Humans love to construct (Lorek, 2018). Is it in our instinct? Sarah Lorek (2018) contrasts the idea that beavers building a dam would be considered “natural” versus humans constructing a dam being “man-made.” The structures look different, and have slightly different purposes, but the reason for construction may not be as disparate as assumed.

[I searched the web for articles that speak to the (my) hypothesis that constructing things might be a human natural instinct and came up short. This would most likely be a very difficult thing to prove, but I’d love to read about it. If anyone knows of any literature or can point me in the direction of a good source, please share.]

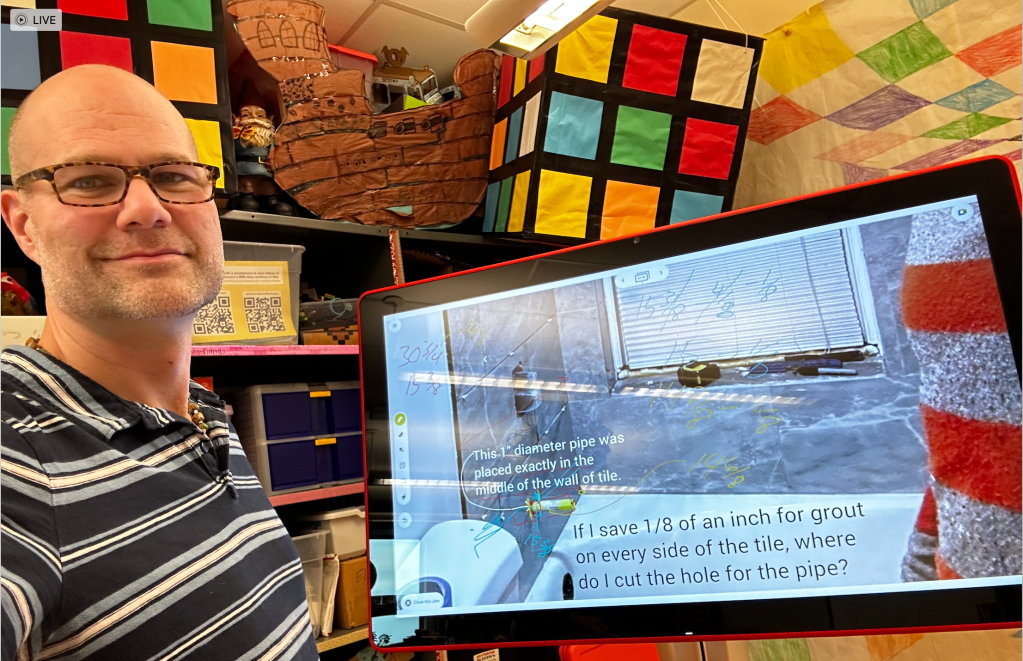

From my own personal experience, I can say that I have witnessed students come to life when building blocks are made available, and some of my favorite activities involve construction. I have fond memories of sitting in the middle of a mess of Legos, Lincoln Logs, and Robotix when I was a kid. I spent hours building spaceships, cities, and robots. Now, I remodel my house (recent bathroom project), labor on landscaping, and generally enjoy working with my hands (famously failed pirate ship project).

