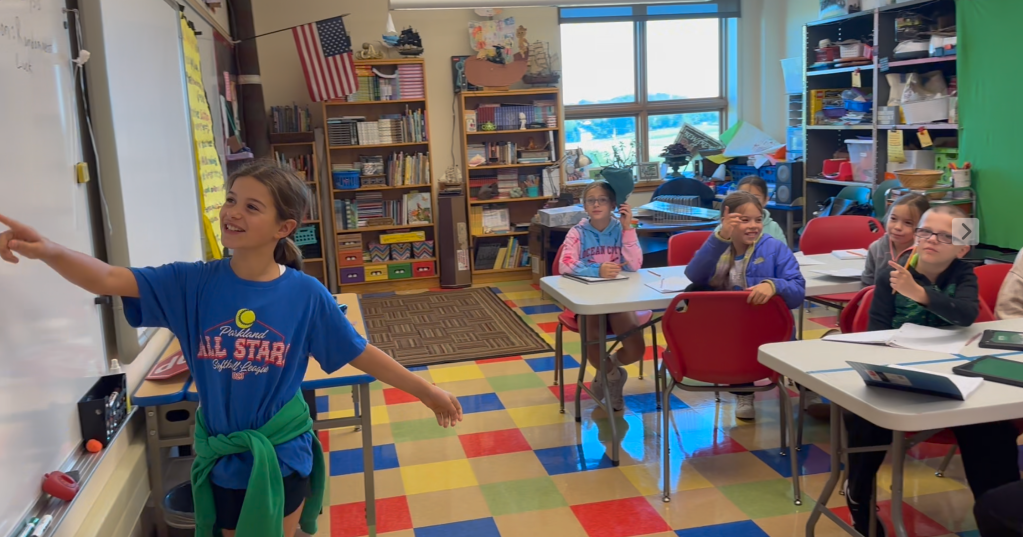

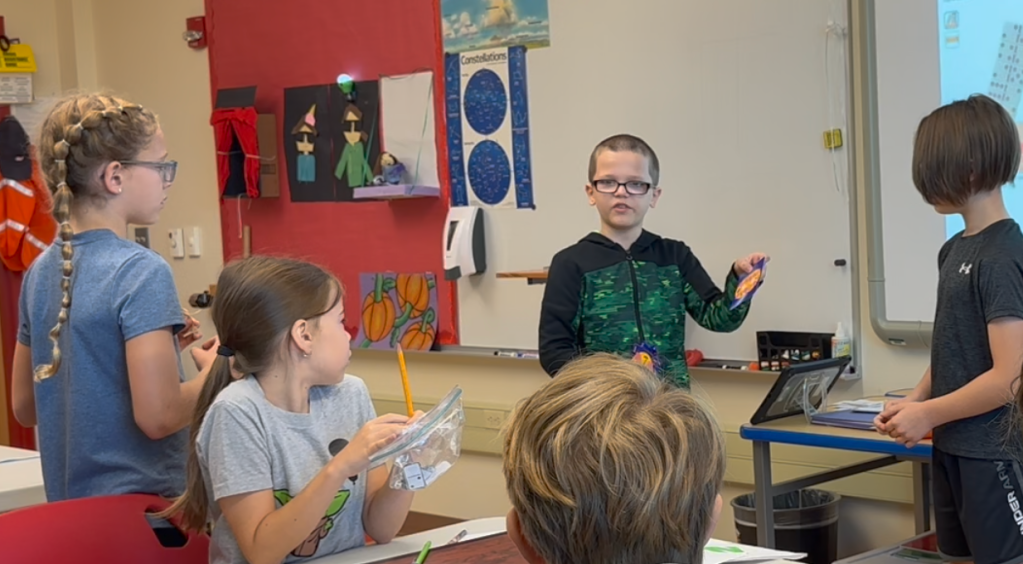

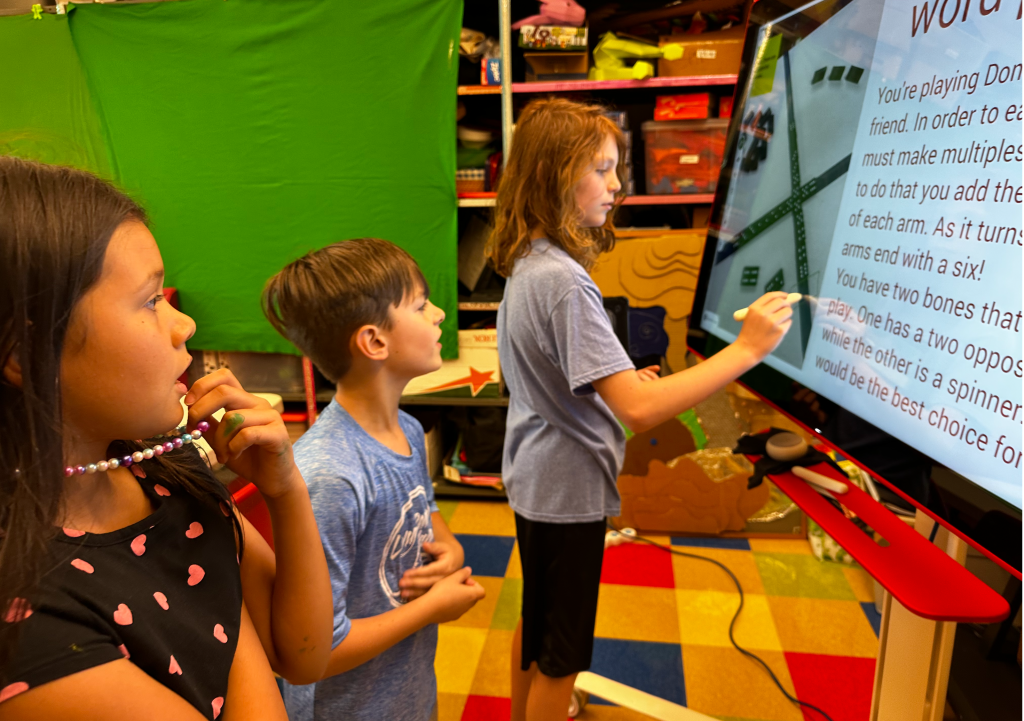

I wrote the problem out and put it on the board for fifth graders to read prior to class beginning. After the announcements, I read the problem aloud to everyone. We practiced our Ready Math routine, the same four-step method I wrote about in a blog about 2nd graders writing their own word problems. First, I asked the fifth graders what the problem was about. Then we discussed what we were asked to find. Next, we identified the information necessary for solving the problem. As it turns out, the only number is 1560, but what does this number represent? And, don’t you know an algorithm that can help you interpret this number? “Yes!”

