“All of that, just to teach this little lesson?”

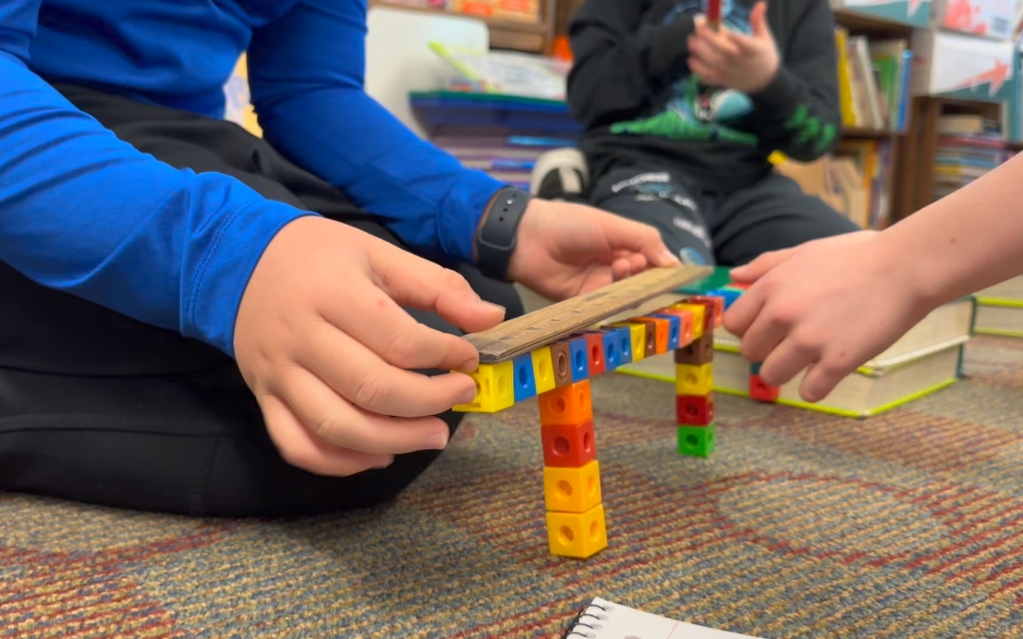

How deep does your teaching go? One way to help students understand a concept and remember the lesson is to share a story. On Thursday I was teaching an idea about fractions that was difficult to grasp. We had been working on understanding this concept all week. I had drawn models on the board and number lines on students’ papers. A few simply were not getting it. I was at a loss.