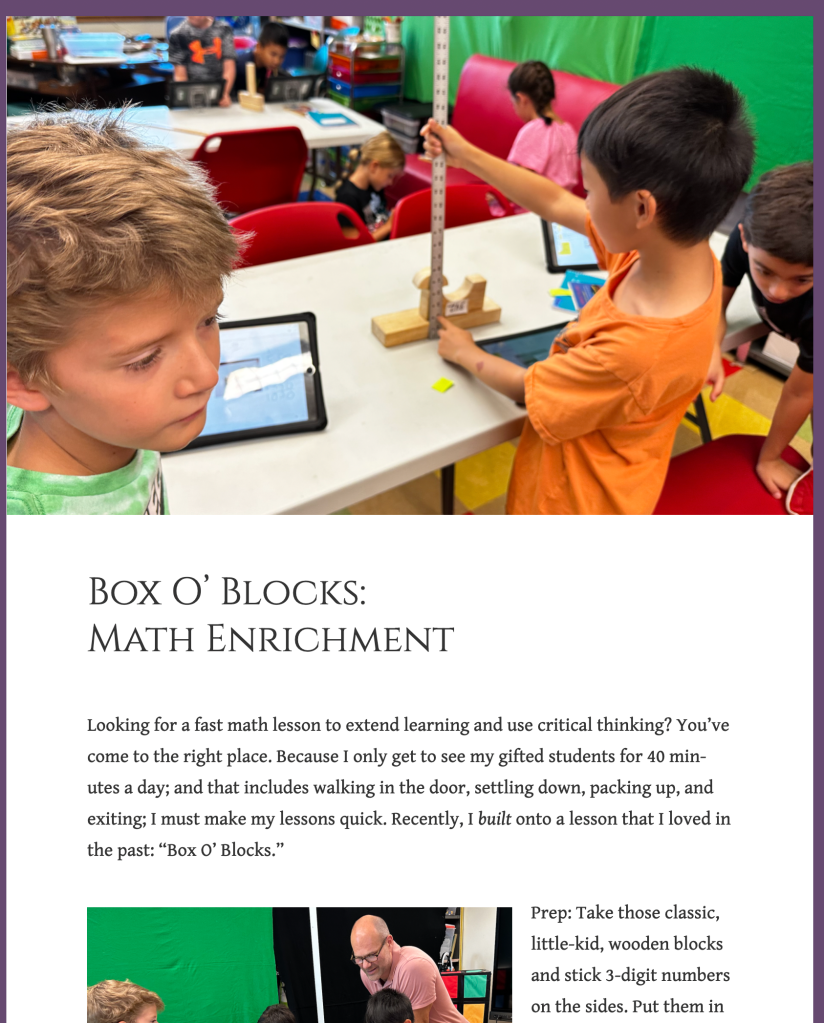

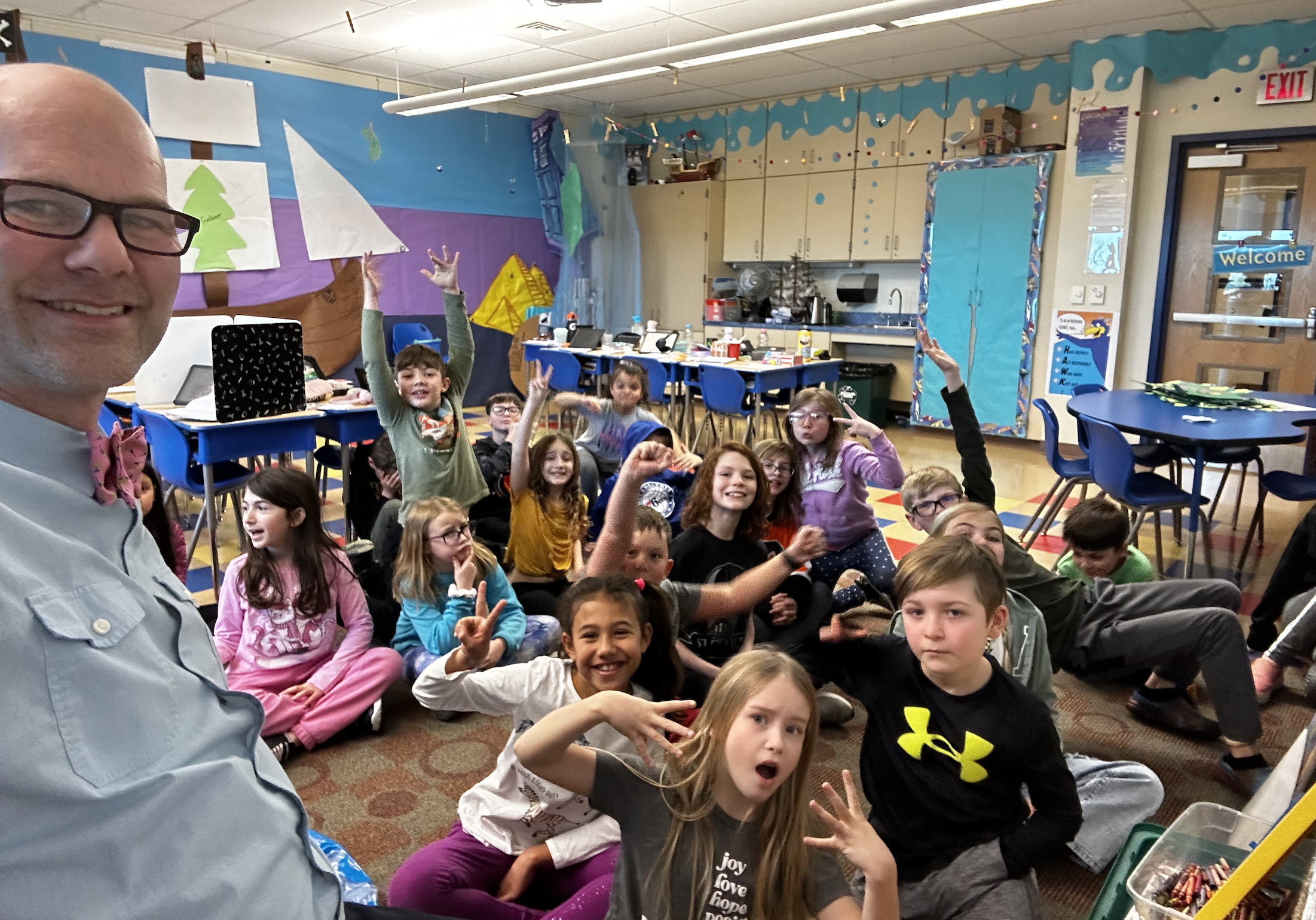

I’ve written about the unique and exciting experience of putting building materials in front of my students. From Building Bridges, using Blocks to teach measurement, Adding Blocks, Purchasing Blocks to use in business plans, constructing Bridges as Object Lessons to teach SEL, and creative Playtime, my students are no strangers to building materials and hands-on lessons. Even during this past lesson, I heard students professing this to be the best Math Enrichment lesson, yet!

