In preparation for teaching a math enrichment lesson to my fifth graders, I looked at the iReady “Extension” activities in the Ready Math “Teacher Toolbox,” and I found a problem that I liked a lot. (iReady and Ready Math are products of Curriculum Associates. My district has been using it for several years, and I like it a lot.) This lesson (14) is all about using fractions to solve word problems.

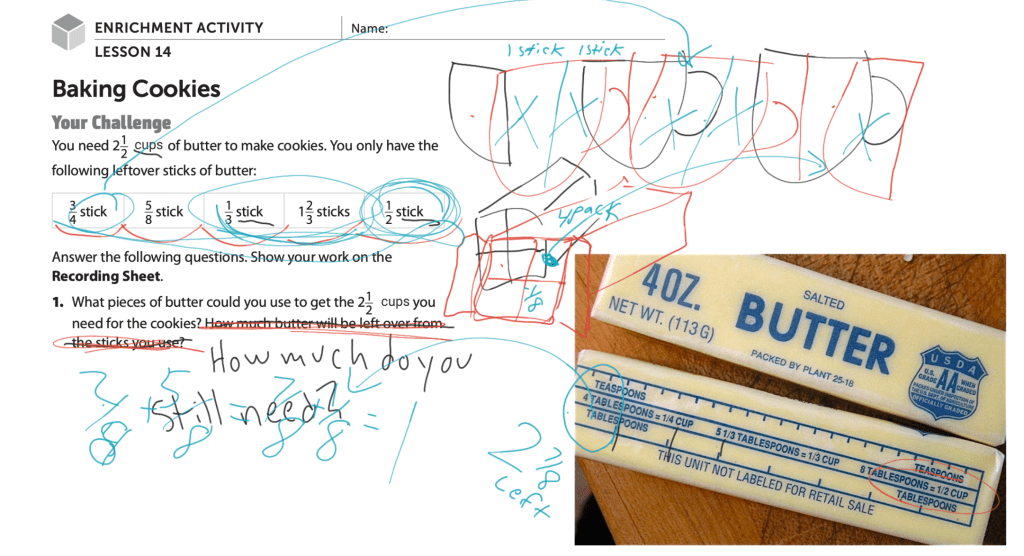

Here’s an image of the worksheet that a teacher could photocopy or share via Google classroom. Because I have the luxury of actually teaching enrichment lessons, I decided to do some explaining before handing over the problem. Also, I opted to make a few tweaks, too. In my experience recipes usually call for specific measurements of butter, not a number of “sticks.” Therefore, I covered up the word sticks in the problem and wrote in “cups.”

This changed the outcome of the answer quite a lot. Now, students would not have enough butter to complete the recipe. They could access new sticks of butter, but if they did that, then solving the problem wouldn’t require wrestling with all of the fractions presented in the partial sticks. That’s when I imagined the real-life experience of baking cookies after having worked all day at making a big meal, like Thanksgiving.

Needing soft butter for recipes is a real thing. Also, who doesn’t love consolidating? We can clean up all of those partial sticks of butter and make cookies at the same time!

I shared what a typical day of cooking in preparation for a large Thanksgiving meal looks like at my home with my fifth grade students, setting the stage for having several fractions of sticks hanging around. With the instruction to use up the warm butter first, and then dip into the cold butter from the new package, I set my students loose to calculate how much butter would be left.

Many students jumped on adding up all of the fractions. They began figuring out compatible denominators, so that they could combine every partial stick and find out what they had in all. “But, do you have to do that?” I asked them. No one wanted to venture a guess.

“What are you asked to find?” I pressed.

“Two and half cups of butter,” someone accurately answered. Without saying anything, I drew two of the worst cups ever drawn on an interactive board, followed by half of a third. I made fun of my drawings, which everyone helped with, pitching in their own digs. Once that settled down, I pointed out the lines I’d drawn through the middle of each measuring cup.

