I’m back with some more Dominoes word problem work. At the end of my last blog about Dominoes I dreamed up what I thought would be a good problem to get students thinking. It seemed not only doable to me, but I worried that it might be too easy. Not so.

I asked my students, “What is the highest score possible in one play of Dominoes?” I put 28 bones (one whole set) on each table, and encouraged students to move them around looking for the best combination.

A game of Dominoes proceeds until one player or team acquires 150 points. It takes several rounds to accumulate that many points. During each round the players add Bones (Domino pieces or tiles) to an existing cross of Bones. You have to connect the same numbers, so a 6-4 Bone could not be added to a 5-1 Bone. It could be added to a 4-4 or a 6-6 Bone. When you connect a new Bone to the Line of Play, you add the last number from each end. Your goal is to have a sum that is a multiple of five. Only multiples of five get recorded as points, pushing you closer to the goal of 150; victory.

The first group that I met with are 5th graders. They are still learning the game. I thought that providing the question of figuring out the very best play would create a goal; “This is what I can aim for.” Instead, my students began building towers with the bones and grumbled, “Why don’t we just play Math 24?” Upon self-reflection, I now realize that my word problem was like asking someone who is just beginning to learn how to construct an airplane to calculate how fast it will go. “Dude, let me get the wings on this thing, already!” Ha, ha. Sorry, students.

Before wasting too much time, fostering further frustration, I decided to scrap the 5th graders’ warm up and move on. I made a mental note on the idea of a Math 24 preference, though. This gave me much to think about; More to come on that, soon.

I didn’t even try the problem with my 2nd graders, who are also novice Domino players. I thought I’d wait and see how my experienced 4th graders, the students whom I taught to play the game last year, would do. These guys would love the challenge, and should have all of the conceptual tools necessary to tackle this problem. They’re the ones in the picture on the Google Jamboard, for crying out loud!

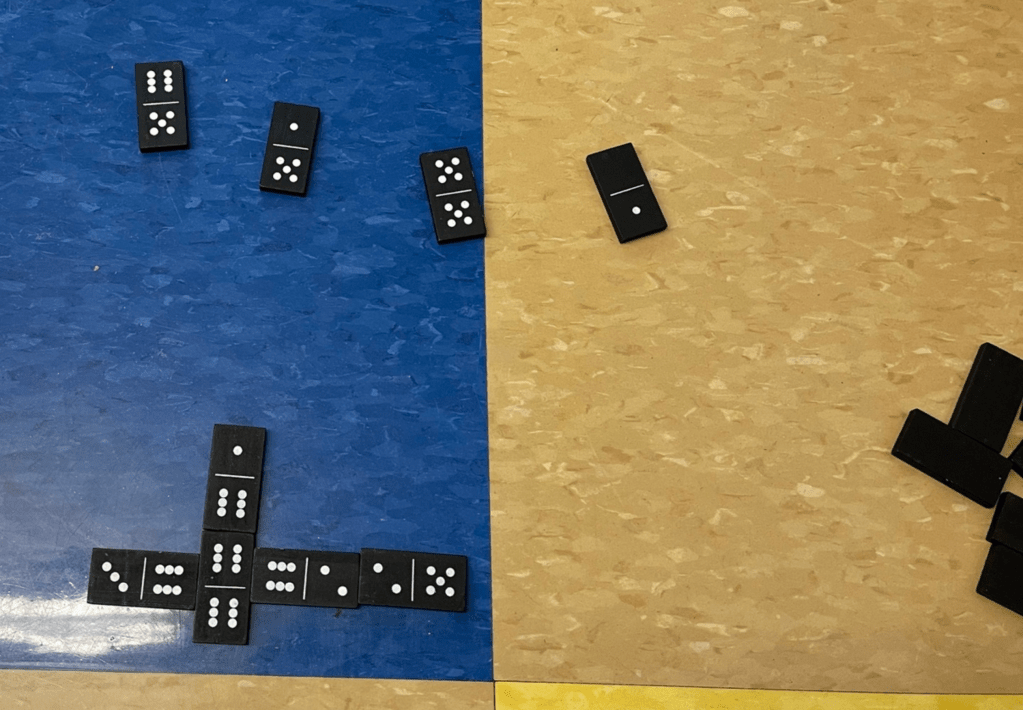

My 4th graders jumped into “Problem-Solving” mode right away. Their biggest hangup was trying to play the game from the beginning. They kept trying to build the arms from the center of the game, forming a cross they way they always do. That won’t work when attempting to find the highest possible score, though. They would have already used the Bones with the greatest number of Pips (that is the technical term for the dots on the Dominoes) on them. Those need to be saved for the ends.

I must have told them to, “Focus on the ends of all four arms. Don’t play a whole game. You don’t need the center of the cross in order to calculate the largest point accumulation possible,” a dozen times. I began to feel like a broken record.

Finally, I stopped them and taught them a new vocabulary word: Hypothetical. “This is a hypothetical situation. If you could have the ideal play; The absolute best play ever, what would it be? Don’t worry about what was already played. What Bones would give you the very highest points?”

This is truly Out-of-the-Box Thinking. I wanted my gifted students to leave the box of the game and imagine only the very last play. All previous plays are fog. They don’t matter. You can only see the tips of the Lines of Play, and they have huge Bones… Doubles, every one of them; The highest Doubles, even! Eventually, I had to just tell them the answer.

I had one last group to try out my wonderful word problem. I started the Domino difficulty by sharing with my 3rd graders that the 4th graders could not do this. That got their competitive juices flowing! Next, I did not allow them to put any Bones in the center of the cross. “We are NOT playing Dominoes,” I explained. We are figuring out a hypothetical question: “What if you had an opportunity to make a play that gave you an enormous amount of points? How many points would be the greatest possible in one play of Dominoes?”

I guided their thinking toward the Bones that represent the greatest numbers. Even though a 6-5 Bone has more Pips than a 5-5 Bone, it does not present the greatest value when played at the end of a line. Why? Because, you don’t add the 5 and the 6 from the 5-6 Bone. Only one of the numbers would be available for adding. However, if you played the 5-5 Bone sideways, you’d have ten. Gasps, sighs, intake of breaths… Doubles were explored. I forced them to put the Doubles at the ends of the lines of tape I’d stuck on the tables to guide Lines of Play.

Letting the 3rd graders figure out answers to my guiding questions, I led them through Out-of-the-Box Thinking. In the end, they felt like they had solved the problem, and they had (with a little guidance from their teacher). Lesson: People can be taught to Think Outside of the Box. It is not necessarily natural.