During an interview for a podcast with Curriculum Associates the other day I was asked how I use real world scenarios to enrich math lessons. I had explained to the interviewer that teaching is a second career for me. My experience of entrepreneurship as a residential custom painting contractor helps me introduce loads of business expertise in my math lessons.

The interviewer was looking to provide practical solutions for teachers to use. I took two seconds to imagine I was sitting in front of my computer (as I am right now;) and tried to remember the steps of making my lessons.

The first thing I do is find the lesson in the i-Ready toolbox, and look at the “Extend Learning” assignment. I don’t usually use the i-Ready assignment verbatim, just in case the regular education teacher wants to assign it. I use it as a guide for my enrichment lesson.

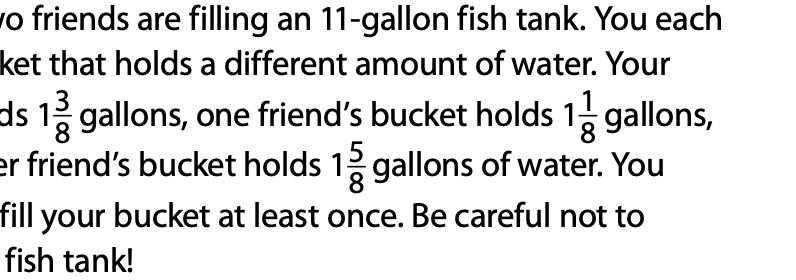

For instance, this week my fourth graders were learning about adding and subtracting mixed numbers (Lesson 21). The extended lesson shares a story about a couple of kids filling a fish tank. Some mixed numbers are used, and kids are asked to do calculations that would require them to add and subtract the mixed numbers.

I actually have a 75 gallon fish tank in my classroom, so this story could very well be perfect. However, I just wasn’t feeling the mixed number connection. There is no way that three friends would have three different buckets that all hold different mixed numbers of water with a fraction containing the same denominator. It felt too implausible.

I sat at my computer and thought, Where do I encounter mixed numbers? In addition to having run a successful business, I’m also a “Do it yourself-er.” I enjoy building things. Making things with my own hands and tools is satisfying to me. I made the stand that my fish tank sits on. I finished my own basement, complete with bathroom and laundry room. In short, I have come across plenty of mixed numbers! Developing an enrichment math lesson that uses mixed numbers will require me to make the work of adding and subtracting the mixed numbers both doable and easy enough for the fourth graders to understand. That is my challenge.

The morning that I came up with “Fix a Bench” my first thought was to have my students figure out how many boards would fit on a small deck surface. Each board could be a mixed number in width. This would be similar to the fish tank assignment from i-Ready. Kids would just add them up to fill the space.

As I began researching and looking for pictures online to jazz up my presentation, I remembered that lumber is full of mixed numbers. The most common building material, the two by four, is NOT really two inches by four inches. I learned this ages ago when I expected several adjacent two by fours to equal a nice even round number. It was some wacky measurement, and I took a closer look at the dimension of the studs (two by fours) I had purchased. I was incredulous, thinking I’d been ripped off!

Thinking this might be a fun fact to share with my students, I decided to have them explore having to use various sized pieces of lumber to make something. The fourth graders love mysteries, and I would wait until the very end to explain why two by fours are called that when they actually aren’t those dimensions.

My lesson was originally “Build a Bench.” When I began planning what my students would actually do, however, I figured out that it would be easier to teach and explain if I had them only choose lumber to place onto an already existing frame of a bench. Thus “Fix a Bench” was born.

The next part of developing a good real-world lesson is to create a “Sell.” You must come up with a pitch to draw the students in. “Today we’re going to fix a bench” isn’t good enough. Instead, I told my students that “It’s your parents’ anniversary (or birthday for single-parent families), and you want to give them something, but you have no idea what! They have a special bench that they like to sit on, but the wood is rotting. You get the idea that you will fix this bench for them as a gift. Because you don’t have enough money to buy the wood to do the work, your parents agree to get it for you. Your labor and thoughtfulness is the present. In exchange for your parents footing the bill, you have to tell them exactly how much the lumber will cost.”

