Who wants to see a picture of Mr. Weimann with hair?

EVERYONE, apparently. I used this hook to get students to pay attention to my pitch of wallpaper hanging. They hung on my every word.

This was a math enrichment lesson, in which I presented a real world problem that my fourth grade advanced math students would struggle through, using many math concepts that they already know. Knowing what to do with the numbers is sometimes more than half of the problem.

When I was in college (the first time;), I began painting to pay my way. Back then, it was just the outside of homes (exterior painting). Upon graduating, I conducted an informal internship with a wallpaper hanger. He taught me all about interior painting; which is VERY different from slapping paint on siding; and he trained me to hang wallpaper.

I was 22 years old, had long, curly, brown hair, and according to my students who did end up earning the privilege of viewing my old photos, quite tan (nearly all of them commented on this fact;). I worked with the professional wallpaper hanger for a little less than a year, hanging all kinds of paper in all kinds of homes.

About half of his work came from a restoration company that did insurance projects. These homes had suffered water, smoke, or fire damage.

Unlike a company that specializes in a niche of upper-middle class single family repaints, this work brought us into a wide range of residences. I worked in downtown Philadelphia and on the Main Line, a very wealthy area–This place has both Ferrari and Lamborghini dealerships, among others!

We rehung thick, tough paper on basement ceilings; and metallic, mirror-backed papers in tiny bathrooms. It wasn’t unheard of for me to have to remove several layers of paper in older homes, in order to get to a clean plaster surface.

It was fun to see so many different types of homes, meet a variety of peoples, and travel all over the area. I learned a lot about problem-solving because every job was completely different, and you didn’t get paid until it was done, and done well.

Eventually, I struck out on my own. I got married in 2000, and my wife Sonia and I started our own painting company called “Excellent Painting.”

We ordered lawn signs and door hangers, spread the word, and pioneered a full-service painting/wallpaper business that did it all! We even dabbled in faux finishes, popular at the time. Faux finish is when you use tricks and artistic techniques to make pillars and walls look like marble, stone, or wood.

Because we were the only company that could do all three, we got a lot of business, especially in the new developments that were popping up in suburban areas near where we lived. The market was ripe, and we were busy.

There are many components to running a successful business. You have to market the company, spreading the word, so that people know to call you. Then you need to return phone calls and perform estimates. Those estimates need to be cheap enough that people will hire you, but expensive enough to cover the costs of supplies and provide a livable income.

Eventually, you have to deliver on your promises. You have to be able to successfully perform the work that you estimated. Be prepared to follow up on complaints, questions, and problems. If you don’t, an infection of bad publicity will spread around the neighborhood, and you can write that group of homes off! Do things well, and reap the rewards of moving from house to house, cutting down on marketing costs and time.

Many of the skills and lessons that I learned through entrepreneurship are tapped in my teaching. Some days the professional world mixes with pedagogical practice more than others. My favorite place to bring my background to life is in math lessons.

The other day, I treated my fourth grade math enrichment class to a treat of problem-solving that had them working hard, thinking hard, and learning hard. The challenge was to help me come up with a price for wallpapering a couple of bathrooms.

I shared a photo of a bathroom that I papered several years ago. Many opinions about the bathroom were unsolicitedly shared by my students. In order to get them motivated, I asked, “Who wants to see a picture of Mr. Weimann (that’s me;) with hair?”

Instant quiet. Hands involuntarily went to mouths to clamp lips shut.

“Listen up.” I proceeded to explain that you don’t just glue wallpaper to walls. You have to perform all kinds of preparatory work.

There’s taking down old paper, because many times the rooms that you are going to hang wallpaper in were rooms that were already wallpapered. This is a lot of work. You may not know this, but wallpaper is two layers. There is the thin vinyl layer that sometimes peels off in large flexible sheets, but other times has to be slowly, painstakingly, curse-your-existence-ly chiseled off of the walls in tiny, bitesize pieces; As, you can probably tell, I have had too many experiences like this! Then there is the backing, which more closely resembles actual paper. This, you wet and scrape off rather nicely. There are all kinds of tricks to removing wallpaper more efficiently, but suffice to say, you better estimate plenty of time for this part of your project!

You aren’t done preparing the walls for wallpaper when all of the old paper is removed, however. Before you move on, you have to clean off all of the old glue! If you don’t, your new paper may not adhere properly. You do not want your new wallpaper to fall off the walls or bubble up. This process is not only messy. It can be deceiving. The glue is transparent, so that it does not discolor the wallpaper. Cleaning it off of the walls requires diligent and frequent assessments. Run your fingers over a cleaned wall. If you feel anything slippery or slimy, it is probably glue that still needs to be scrubbed off.

Once my students had been prepped with the horrors of wallpaper work, I brought out some numbers. I kept it simple with easy fractions to work with.

We would charge one whole dollar per square foot for actually hanging up the wallpaper, ½ a dollar for taking down the old wallpaper (Once in a while rooms don’t have wallpaper to remove. Plus, you want to make this a separate price so that customers appreciate all of your hard work, and it doesn’t seem overpriced.), and ¼ of a dollar per square foot for prep work. (This would include cleaning the walls, caulking cracks, and spackling holes and other imperfections that the paper won’t hide.) These prices are from when I was first starting out. I actually did this kind of thing, regularly.