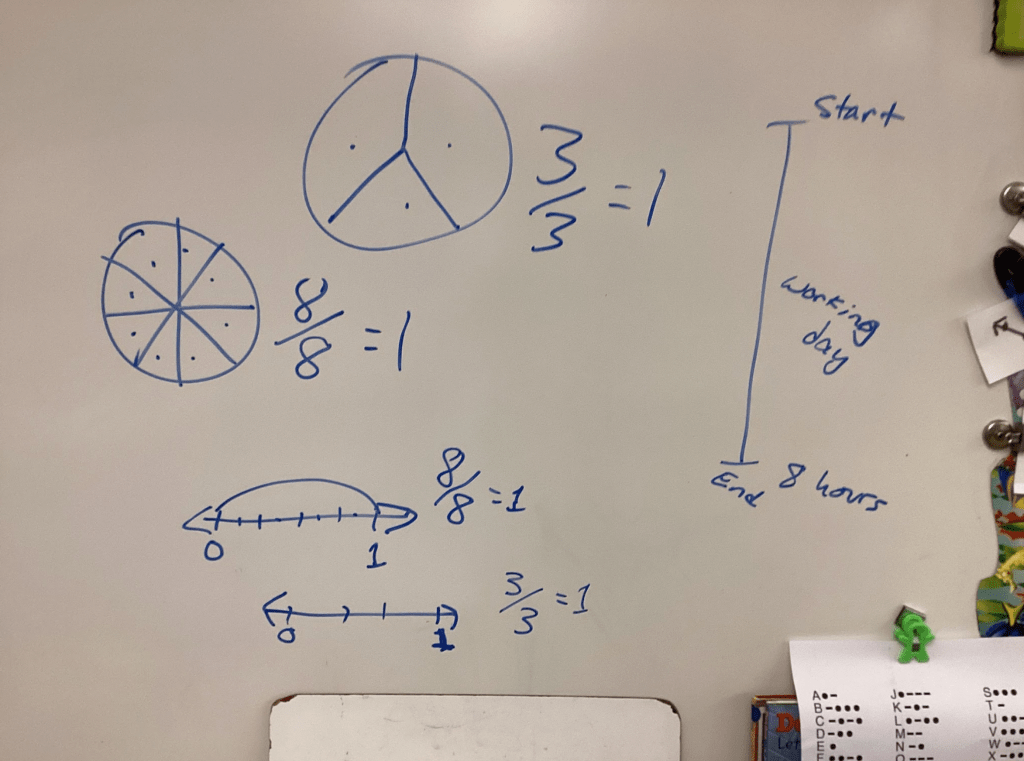

The lesson had to do with the fact that whenever the numerator is the same as the denominator, a fraction is equal to one whole. It doesn’t matter if it is 365 over 365 or 5/5, they both equal one whole. How? While I could stop at providing the rule, I like to explain the “why” of math. The following story ensued.

When I was in high school, I had the worst job! (This got everyone’s attention.) At least it was my least favorite job. I worked in a factory. What we did was kind of cool. This factory bound books. It was a book bindery. My dad worked there. He was a manager, so he was in charge of a team of people who operated different machines. He got the jobs, planned out how to complete them, gave people orders, made sure things ran smoothly, fixed machines, and was responsible for shipping out completed jobs to happy customers.

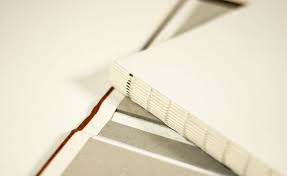

The book bindery had two parts. My dad’s part worked on orders of new books. The other part of the business would repair or re-bind old books. This part would get a shipment of books from university and school libraries in the summer. Workers would use a huge cutting machine to slice the spine of a book away. Then the front and back cover would be removed. A new cover would be made and glued onto the old pages that had been either glued or sometimes sewn together. The new cover would get stamped with the name of the book, author, and publisher. There was a different gigantic machine for each part of this process. This is where I worked for a summer right after graduating from high school.

What was so bad about it? Sounds kind of neat, right? There was NO freedom. You had to “clock in” at 8 AM, sharp. It was best to do it a couple of minutes before eight. If you were late, you’d get a “talking to.” A manager would come by and tell you that you had clocked in late too many times. One more and you were gone; You’d be fired. The manager might allow you to explain yourself, but there was no empathy. The clock was unforgiving, and you need to be on time. “Clocking in” meant getting your stiff paper card from a metal sleeve holding many cards, pushing it through a slot on the top of a metal machine displaying the time on the front. You’d push your card down until a cha-gump was heard. At the same time the sound happened, you would feel something grab your card. When you pulled it out, a time would be stamped on it.

One more thing. It wasn’t a good idea to stamp your card more than a couple of minutes early, unless you had permission. The owners of the bindery did not want to pay anyone more than they had to, and if your card had any extra time on it, they would be responsible to give you money for that time.

After clocking in, I would get to my workstation to pick up where I left off the day before. I was lucky. Whether it was because my dad worked in the other part of the bindery or I was good at it, I don’t know, but I got to operate “The Blade.” This was the gigantic cutting machine that sliced the spines off of old books. I also used it to trim the edges of pages, so that they were clean and straight for rebinding.

In order to work the machine, you would place the book onto a metal surface and push it against the back wall with the spine facing you. I would adjust the depth of the cut by turning a knob to move the book closer or farther away. When I had it just right, I would press a petal down with my foot. This lowered a metal wall that clamped the book down and held it in place. At this point I could see whether I had lined up the book just right or not. I might need to fine-tune the settings before making my cut. [I had to be careful, because if I cut off too much, the book will not have enough space on the inside of the pages for anyone to read it. If that happened, I’d just wasted an old book. You would get into big trouble if that were to happen. There are no do overs! If you didn’t cut enough off, then you could do it again, but you are wasting valuable time.] With the book held tight by the big clamp, I would push two buttons on either side of the front of the machine with the thumb of each hand, and a giant guillotine of a blade would swoosh down right in front of the clamp, slicing the spine away from the book.

Why the TWO thumb buttons? Let’s say you wanted to push a book against the back with one hand while slicing the binding away. You could accidentally cut every finger off of your hand with one fatal swish of that blade! Forcing you to use both hands at the same time ensures zero accidents.