Purpose

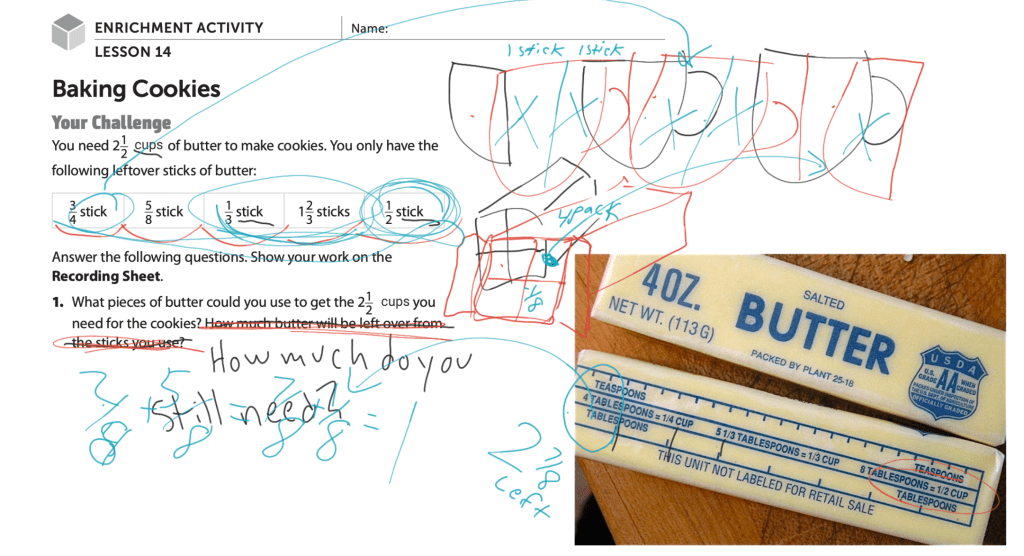

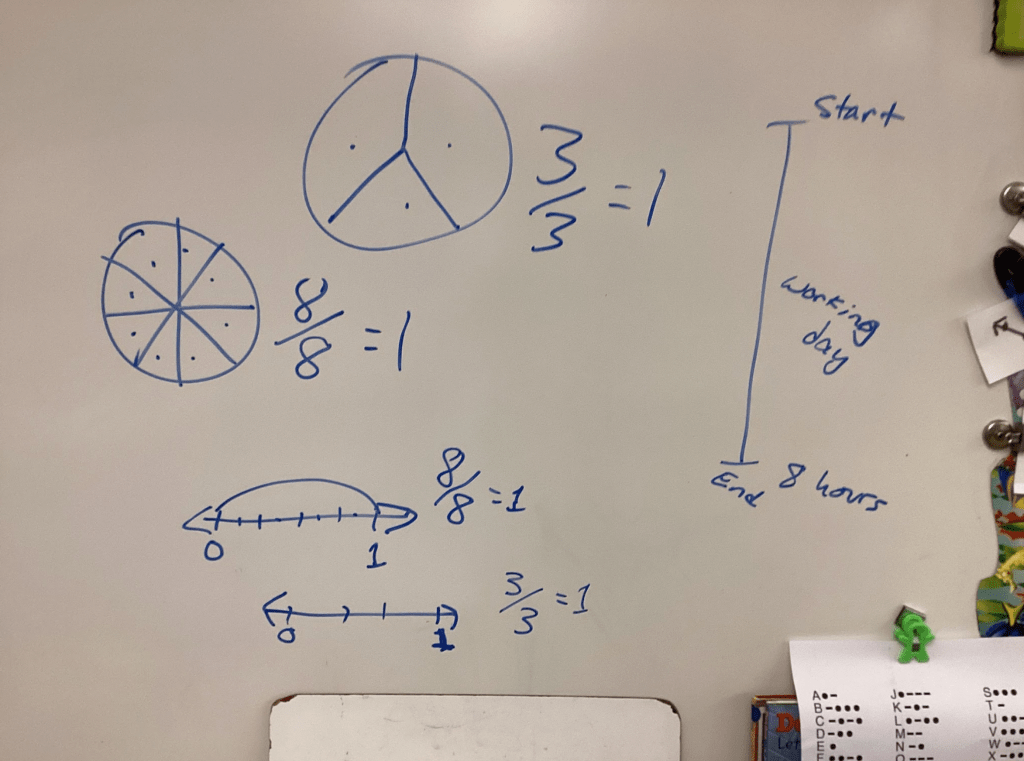

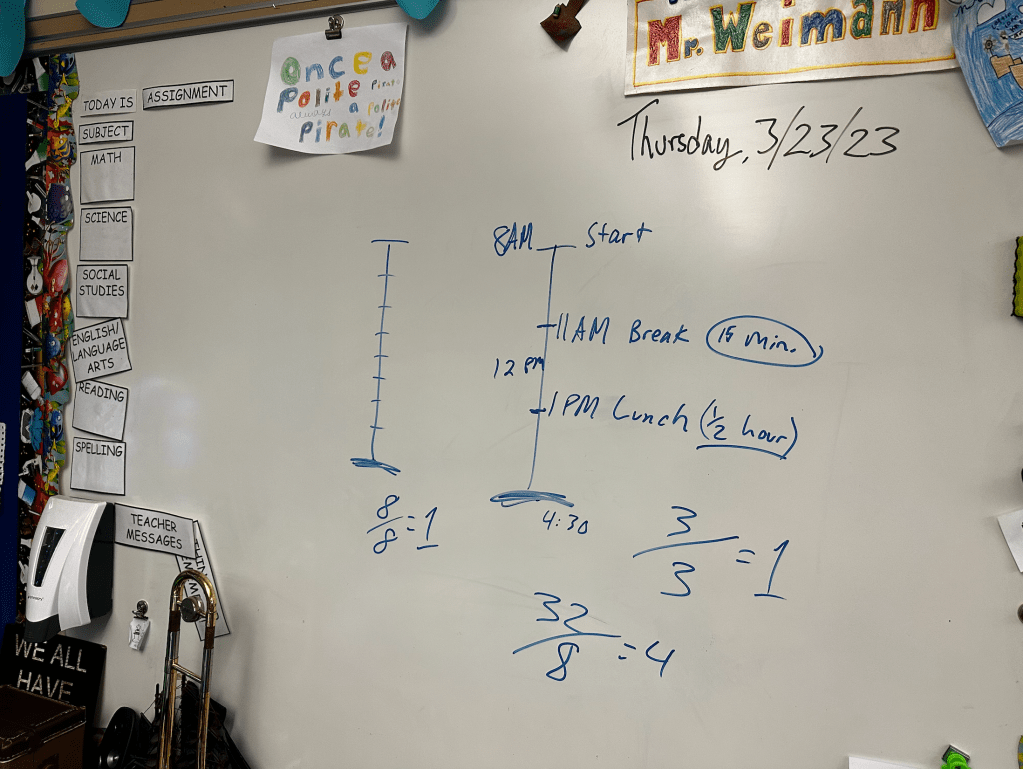

Students have been introduced to fractions in their regular math classes. I was planning to enrich a lesson about comparing fractions. Our math curriculum had a nice worksheet that would have students create quilts with limited colored squares, and then compare the fraction of each color. Students can still do that lesson, but independently in the classroom. I created a lesson that was hands-on and interactive.

Students would use colorful connecting blocks to construct an arch. I had a picture of the arch in Washington Square, NYC on the board when they entered the room. We discussed the idea of arches for a few seconds before I shared the parameters of the project.