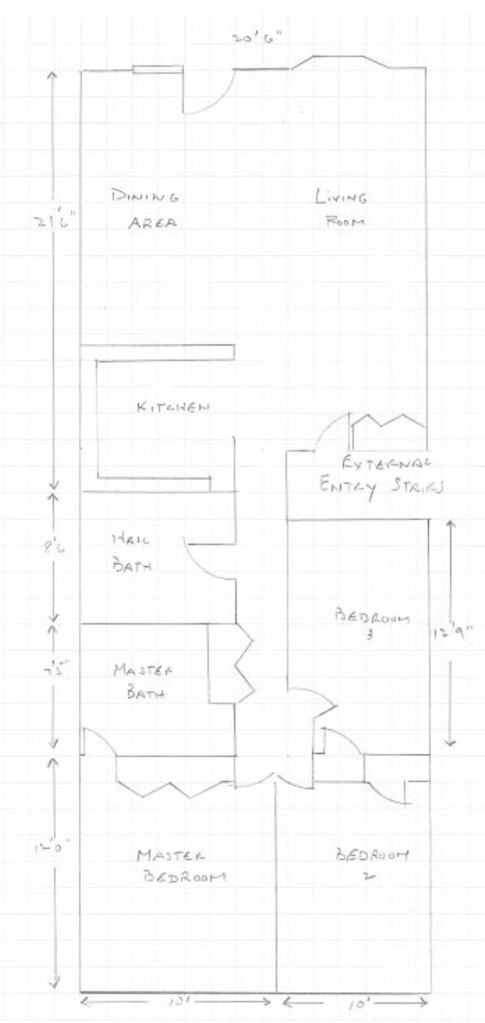

Next, I shared a simple floor plan with my students. Some of them recognized the blueprint for what it was. I showed them the illustration of doors and asked them what the rectangle representing a closet was. We discussed what was happening in the picture for a minute. And then, I told them that our customer wants to wallpaper the two bathrooms.

The image was presented on an interactive Google Jamboard, so I could write on the board. I used a bright blue to rewrite the dimensions of the bathrooms in question. I told them that the ceilings were 8 feet high. When I turned around, I was met with incredulous faces. They had no idea what to do!

This was perfect, because it provided me an opportunity to teach. I told them that a good strategy when dealing with a difficult problem is to draw pictures. I drew four rectangles beside the image of the floor plan on the Jamboard. With a little prompting I got my fourth graders to figure out that we would need to find the square footage of the wall space that would be covered with wallpaper in order to create prices. “What are these four rectangles?” I asked.

I’ll confess that the first time I did this lesson (I have an AM and a PM 4th grade math enrichment class) I tried drawing a three-dimensional image of the bathroom on the side of the floor plan, and this ended up being too difficult to understand. I ended up pulling each wall from my drawing out and making individual rectangle representations.

In my second attempt, I cut straight to the 4 walls. This was less confusing.

Either way, it required some spacial thinking to understand what to do with the numbers.

Once it was established that my picture of 4 rectangles were in fact the walls, we labeled the dimensions: Each one was eight feet high, and two were one length, while the other two were a different length.

In order to figure out the square footage of all of the walls, you solve the area of each, and add them together. This reads simple enough, but my students had never had to do anything like this before!

It took a little convincing to show them why we needed the square footage at all. I used the dimensions of our classroom and kept it to only one surface; the floor.

“How big do you think our room is?” I prompted. After a couple of guesses, I told them that I thought it was about 30 by 15. I then paced out the floor and found it to be 11 paces by 6 paces. “If we calculate each pace to be worth 3 linear feet, what are the actual dimensions of the room?” Wait for it. My students knew to multiply 3 times 11 and 6, respectively.

“Are 30 and 15 easier to work with?”

“They are compatible numbers,” Evie answered. I beamed with pride. We’ve been talking about using helpful numbers to do mental math a lot.

“That’s right; Much easier to work with. And, what is 30 times 15?” Blank stares. “What is three times 15?” Now we were thinking! When we figured out the answer to that, I wrote “15 X 3 X 10” on the Jamboard. “Thirty feels big, but pull it apart. It’s just 3 tens.”

