My 5th grade gifted class revisited the game of Dominoes last week. It took some review, but they enjoyed playing the game. I told them that one of the reasons I had taught them the game was because it is a classic that they could play with grandparents and other elderly people, bridging the gap between generations. The game has been in existence for over 900 years!

In addition to the game being old, it also presents an opportunity to practice strategic thinking. In an effort to prove this to my 5th graders, I have begun dreaming up scenarios where a player might use analytic skills to make a counter-intuitive move that would benefit them in the long run.

There are times during a game when you have more than one Bone (Domino) that you can play, but none of the plays will give you points. Sometimes, it does not matter which one you put down, but other times you can plan ahead. Much like you would in chess, you can set up future moves by arranging the Bones to meet your needs. Playing them in a particular order would benefit you more.

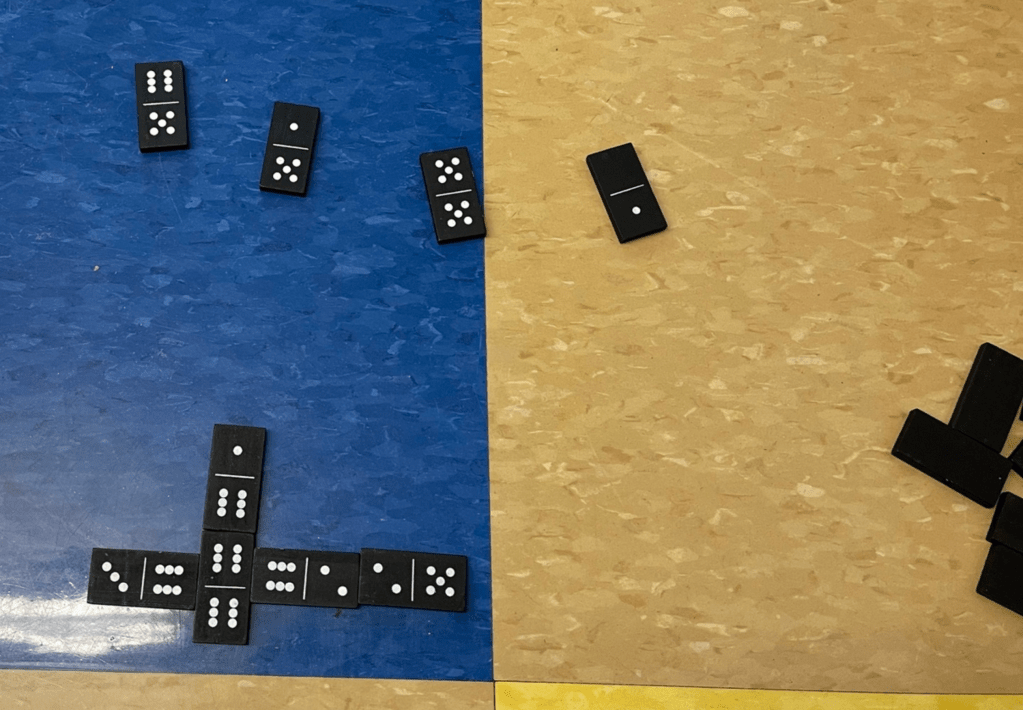

I planned on showing my 5th graders what I meant by setting up scenarios of games and taking pictures. I have done that many times to teach the problem-solving aspect of Dominoes.

Then I thought, Why not have my gifted students make up the puzzles themselves? I will give them the parameters, and they have to try to figure out how to show the need for strategic thinking through constructing an image of a hypothetical game.

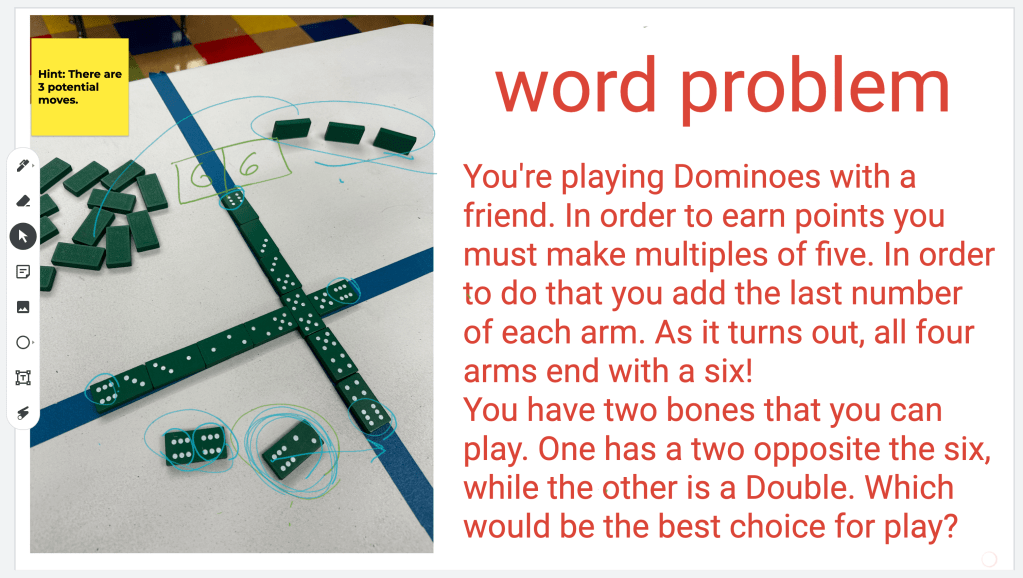

The puzzle would be an image showing Bones (Dominoes) already played, Bones available to a player (standing up so Pips or dots were showing), blank sides of the opponent’s Bones, and maybe a Boneyard (unused Dominoes).