Unfortunately, other machines had work-arounds; ways to bypass the safety procedures; and even the cutting machine could be fooled. You could tape a piece of cardboard over one button, tricking the machine into thinking that one of your thumbs was pushing it in. Basically, there were opportunities to become seriously injured on the job. While management might give someone a hard time for doing something dangerous, they would also heap tons of pressure on everyone to achieve inhuman amounts of productivity. You constantly felt like you weren’t getting enough done fast enough. If only there was a way to quicken what you were doing. What if you eliminated one of the timely safety precautions…?

At 10AM a bell would ring, and we could take a fifteen-minute break. The workers would pile into a break room in the middle of the factory where picnic (ironic name) tables were set up. We did this even if it was a gorgeous summer day. It was probably better to NOT know how beautiful it was outside! At the tables we ate snacks, drank coffee, and chatted. There wasn’t any talking on the factory floor; chatting would slow down production, so this was a time for finding out what coworkers had done the night before. We read newspapers to find out what was happening in the world outside of the book bindery.

10:15AM did not find us exiting the break room. We had better already be out of there and at our stations when the next bell rang. Anyone found lingering would get a talking to.

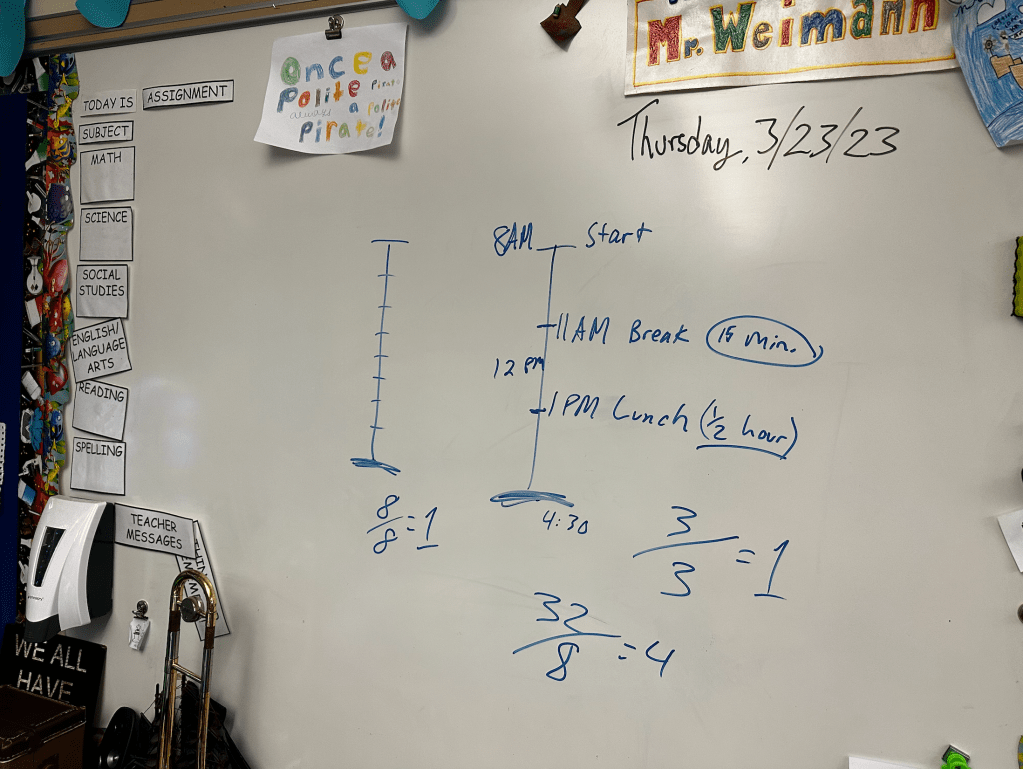

Another bell would ring at noon. [While I was sharing all of this information with my students, I was drawing a timeline of my prison-like day on the dry-erase board.] You would go back to the break room. You better have a packed lunch, because there’s no running to McD’s, even though it was only 2 miles away. I tried it once and the stress of making it back to work on time equaled more indigestion than it was worth!