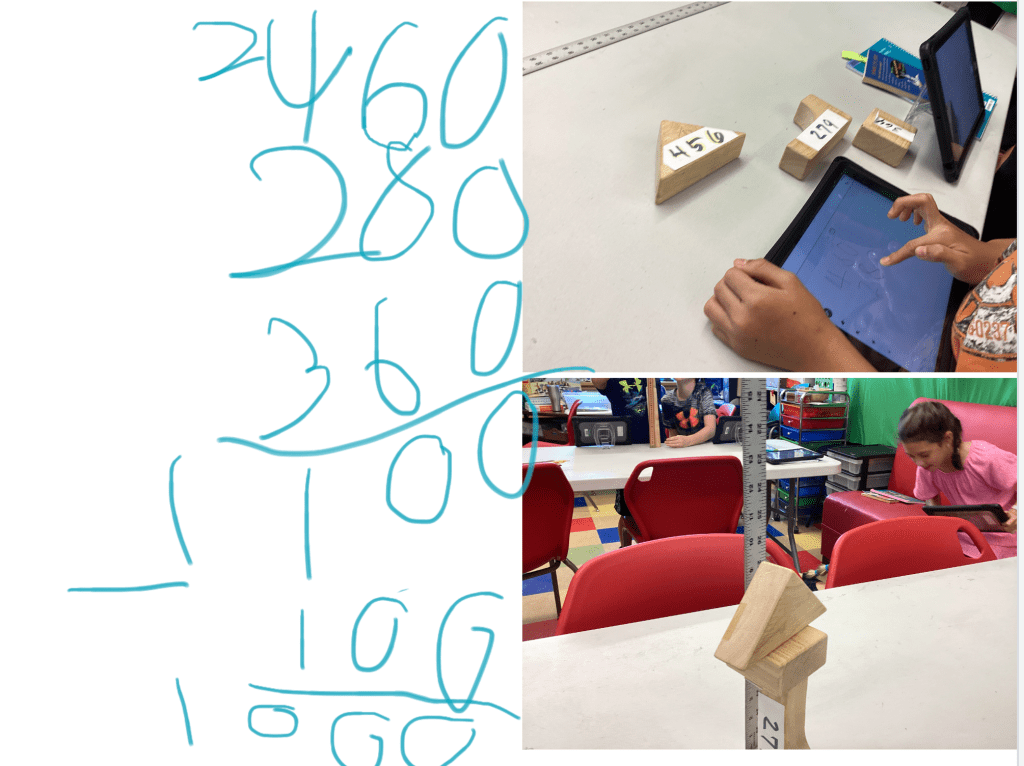

I wrote L X W X H = 1560 on the board, when the fifth graders said it. “So, we identified the topic of the word problem; We know what we have to find; What are you going to do with this number and algorithm?” I guided my fifth graders. “You could try making some predictions. Plug in numbers and see what you come up with,” I suggested when I saw that they needed a nudge.