If you are a novice Dominoes player, some of this vocabulary might be new to you. Bones are the game pieces, named after what they were originally made out of; Ivory or elephant tusks (bones). The Boneyard is made up of the unused Bones lying face down. Face down means that the Pips or dots on the bones are not showing. All you can see is a blank Bone or the uniform design that is printed/carved on every one of the 28 Bones of the set. Bones often have something decorative on the side without Pips, so that players can identify the 0-0 Bone more easily. Every Bone has two numbers on it. There are two ends of the number side of a Bone. No two Bones have the same combination of numbers. Beginning at 0-0, the Bones go up to 6-6.

The Plan: In order to demonstrate strategies for play, I am going to have my 5th graders come up with puzzles that point to weighted plays. In other words there will be better moves than others. People trying to solve the puzzles will have to analyze the potential moves. Which one is better and why? Puzzle-solvers will be required to explain the move they chose.

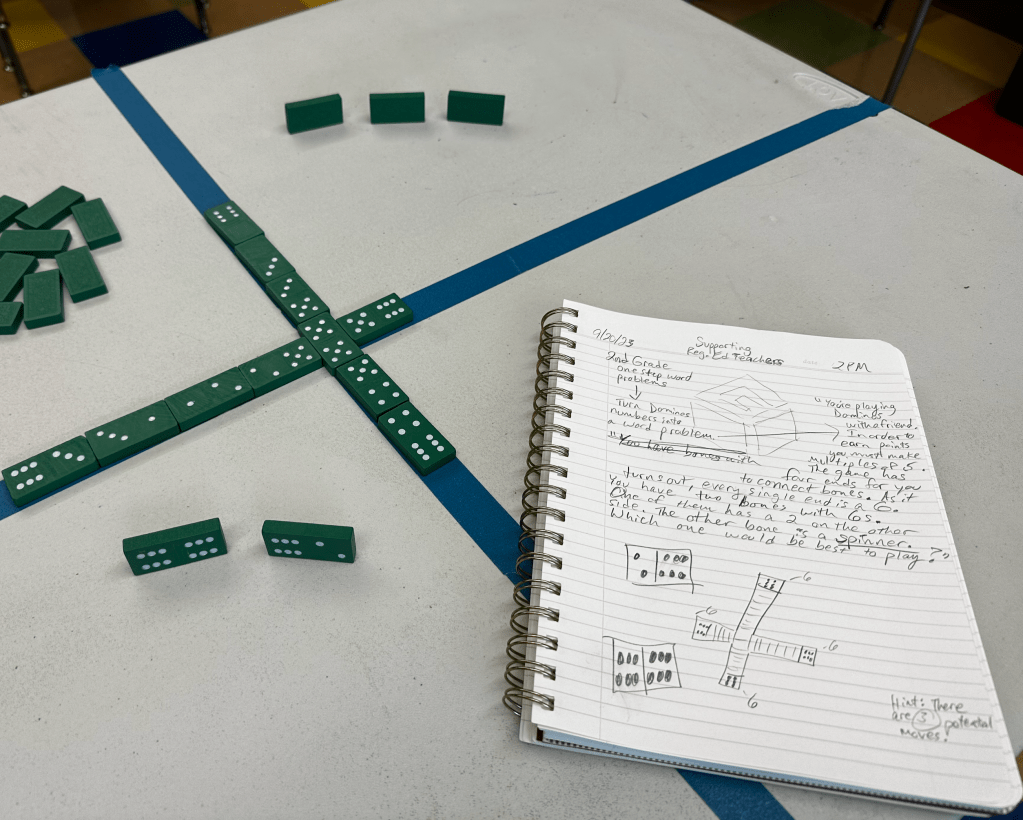

The Work: Arrange Bones as though they had been played in a game. This means matching the ends of Bones; Six is connected to six, three to three, etc. There ought to be four lines of play that a player can connect a Bone to.

Each player has Bones left to play. One set of Bones is standing up, with the number of Pips showing. These are the Bones that the puzzle-solver has to work with. (Normally, when I am teaching Dominoes to students, I have them lay all of the Bones down, so that every student can see all of the Pips. This is so that every single play is a lesson on problem-solving. When one plays a real game, you do not show your Bones to your opponent.)

The Bones that the puzzle-solver has to work with (the ones showing Pips in the image) should have numbers that can be played. They contain the number that is present at the ends of the lines of play. One of the Bones that can be played would cause the sum of all four ends of the lines of play to add up to a multiple of five, which is how one acquires points in Dominoes. This would seem like the best choice to complete the puzzle.