“Why’d I do that?” Earlier, we had discussed that fact that one entire stick of butter was the equivalent of half a cup. The students understood better than they could put it into words, so I articulated the concept for them, “Each half of a cup was one stick of butter.”

Then, we looked back at the fractions. It was easy to see that 1 2/3 + 1/3 would be able to fill one whole measuring cup. That leaves us with three fractions with differing denominators. “Before working out a common denominator to add up all three, think about what you are trying to do,” I instructed. “What is your aim?”

I showed the students that 1/2 a stick of butter + two of the 3/4 would equal one whole. “That would take care of half of a measuring cup,” I told them. Also, I should mention that I crossed out halves of measuring cups, as we discovered combinations of partial sticks of butter that would fill them.

“If we used up two of the quarters to combine with the 1/2 a stick and create a whole stick, how many quarters are left?” One quarter. “And then, we have 5/8 of different stick left.”

They instantly got it. We were 1/8 short of a whole stick of butter. In the end we needed one whole cold stick of butter, plus 1/8 of an additional stick to add to all of our warm butter fragmented sticks to fill our two and a half measuring cups.

The Ready Math extension lesson (14) has a second question that I left as is. The catch is that my students used our additional left over cold butter (2 7/8 sticks) from my adapted first problem to solve it. I let them struggle with this one for a few minutes before I showed them the short cut of drawing pictures.

“You might think it childish to draw pictures,” I began. Fifth grade is the oldest grade in my school, so these were the seniors of the place. “…But, I find it easier to manage some problems when I sketch what is happening.” I had been watching them crunching numbers, making common denominators again, and subtracting fractions. Now, within a handful of seconds, I showed them how many quarters could be made from two sticks of butter! I pointed out the idea of labeling the quarters in order to keep track of my thinking. I wrote a B above each “batch” of cookies. Sure, I could just count the quarters, but when it came to the last stick, it will be important to identify what portions of butter will complete a batch.

As I divided the last rectangle into eighths, I asked, “What am I doing to this last stick of butter?”

Rather than answering my question, they were chomping at the bit to be the first to spew the solution to the problem. “Eleven and 1/8!” more than one fifth grader shouted at the same time.

“No, that’s incorrect,” I casually, but cautiously counseled. Rewording what they had yelled in order to make plain the problem with their answer, I said, “You cannot make 11 AND 1/8 batches.” The emphasis on the word “and” did the trick.

“You can make eleven batches, and you’ll have 1/8 of a stick left over,” a student corrected.

“Perfect,” I affirmed. “Drawing pictures might seem silly, but look at how simple it is to see the answer. We didn’t do any denominator work past doubling up the number of sections in the last stick. I hardly did any math, beyond simply counting!

“When you are taking standardized tests, you get scrap paper. Use it. Draw pictures. Illustrate word problems. Take the time to label parts of your illustrations. Make sure that you understand what you are being asked. What is your goal? What are you supposed to find? It’s not just a number. It is the solution to a problem. In real life, it is a key that will unlock a problem. Be a problem-solver; Not a human-calculator,” I told them.

In conclusion, my aim is to turn these advanced math performers into problem-solvers. With this goal in mind, I try to make lessons that force students to use what they have learned in their regular math class in a way that is not only compatible with what they would find in the “real world,” but forces them to understand how to use the skills. I often allow my students to use calculators because the problems I prepare for them require more knowing what to do with the numbers than practicing running through algorithms. AI can learn how to crunch numbers, but will it be able to successfully manage a kitchen full of amateur chefs laughing, telling stories, and making meaningful memories, all the while measuring butter for cookies after already cooking and eating a Thanksgiving dinner?

To combat the threat of AI, don’t try to make humans better than machines. That just makes them more like machines. I say, grow the human-ness of students. This is getting pretty deep, so I’m going to go eat a buttery cookie while I chew on these ideas for a future blog;)