This little story makes sense to the students. Even if they don’t have a bench in their backyards or don’t have a backyard at all, they can imagine doing this kind of thing. Also, it gives them some good ideas of how to come up with presents for their parents that won’t cost them anything more than creativity and thoughtfulness.

“How much does the wood cost?” the students instantly want to know.

“Before I tell you the costs, I am going to need a helper… This person has to have very good penmanship. I will know that they can write very neatly by how well they listen to the explanation of the project…” I share this with a very stern look in my eye, as I scan the room for anyone not paying close enough attention. Every student straightens their body and widens their eyes. I proceed to share the dimensions of the bench frame.

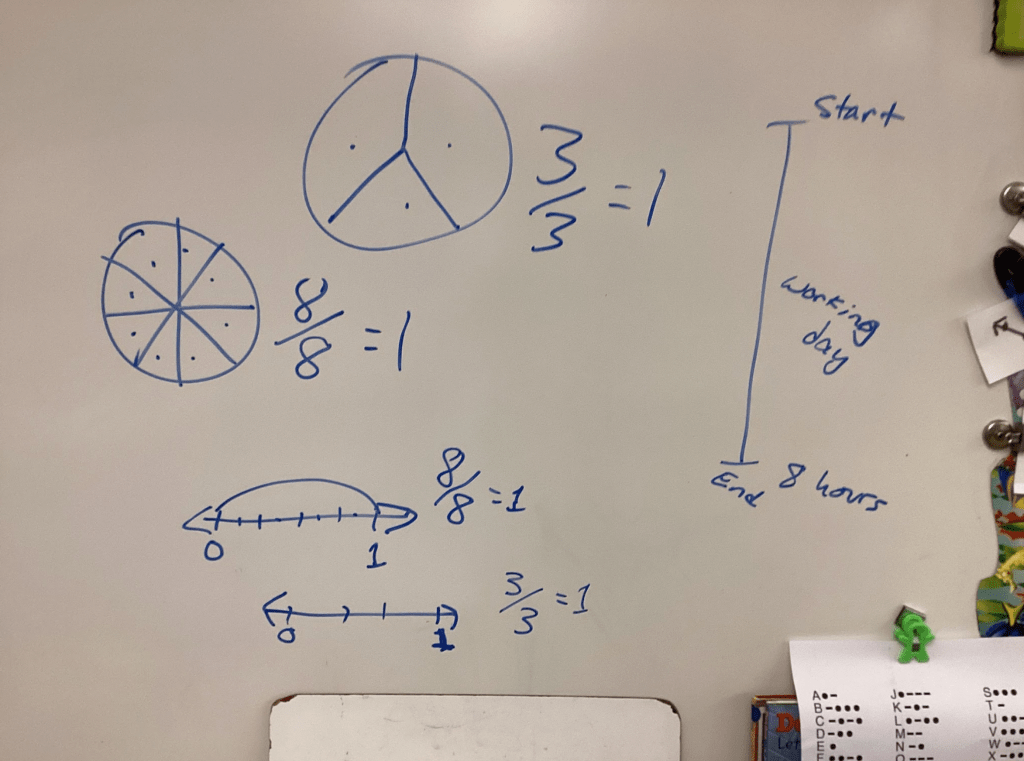

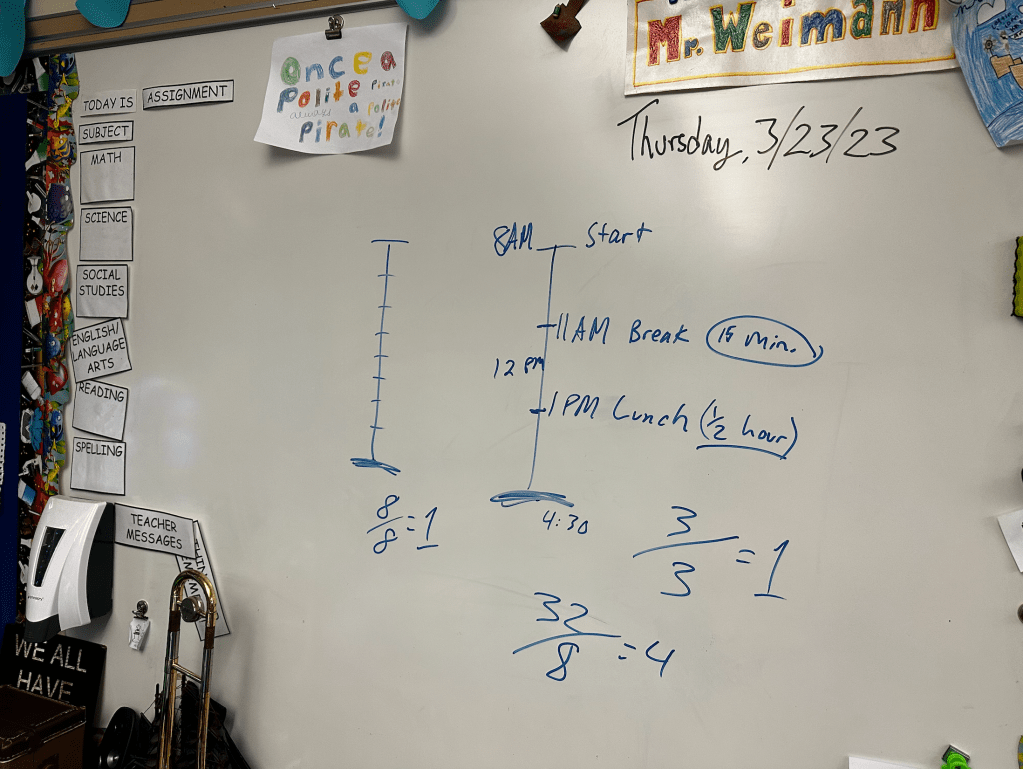

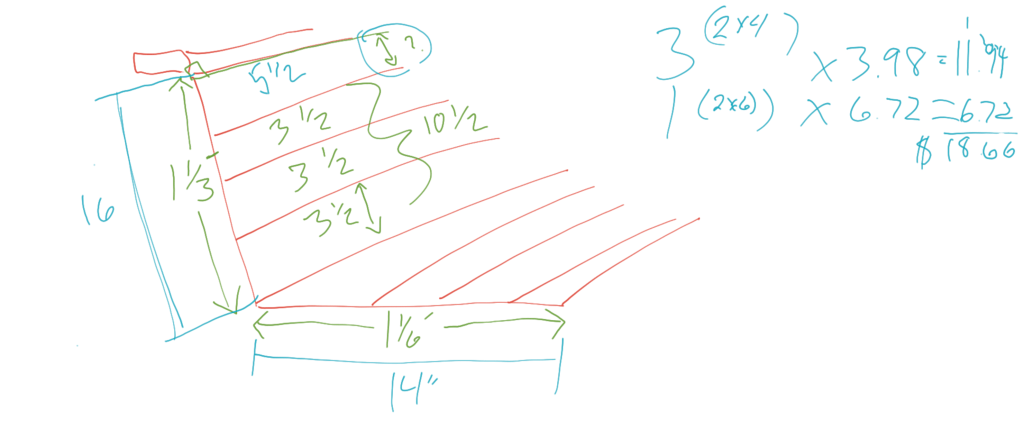

I got the size of the bench by measuring one of the chairs in my room. The back was approximately 16 inches tall, and the seat was 14 inches deep. Instead of supplying these simple numbers, I turned them into mixed numbers. Sixteen inches turned into 1 ⅓ feet, and 14 inches transformed into 1 ⅙ feet. In order to narrow the focus of calculations, I made the bench exactly eight feet wide. This way, there wouldn’t be any trimming of the ends of the boards. Just choose eight foot long pieces.

Now, it was time to show the students the materials available to them. I had found a list of lumber online that showed the names of the wood with the actual dimensions next to them. With this image on the screen in front of the class, I showed students how a two by four is actually 1 ½ inches by 3 ½ inches. A two by six, another common board measurement, is really 1 ½ inches by 5 ½ inches. And, a two by eight board is 1 ½” by 7 ¼”!