The factory floor was cement, which caused your feet to hurt. I piled up cardboard boxes to stand on, and I wore sneakers with thick soles, but once your feet hurt, there was no fixing them. Additionally, even though there wasn’t much of a dress code, we did have to wear pants. It was summer time when I worked at the book bindery. Even though the place had air conditioning, the owners were constantly adjusting the temperature to use as little power as possible. It always seemed a little too hot.

It was difficult to avoid counting the hours between breaks and leading up to quitting time. When would the final bell ring?

Now, we get to the math of the story. I look to my students for an answer. Who can help me get out of here? What time did the final bell ring? I began my eight-hour day at 8AM. One student guessed, “6PM.”

“Was that a guess, or did you work that out?” I query. “Come on. Think. Eight to Noon would be how many hours?”

Another student half-guessed, “5PM.”

“You’re getting closer,” I hint.

You can probably imagine that someone figured out that eight hours would take me from 8AM to 4PM, but we have to account for the half hour of lunch. The owners aren’t going to pay me to eat. That was my time. The 15 minute coffee break in the morning was included in my work day. (Probably, this was meant to fuel productivity with a caffeine jolt, not to mention relieve the tension of not being able to talk all morning.)

Let’s say a guy has a medical condition that requires him to drink some medicine on the hour, every hour. If he takes a drink each hour of an eight-hour work day, his day is split into 8 parts; 8 hours = 8 parts. He doesn’t miss a dose, so he has had 8/8 drinks per day. The 8/8 is one day.

I didn’t need to stop and take a drink. I only stopped during the allocated break times. With only two breaks, my day was split up into three parts. I work all three parts, so I work three out of my three parts. My 3/3 day is only one day, also. My friend and I both work a full eight-hour day, but mine is simply divided up differently.

8/8 = 1

3/3 = 1

8/8 = 3/3

I’ve drawn timelines (number lines) on the board. It is easy to see that the same amount of time is broken up differently.

If my friend keeps his medicinal drink in a 32 ounce water bottle, and his dosage is one ounce per hour, how many days will he be able to use the bottle before he has to refill it?

How many doses will one day be? With each day broken up into eight equal parts (hours), the denominator will be 8. The total number of ounces (32) will be the numerator. The improper fraction will look like this: 32/8. Is there enough medicine for more than one day? A lot more. How much more?

How many eights go into 32? Or, how many eight-hour days can the 32 ounces be stretched over? You could do repeated subtraction. The water bottle will last four days.

Before leaving this story and transitioning to a different lesson, my students had to know why on earth ANYONE would work at such a horrible place. I told them that there are pros and cons to nearly everything. First of all, this could very well be the only job that some of the workers could get. The book bindery employed many people who did not speak English. Once they were trained on how to operate a machine, they could do their job efficiently, and it didn’t matter that they could not communicate via the same language as the owners. Occupations that require more communicating might require people to know English.

But, I knew English, so why did I work there? It was a summer job, and although the hourly wage was not very high, it was the only place that offered a full 40-hour work week to a temporary employee. Other businesses weren’t interested in investing training in a worker who would only be there for a few weeks. Also, if I worked over 40 hours, which the boss wasn’t too keen about, I’d get “time and a half.” Ooooh, I feel more math coming on… Groans.

Many businesses only offer benefits, which include health insurance, to “full-time” employees. This title belongs to people who contract or agree to work a 40-hour week. Sometimes it is worth working a less attractive job, so that you can keep your family safe by having health insurance. This is the American way.