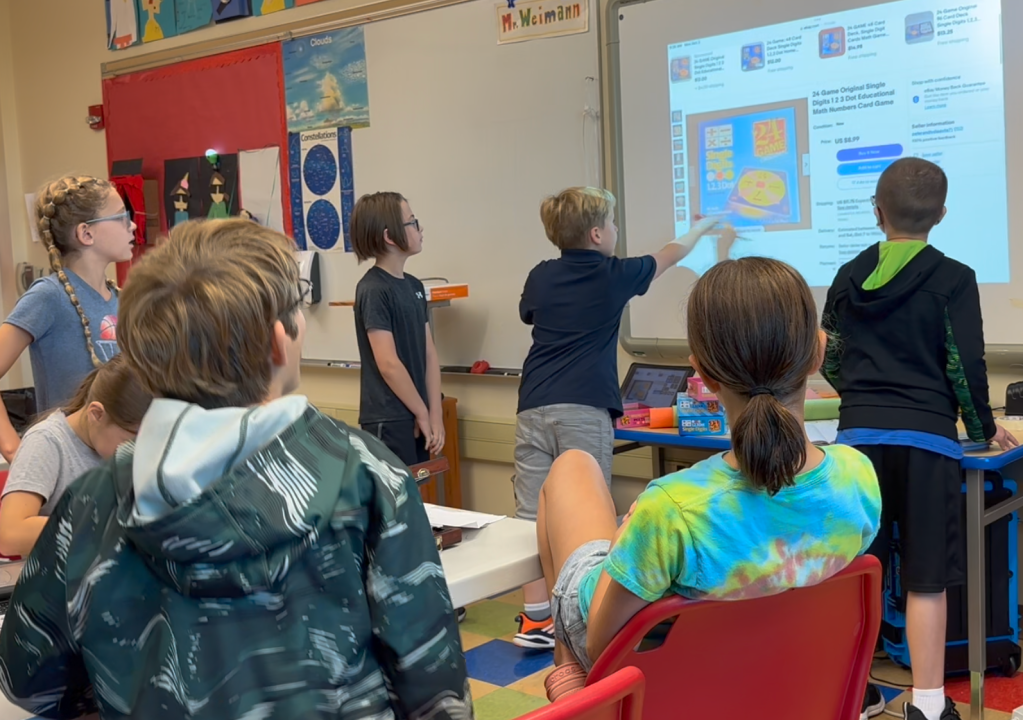

Some students were still stuck, so I asked them what they thought the space looked like. “A cube,” someone suggested aloud. Dylan jumped on deciding the room was not a cube. He used his iPad to find the cubed root of 1560 to be 11.5977, and since one of the parameters was that the dimensions are whole numbers, this option was off the table.

“You can’t use your iPad,” a peer protested.

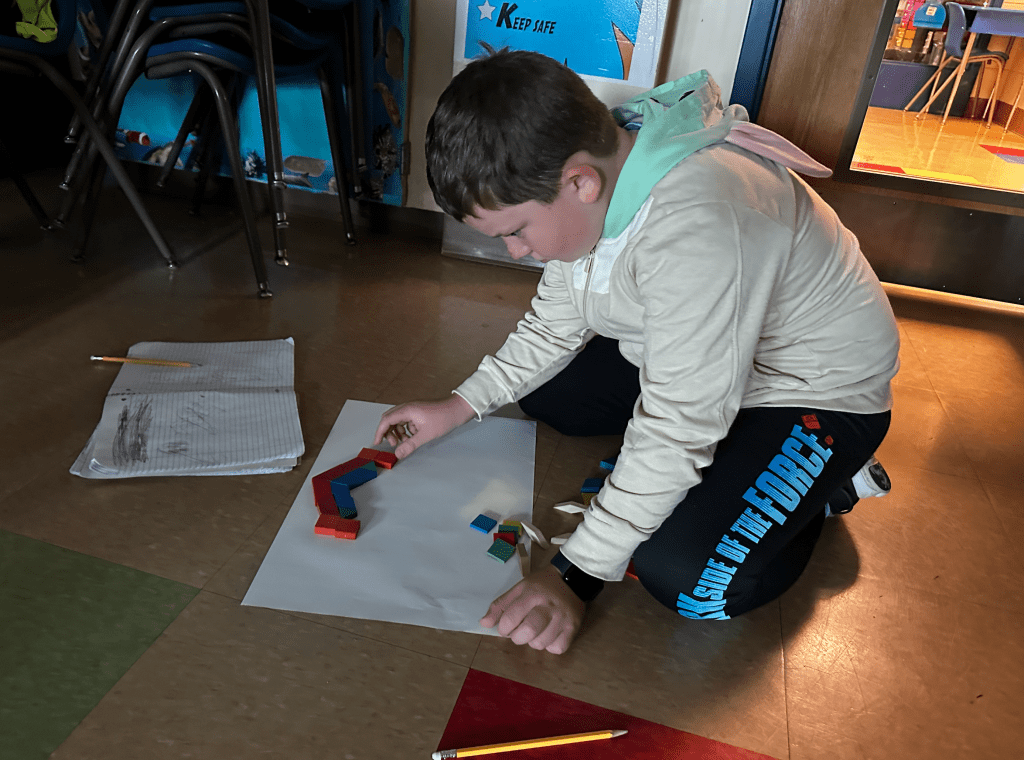

“I never said anything about not being able to use iPads or calculators,” I offered. Fingers feverishly fought to open devices. Not everyone, though. There were some students who chose to stick with paper and pencil.