The class needed a little guidance to get started with this lesson. I guided them through drawing a diagram of the important parts of their bench. We labeled the back, the seat, “And don’t forget about the single board that goes on top!” I told them. I had them figure out how many inches the mixed numbers would translate to. “Now, we have to fill these spaces (16 and 14 inches, respectively) with lumber,” I told them. “It would be easy if two by fours were actually two inches by four inches, but they aren’t! See if you can figure out how to make sixteen inches of surface using these mixed numbers.” I circled the widths of the “two bys” from the image. I had told them that we would only use those, because they need to be thick enough to hold a human’s weight.

Using only 3 ½ (the width of a two by four) won’t work for the back of the bench. My students figured out that four of these boards will get you to exactly fourteen inches of wooden surface. That leaves you with a two inch gap, and “We don’t want any spaces. Neither can we saw any boards to resize them. There aren’t any boards that are exactly two inches wide. Can you take away one of the two by fours, and find a different size board that fits nicely?”

When my students take 3 ½ away from fourteen, they have 10 ½”. “What is the size of the space, now?” I ask this while pointing to a gap that I’ve illustrated on my drawing of the bench we are fixing. They figure out that the empty space is exactly 5 ½ inches wide. “Are there any 5 ½” wide boards that we can purchase?” Yes. The 2 by 6 is that width.