Arches are symbolic, letting in light and allowing people to walk through walls. They are old; developed during the second century B.C. They are also timeless, in that they are still used today. They have even been known to hold magical properties! Vampires must receive permission or an invitation before entering someone’s home (through an arch), and the arch makes an appearance in Harry Potter as a passageway between this life and the beyond.

A memory that popped into my head that will definitely date me is that of the movie “Ernest Goes to Camp” (1987). The image on the cover of the movie shows the arch that Ernest is working on at the very beginning of the movie, surrounded by several scenes from the flick.

Parameters

As per a recent lesson that I learned about setting tight parameters, I constructed very strict limits on student creations. Students were allowed exactly 24 cubes. I chose this number because we have been learning and playing Math 24 a lot recently, and because the number 24 is divisible by many numbers. The lesson could include reducing fractions, making common denominators, and more through starting with 24 for a denominator.

The blocks could only be red, green, blue, and/or yellow. At least three different colors were to be used. This ensured that there would be some comparisons between fractions.

Students could work independently or with a partner, but no groups larger than two. Each student, whether working with a partner or alone, would be responsible for putting information about their project into a Google classroom assignment.

Activity

Once the assignment was explained, I set them loose. They were busy bees, buzzing around the blocks, loving the building. Creativity bubbled in the classroom. There was a purposefully leaning arch, decorative arches, symmetrical aches, one was made as short as possible while still fulfilling the definition of “arch,” and one even mimicked the pointed style of the Gothic Arch. So impressive!

I stopped the students when some of the first arches were being completed, so that I could instruct them on what to do next. I had a couple of girls hold up their arch for an example. We took a photo of it, which is what I wanted everyone to do. This way, I could assess the accuracy of the numbers. It demonstrated to students that they must provide evidence.

Next, we counted the number of different colored blocks. The girls had made their arch symmetrical and used the same number of colors for each of the three colors. (This is something I fixed the next time I taught the lesson, that afternoon; “None of the colors can be the same number.”)

I showed the students how to write the fractions next to the color of blocks that I had provided for them in the software that they were manipulating. Then, we wrote an equal sign between the two fractions. The way I got the girls to include “greater than” and “less than” in their project was by combining colors. “The fraction of cool color blocks was greater than the fraction of warm color blocks.”

Time was allotted for producing fractions and making comparisons on iPads. In order to do even more comparing of fractions, I then had students take pictures of a neighboring team’s arch. They then imported that photo into their Google Jamboard project so that both their arch and their neighbor’s arch were side by side on a slide. Now, they got to compare the fraction of red blocks from their arch with the fraction of the other arch that was constructed with red blocks. This exercise involved talking about the math, sharing out, and self assessing.

In the end, students enjoyed not only comparing fractions, but constructing them, building knowledge, and cementing learning into a fun and memorable experience.

Sources

Azzarito, A. (2021, August 19). From Architectural to Artistic, Arches Are Trending. SemiStories. https://semistories.semihandmade.com/design-history-arches/

Lorek, S. (2018). Ancient Architecture and the Human Need to Construct. Trimble Construction. https://constructible.trimble.com/construction-industry/ancient-architecture-and-the-human-need-to-construct

Sinclair, L. (2014, December 19). The History of Architecture in Eleven Arches. The Architectural Review. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/the-history-of-architecture-in-eleven-arches

The Top 10 Construction Toys of All Time. Michigan Construction. (2017, December). https://blog.michiganconstruction.com/the-top-10-construction-toys-of-all-time

Over the weekend I finally experienced “Teach Like a Pirate”. I listened to the recently produced (Jan. 2019) audio book, read by the author,

Over the weekend I finally experienced “Teach Like a Pirate”. I listened to the recently produced (Jan. 2019) audio book, read by the author,