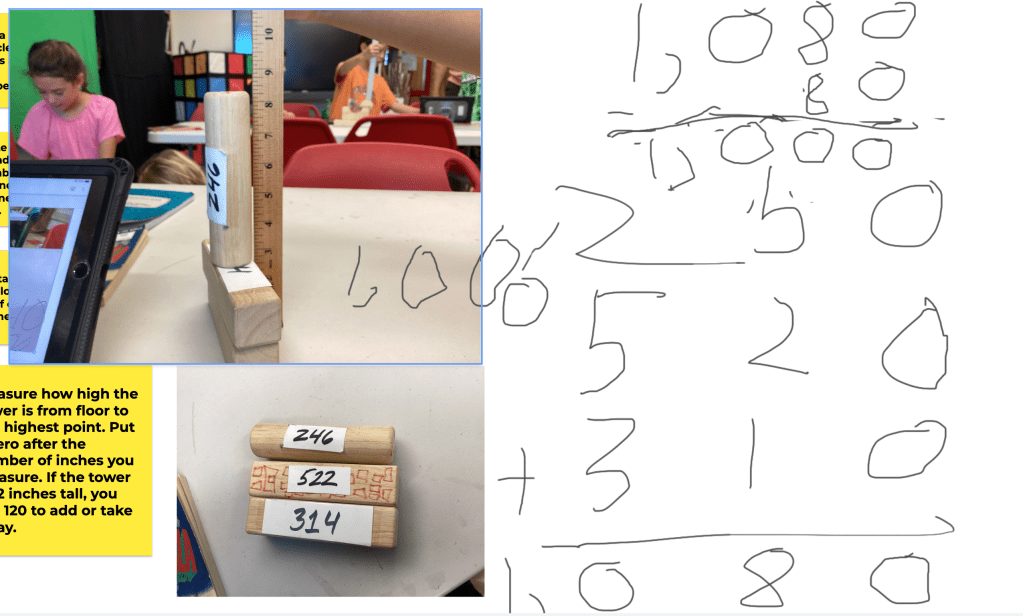

A group of girls asked to use some rulers. When I asked why, they told me that they wanted to get some ideas. This seemed perfect to me. They realized that they needed some background knowledge. They began measuring the classroom.

A student came to me with the dimensions 40 X 39 = 1560. At this point I brought eveyone together for a teaching moment. “If the room were 40 feet by 39 feet, and the volume of the three-dimensional space were 1560 cubic feet, how high would the ceiling be?” They thought about it for a second. Some multiplied 39 times 40 and discovered that it equals 1560. “The ceiling would only be one foot from the floor! Two measurements would make it a two dimensional space. You need a third measurement to give it depth,” I explain. “What could you do with these numbers?”

“2 X 20 X 39,” several students say at the same time.

“So, now we have a two foot high room. This needs to be a space that normal adult humans can walk around and live in.”

“4 X 10 X 39”

“We are getting closer. Why don’t you do to the 39 what you were doing to the 40? Try breaking it up.”