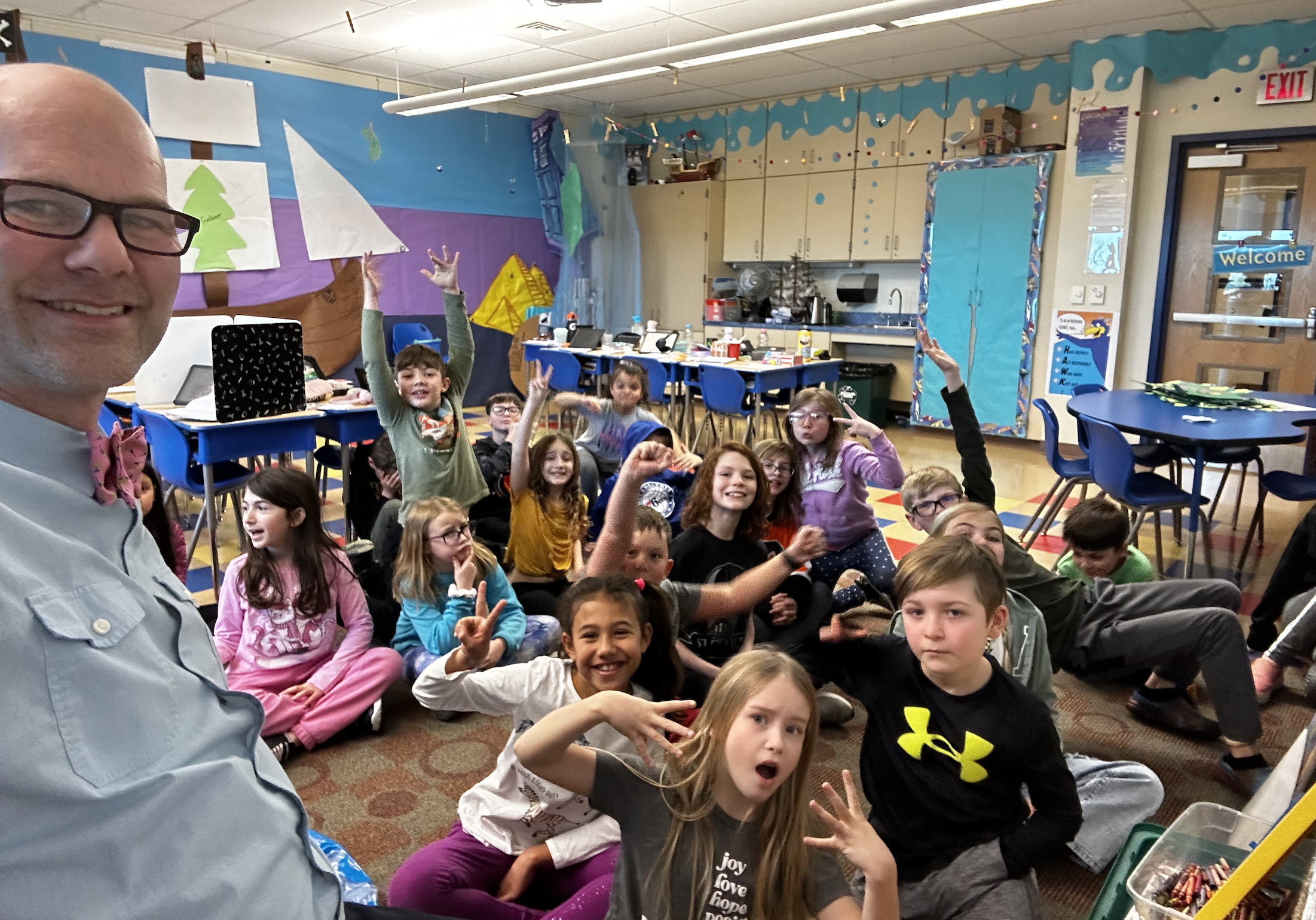

Are we done? Definitely not! “You were all such hard workers and very good listeners that it is very difficult to decide who could be my writer,” I tell my class of math enrichment fourth graders.

One of the students actually volunteered another, saying, “Nahum has really good hand-writing. You should have him write on the board.”

“Are you nominating your friend?” I inquire. He admits it, and several students second the nomination, suggesting that Nahum really does have good handwriting. “Well, okay, then. Come on up here,” I extend the invitation and commend Nahum’s friend for being classy.

As Nahum prepares to write on the board, I open my laptop. I have pricing from a lumber yard ready to go. We now write down the amount of money each board will cost us. I have Nahum give the writing tool to other kids after he writes a couple of prices, so that more students get a chance to write on the board. We only supply the prices of the two-bys, because those are the only ones we are using.

Students proceed to figure out the cost of 3 two by fours and 1 two by six. When they think that they are done with the project, I point out that we still have to figure out the seat of the bench. They happily begin problem-solving that challenge independently. It took a surprising amount of time for them to figure out that we had already answered the question of what boards could be used. The 4 two by fours that we had added up earlier had totalled exactly fourteen inches, which is the size of the seat!

When they began adding up four prices of two by fours, I pointed out that we already knew how much three of them cost. “Why not just add the cost of one more to the first number?” I suggest. Grateful for the idea, they do this.

Preempting the “I’m dones!” that were about to fill the room, I reminded them, “Don’t forget about that top board… The one that goes on the top of the back of the bench.” Happy groans and more pencil scratching ensued.

Just when my students thought that they were finally done, and Mr. Weimann couldn’t come up with any more surprises, I told them, “It would be very classy if you figured out how much your parents would have to pay in sales tax.” Epic groaning accompanied smiles and students beginning to hunch over their iPads. I told them to use calculators and that our state sales tax was six percent. This was the icing on the cake.

After a few seconds, I modeled for them, asking Siri, “What is six percent of thirty-eight dollars and fifty-six cents?” When she told me, I wrote it on the board for them.

Because I had created Google Jamboards with all of the information preloaded on them, I was able to see each individual students’ work. I had waited until Nahum and partners had neatly written the prices into the slide with lumber details before I pushed the Jamboard out in a Google classroom assignment. I had the software “Make a copy for each student.” Students knew that, although they were allowed to work with partners and I helped them solve several parts of the problem on the board, they had to add their own version of the details, showing their work

Before students left my room I explained why two by fours are actually mixed numbers. The lumber is cut at exactly two inches by four inches, but when it dries, it shrinks. Of course the students wanted to know why lumberyards don’t correct for this or call the wood by another name. The young minds cried foul and felt tricked! I told them that it has been this way for a long time, it is easier to say “two by four” than “one and a half by three and a half,” and the price of the wood that you feel like you are being cheated out of goes into having to store it while it dries, before selling it. It isn’t like the mill cuts a two inch by four inch pied of wood for you to bring home, you build with it, and it shrinks on your home. That would be worse. In the same way that creating this lesson required several steps, when one wants to make and use a two by four, you measure the wood, cut the lumber, let it dry, measure it again, and then you can work with it.