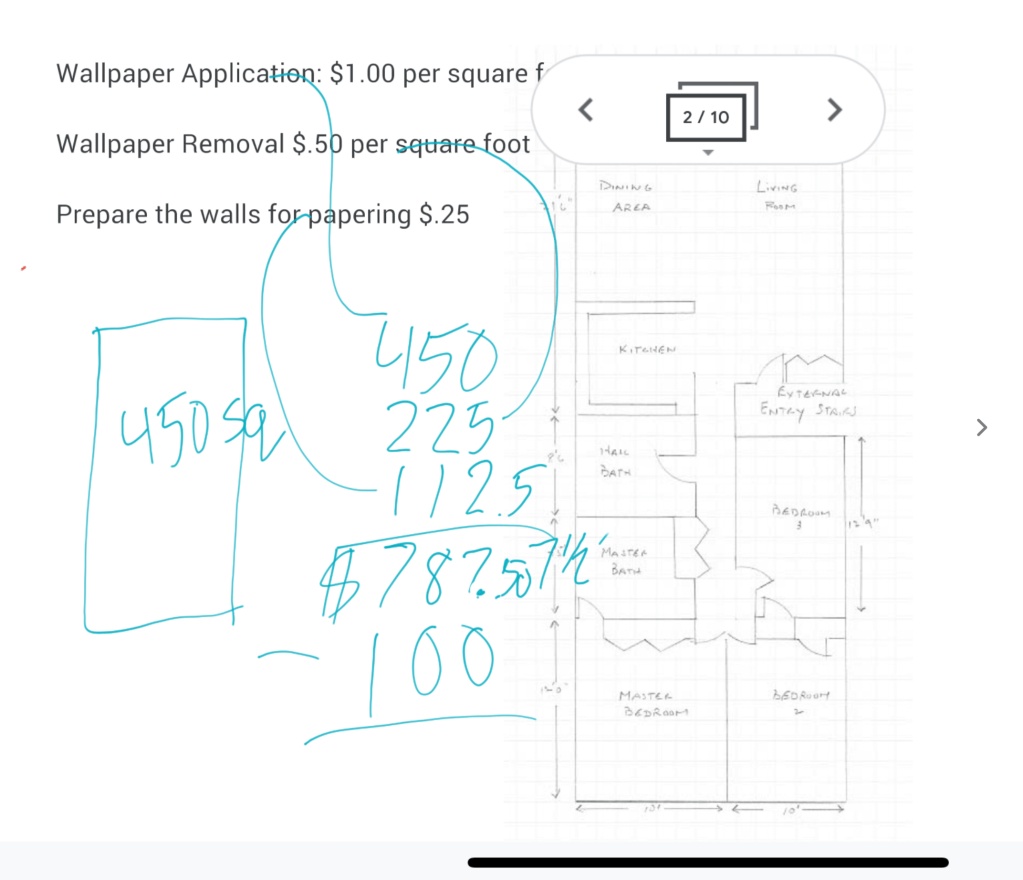

“So we know that the floor of the classroom is about 450 square feet. How much would it cost to wallpaper the floor… Of course no one would do this, but what would it cost?” Everyone quickly understood that it would cost $450, since each square foot would cost one dollar.

“Now, let’s say that some maniac had already wallpapered the floor before we were asked to. What?! Crazy, I know, but what if… We would have to remove that old paper before we can apply any new paper. How much will that cost? It’s fifty cents per square foot,” I remind them. It doesn’t take long to figure out half of 450.

“And, finally, there will be some prep work before actually wallpapering. That costs twenty-five cents per square foot.”

In order to illustrate this concept, I drew a square on a new, fresh Jamboard slide. I labeled it $1. Then I drew another square, the same size as the first, and drew a line down the middle. I labeled each half $.50. Before going any farther, my math enrichment students knew to halve the half.

While a couple of kids knew what to do with the twenty five from $225, some didn’t. I told them to break apart the number. “Don’t think of it as 225. What is half of two hundred?” I wrote 100 on the board when they said it aloud. “What’s half of 25? How do you know that it’s 12 and a ½?”

Evie-to-the-rescue-again explained that 24 divided by 2 is 12. The one extra that it takes to make it 25 can be split in half. “Nice,” I encouraged.

“So, how much would it cost to do the whole project on the floor of the classroom, provided some nut wanted to wallpaper a floor?” Staring students looked stunned. “You have the price for applying the wallpaper,” I said, circling the $450. “You have the price for removing the old wallpaper.” At that point, I circled the $225. “And, we just figured out that it would cost 112 and ½ of a dollar to prep the surface.”

“That’s right,” I said, trying to sound proud and hoping to steer my students toward feeling like they can do this. “Now, time to figure out what this bathroom would cost!”

I let them struggle a little before helping. They needed a bit of guidance. But, we figured out the square footage of all four walls. They did pretty good finding out what it would cost. And, the second bathroom was a little easier.

A funny experience happened at the very end of the afternoon lesson. This PM group of fourth graders originally entered the room with the announcement that they already knew the answer to the problem.

A couple of them had walked in on me finishing up my morning math enrichment lesson. They confessed that they already knew the final answer to be $952, “or something.”

I told them that I was going to change all of the numbers, so it will be different. They thought that sounded reasonable;)

I had intended to make the ceilings 9 feet tall for the PM class, but the concepts were difficult enough to understand that I didn’t feel like it was all that necessary. But, by the very end of the afternoon lesson, after I told the students to take the prices of the two bathrooms and add them together so that we can tell the customer how much it will cost…

“Wait,” they exclaimed. “You didn’t change the numbers!” Huge smiles stretched across their faces. They loved being tricked.

“Look at that. You ended up needing to do all of the work, anyway.” We all laughed as they exited the room.