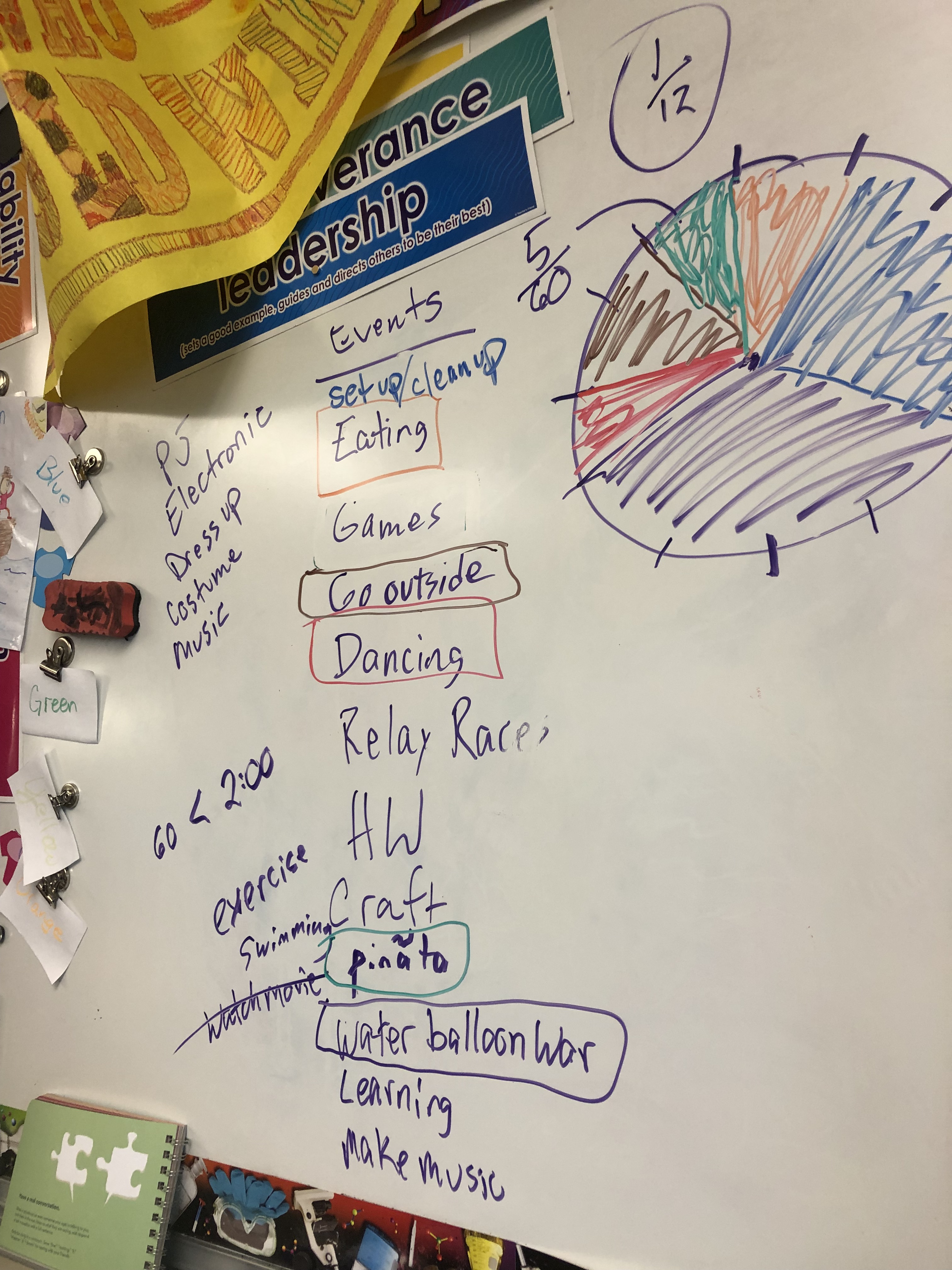

During the brainstorming time I was building rapport. Not between myself and the students–that happened in September, and I had plenty of it–but between my students and the subject matter. Remember, I am teaching them math through all of this! The way I see brainstorming, it is like student ability: Every kid can do the math, some faster, some easier, some needing patience, help, and additional explaining. In my brainstorming sessions, every idea is acceptable. This makes it fun and funny, also. When a kid suggests a water event, I say, “Did you just say No-holds-bar-water-balloon-war!?” The classroom erupted… and the ideas poured in like the water filling those metaphorical balloons. Just as a teacher needs to redirect thought to shape learning, I rephrased student ideas to write a list of potential party events on the whiteboard.