Because we want this to be a puzzle that causes Domino players to grow in their understanding of the game and not just an illustration modeling how to play, we aren’t going to make the correct answer to our puzzle be an obvious choice. A good head-scratcher will require a player to look beyond the obvious play.

If four Bones with the same number have already been played, and the puzzle-solver has two of the remaining Bones with that same number, how likely is it that the opponent of the puzzle-solver has any Bones with that number?

Here is your task: Make it so that playing the Bone that does NOT create a multiple of five is the better play.

How could this happen? If the opponent of the puzzle-solver is forced to draw a Bone from the Boneyard, rather than playing a Bone, not only will they not earn any points, but they will be growing the number of points that the puzzle-solver will get at the end of the round; The round that the puzzle-solver is now more likely to win because they have fewer Bones left than their opponent.

At the end of each round the player who uses up all of their Bones first gets points from the Pips that are on their opponent’s remaining Bones. In order for the play that did not make a multiple of five in the first place (at the beginning of the puzzle-solving exercise) to be the better play, the final play must provide more points than the potential multiple of five.

If the multiple of five would have been fifteen, and there is no way, given the Bones that are left, for the puzzle-solver’s opponent to have a total of Pips greater than fifteen (you always round up, so sixteen would go up to twenty), then not playing the multiple of five during play would not necessarily be a winning strategy. Typically, you would play the multiple of five, get the points, and hope for the best. This exercise is designed to show my 5th graders that if you plan ahead, the delay of point acquisition could very well bring a windfall of greater point tallies. Not only is this a good life lesson, but it can help them play the game better in the future.

Now, if you want to try to figure out how to create a puzzle that fulfills these requirements on your own, without any help, go for it. You can return to this writing when/if you get stuck and need some guidance. The next section provides some helpful hints.

If you aren’t sure where to start, or you have hit a mental block, check out these ideas.

Some Helpful Hints:

Limit the available Bones. You can do this several different ways. One is to only give the puzzle-solver two bones to choose from.

Another way to limit the potential outcomes is to make the lines of play long. Have most of the Bones from the set showing in the lines of play, so that the potential Bones of the opponent is narrowed to only a few possible numbers. The puzzle-solver can reverse-engineer the game to figure out what Bones are left to be played. It’s like “card-counting,” but legal;)

A very effective strategy for creating a doable puzzle is to limit the numbers in play. Idea: Make the ends of the line of play all the same number, and the puzzle-solver has the remaining Bones that contain that number. For example, there is a one at the end of all four lines of play. There are only seven Bones that have a one in them. If four of these are played, and the puzzle-solver has the remaining three, then the opponent cannot possibly play any of their Bones.

But, the puzzle has the puzzle-solver making the next play. How can the puzzle-solver cause their opponent to have to draw from the Boneyard? See if you can figure it out.

There are a couple of ways to solve this problem. One answer is to provide the puzzle-solver with a double. A double has the same number on both sides. When this is played at the end of a line of play, it keeps that number going!

Another solution requires more work, and could therefore be trickier for the puzzle-solver to find. Make it so that all of the Bones that the puzzle-solver possesses have numbers on them that can’t be played. You have to position every bone that has any of the other numbers on them within the lines of play. No need to worry about your puzzle-solver using up their Bones because every one of theirs contains the same number as the ends of the lines of play.

Stack the Pips. Create lines of play that have low numbers, thus ensuring that the Bones that the opponent possesses are more likely to have higher Pip counts. In this way, even if the puzzle-solver would make a fifteen or twenty with the false-solution-Bone (the one that would make a multiple of five and seems to be the better choice for the puzzle-solver to choose), the total Pips that the opponent would have must be greater than the multiple of five. This number work is truly statistical thinking. Out of all of the Bones still available, how likely is it for the opponent to have a high enough number of Pips for the counterintuitive play to benefit the puzzle-solver more?

This puzzle would allow for the opponent to make a play or two before the puzzle-solver is out of Bones. My student would have to work through all of the possible outcomes to ensure that the puzzle-solver would come out on top.

Try it out, and make the puzzle fool-proof. When making the puzzle, turn all of the Bones over so that the Pips are showing. Create a model of lines of play. Give the puzzle-solver the Bones they will work with. Now, look at the Bones that the opponent could have. Adjust the lines of play, so that there is no possible way for the opponent to have a way of winning. You also have to double-check that there are only Bones that would cause the opponent to have more Pips than the false-solution. Then turn over the Bones that form the Boneyard, and stand up a couple that represent the unknown opponent’s Bones.

Conclusion:

Normally, I will do a lesson like this, and then write a blog about it. This is different. I have used my writing to think through what I want to have my 5th graders do.

My aim is to have them build their understanding of the game of Dominoes and learn statistical analysis through the process of constructing their own puzzles, rather than just solving mine. Hopefully it will be successful, and I can write a follow up blog about how wonderful it went… or the lessons I learned through its execution, pun intended;)

If you try this idea or one like it, please share your results. I’d love to learn feedback and improve future teaching.

Sources:

Marcus, M. (2020). How to Play Dominoes . Cool Math Games. https://www.coolmathgames.com/blog/how-to-play-dominoes