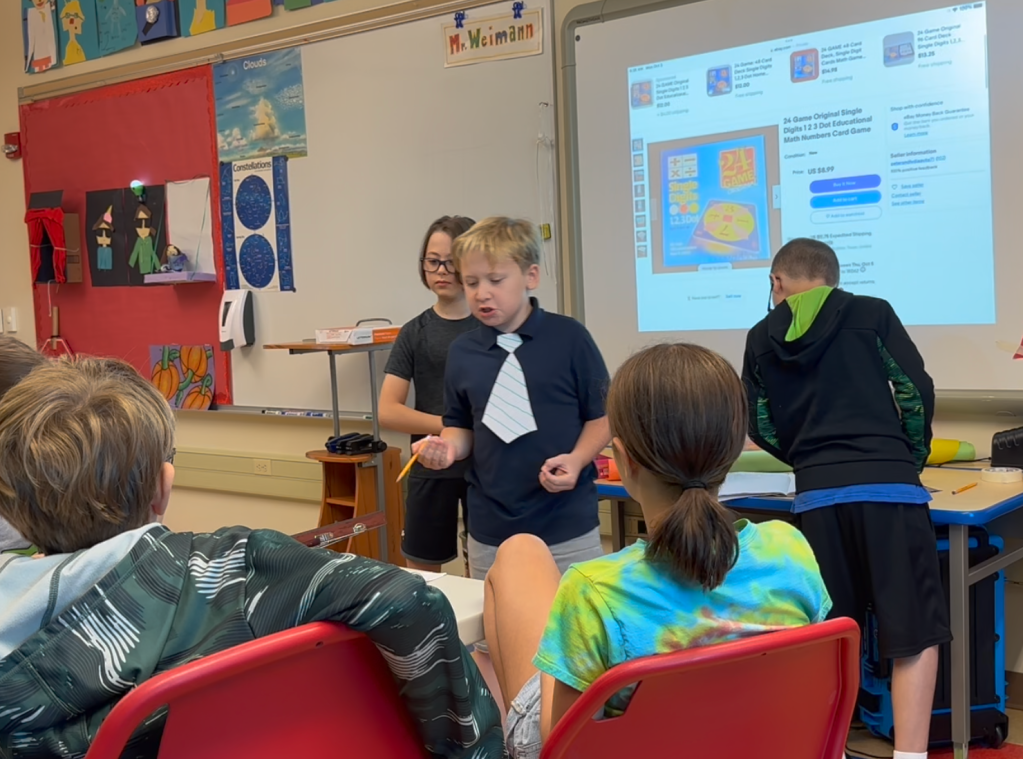

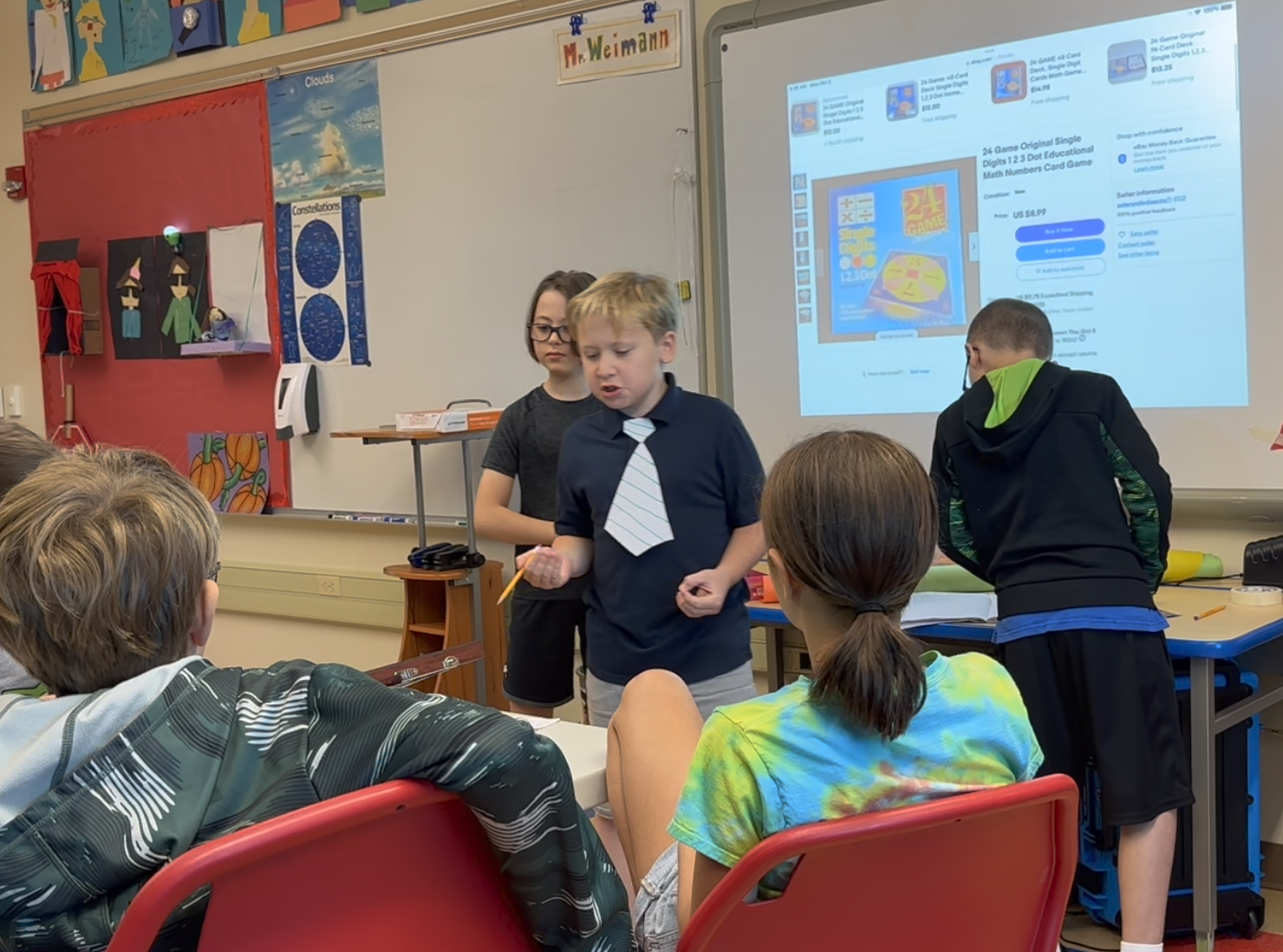

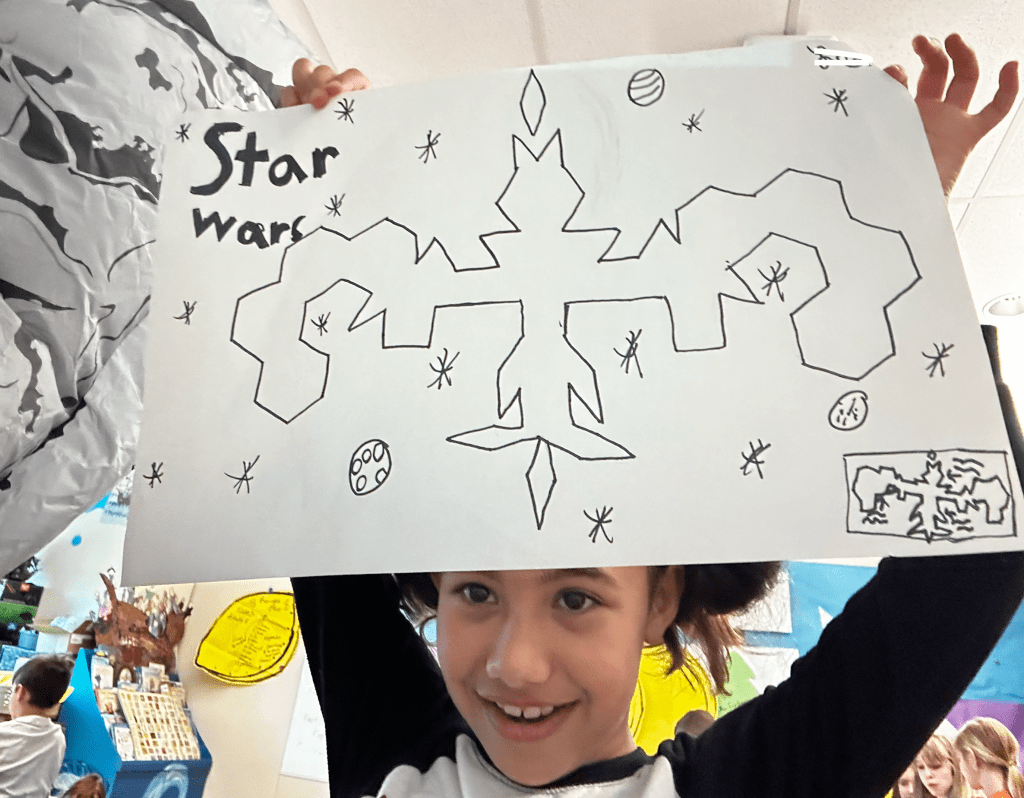

After a while, a few students were beginning to figure out more reasonable dimensions for a living space. They thought that they were done when they came up with three numbers whose product produced 1560, but “Oh, no! You