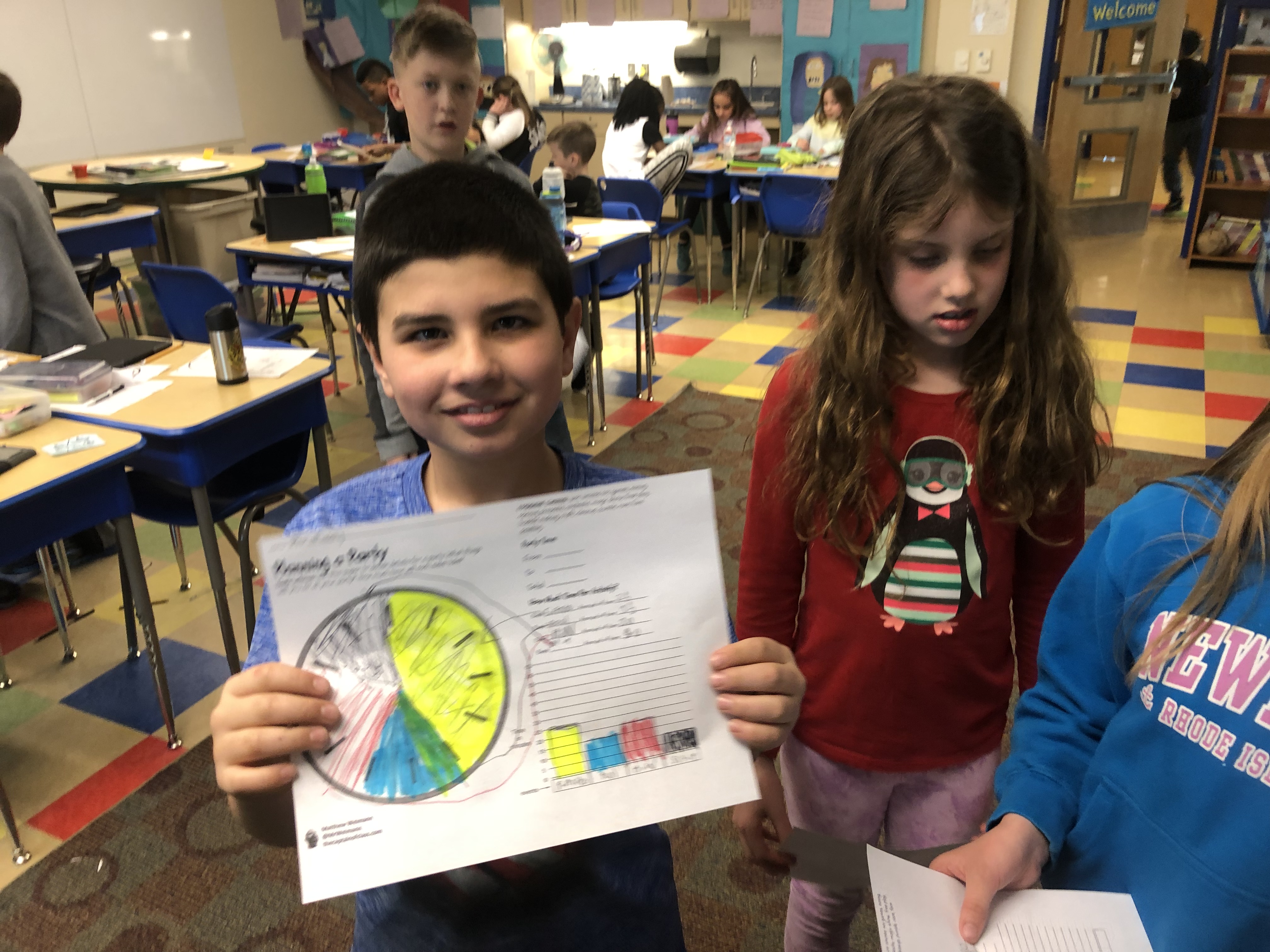

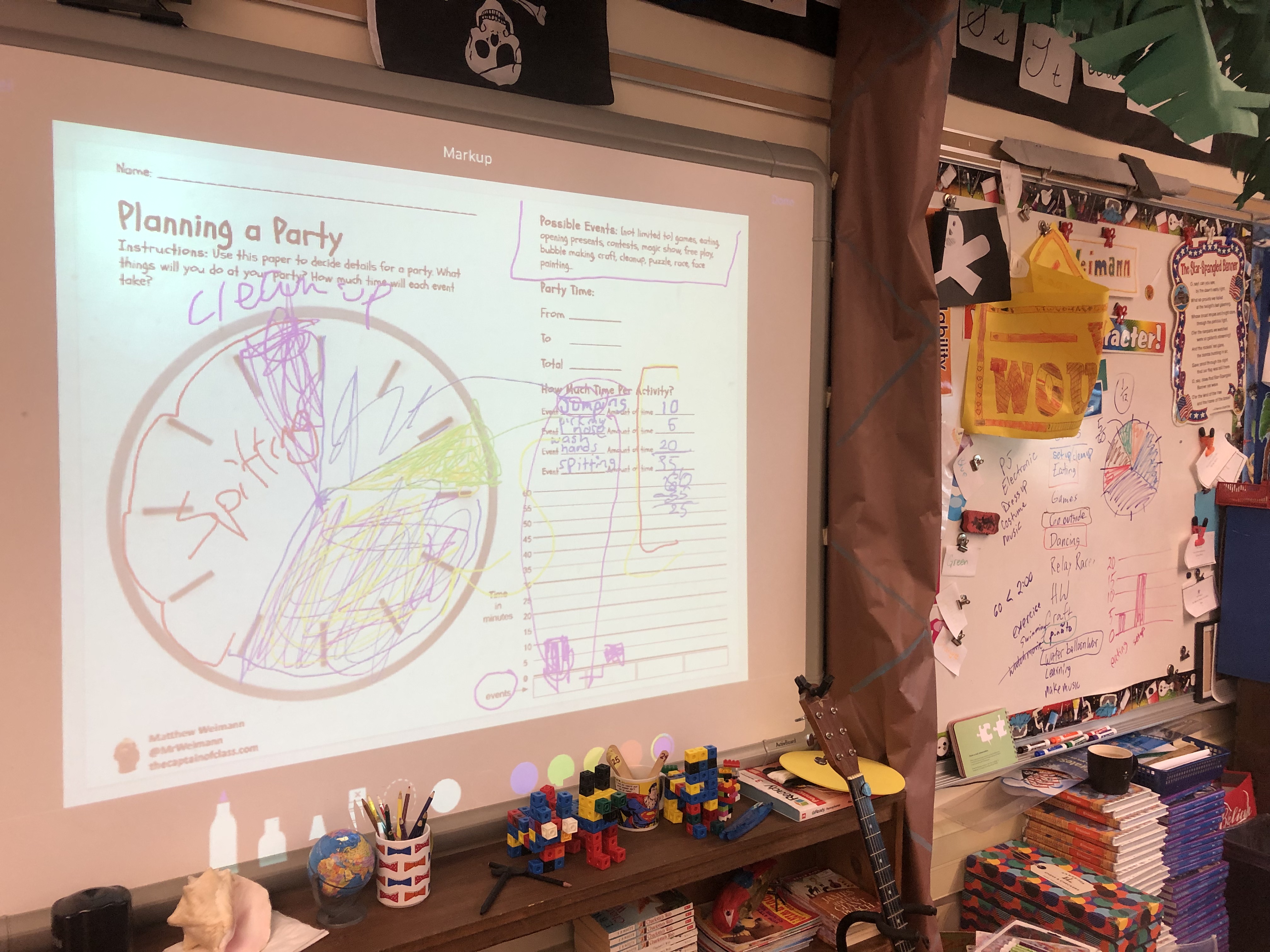

During the brainstorming time I was building rapport. Not between myself and the students–that happened in September, and I had plenty of it–but between my students and the subject matter. Remember, I am teaching them math through all of this! The way I see brainstorming, it is like student ability: Every kid can do the math, some faster, some easier, some needing patience, help, and additional explaining. In my brainstorming sessions, every idea is acceptable. This makes it fun and funny, also. When a kid suggests a water event, I say, “Did you just say No-holds-bar-water-balloon-war!?” The classroom erupted… and the ideas poured in like the water filling those metaphorical balloons. Just as a teacher needs to redirect thought to shape learning, I rephrased student ideas to write a list of potential party events on the whiteboard.  Finally, it was their turn. I showed the class the graphic organizer that I had made for them. They gasped when they saw that it was exactly like what we had just made. Because I presented it screen mirroring my iPad, I could quickly draw all over it. I showed them how they would plan events, fill in the pie graph, and make a bar graph. I told them that they weren’t allowed to use the same exact ideas that we had come up with together. They could have “eating”, but not the same amount of time. In other words, don’t copy, create. They were all cool with that. I stimulated this by writing crazy ideas on the graphic shown on the board: “Picking nose for 5 minutes, followed by washing hands for 20 minutes… because that was gross!” They loved it.

Finally, it was their turn. I showed the class the graphic organizer that I had made for them. They gasped when they saw that it was exactly like what we had just made. Because I presented it screen mirroring my iPad, I could quickly draw all over it. I showed them how they would plan events, fill in the pie graph, and make a bar graph. I told them that they weren’t allowed to use the same exact ideas that we had come up with together. They could have “eating”, but not the same amount of time. In other words, don’t copy, create. They were all cool with that. I stimulated this by writing crazy ideas on the graphic shown on the board: “Picking nose for 5 minutes, followed by washing hands for 20 minutes… because that was gross!” They loved it.