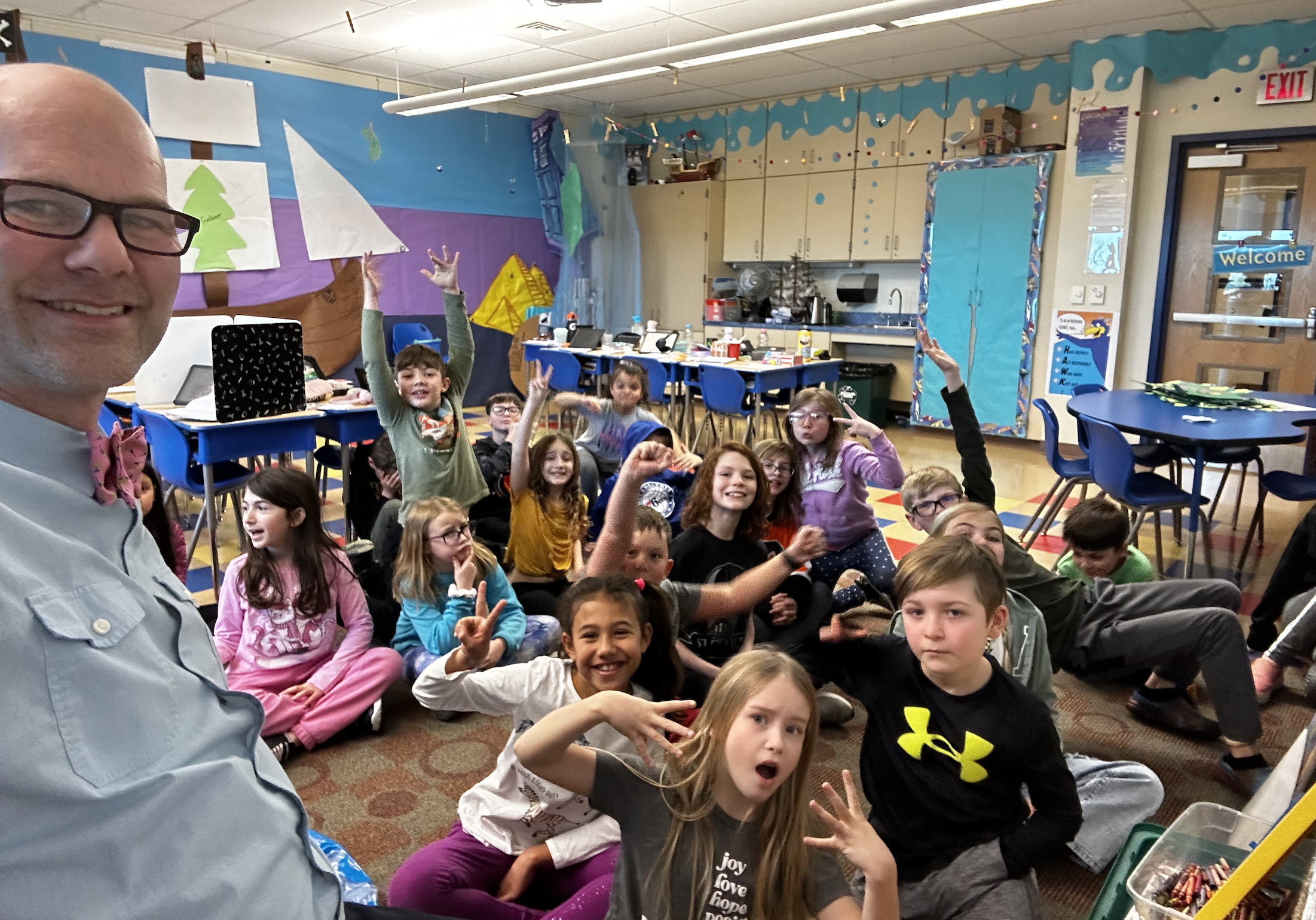

I’ve told the Polite Pirates (my students) all about running my own painting business before becoming a teacher; There’s lots of math in those conversations! At this point in my explanation I point out that while running your own business means you are the boss, and you have freedom, it is a lot of work! Had the stress of making sure that I had future painting projects to do, because if my work dried up… Then what? There’s no money coming in! So, I had to do a lot of marketing, and that costs money. Then I had the pressure of finishing projects on time. Sometimes I had to work more than 40 hours in a week. Because I set prices with customers before beginning the projects, I didn’t make any extra money if I worked longer hours! And, what if I priced it badly? What if I thought that a job would be lucrative if I charged 300 dollars, only to find out that the product needed to complete the job would cost me $250? Don’t even get me started on spilled paint…! How much of that profit would be left if I had to buy a customer a new carpet?

Working at a factory is, believe it or not, liberating from the stress of all of that responsibility. You punch in your time clock, put in your hours, punch out, and leave all of the thoughts of work at work. What you didn’t complete will be waiting for you to finish tomorrow. Let the manager stress out about how a job is going to get done.

Finally, although this all sounds kind of awful, I am glad that I had the experience of working in the book bindery. I learned all about how books are put together, which was interesting. But, more importantly, I got to see first-hand a type of life that I may not have known had I not worked there.

As I rose from my chair to erase my notes from the board, my students understood that all of that was to teach a simple lesson on fractions. “All of that, just to teach us about whole numbers…?” a few students said in surprise. Yup.