still have to do the interior decorating work. Now that you know the lengths and widths of the walls, you must figure out how much hardwood flooring you need to get. And then, you have to calculate how many double-rolls of wallpaper to order,” I remind them.

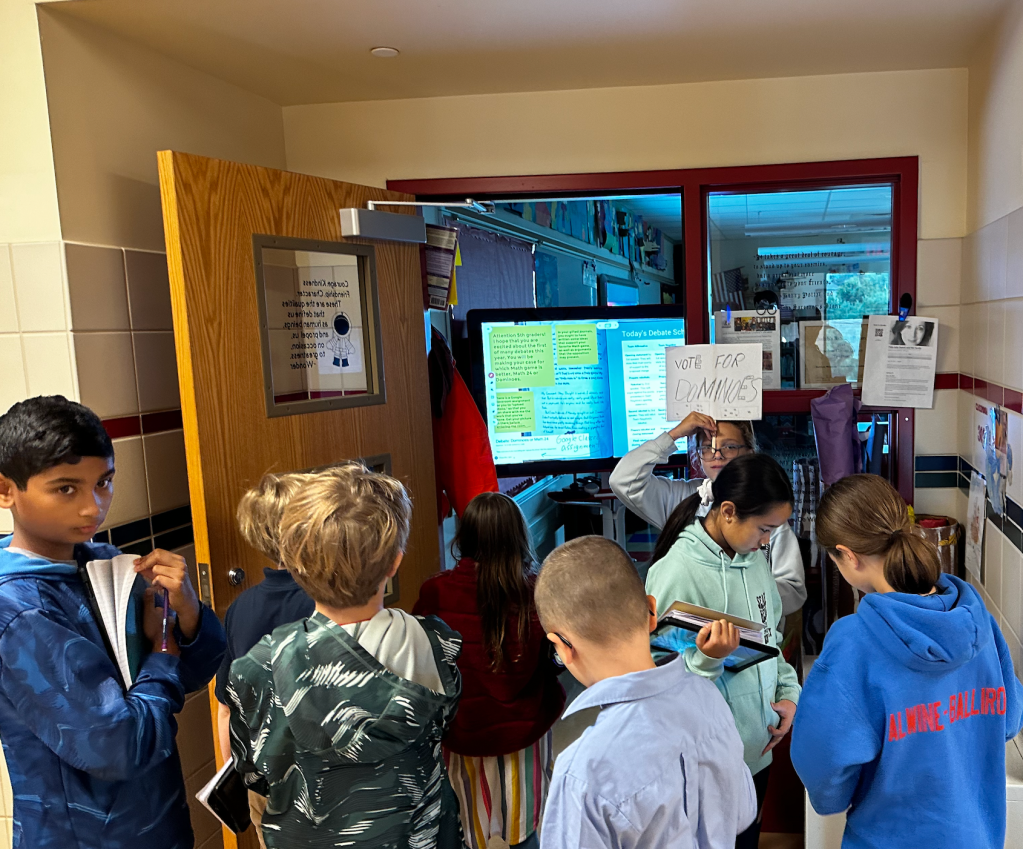

I shared the word problem with the class via a Jamboard, so that they could share their work. They could write right on the Jamboard, or take a picture of their papers, using Jamboard. The classroom was electric with mathematicians calculating, communicating, collaborating. I don’t know about interior decorating, but these students were making my room look and sound great!