In order to help students understand a concept teachers often have to present it multiple ways. The more challenging the topic is to understand, the more methods might have to be used. I found this to be the case the other day when sharing the idea of ratio with my third graders.

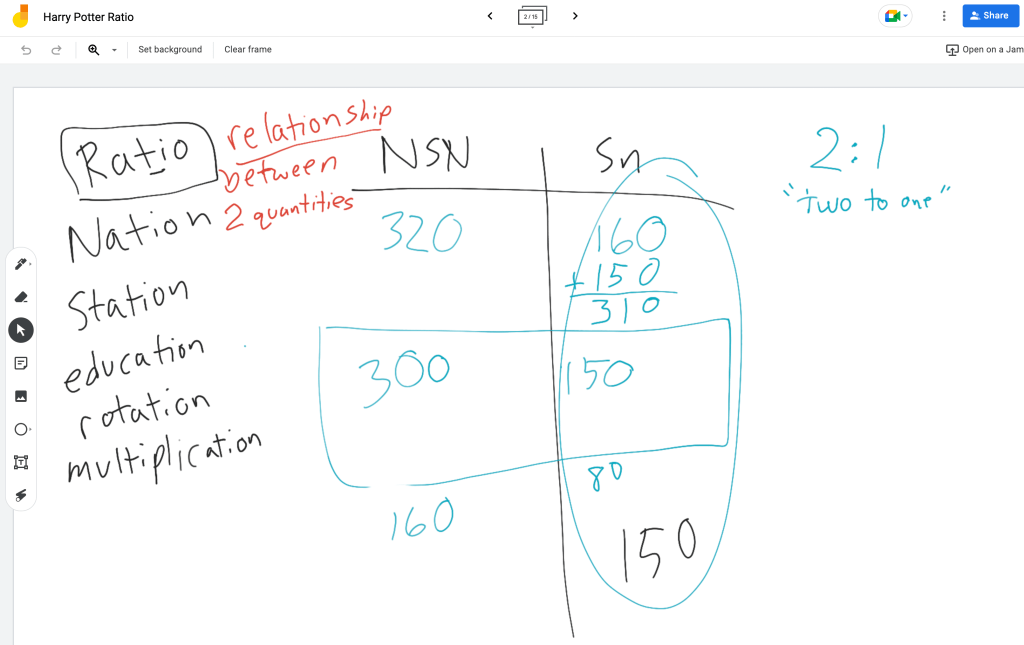

I had presented my Quidditch quandary to the class; “Can a team win a game of quidditch without catching the snitch?” We had explored the ratio of two to one. This had gone fine. My third graders could easily understand the idea of a team being twice as good as another.

I paused at this point and introduced the term ratio. I explained that a ratio described the relationship between two quantities. I made sure that they understood quantity to mean the amount of something; In this case the number of goals a team has in relation to the number of goals another team has. So far, so good.

They did okay when we changed the ratio from 2:1 to 3:1. Now, one team was three times as good as the other. Things got hairy, though, when we changed the ratio to 3:2.

At first, I tried to just use numbers to show what was happening. “If you used a number that was divisible by three, it’s easier,” I began. “You could put that number on the left side of the colon.” I wrote a twelve on the board. “Then, break it up into thirds. Put two of the thirds on the right,” I told them. “What number goes into twelve three times?”

“Four.”

“Right.” I wrote eight on the right side of the colon… “12:8.” This may as well have been Portuguese to my third graders!

As it turned out, a couple of my students spoke Portuguese fluently! Not literally.

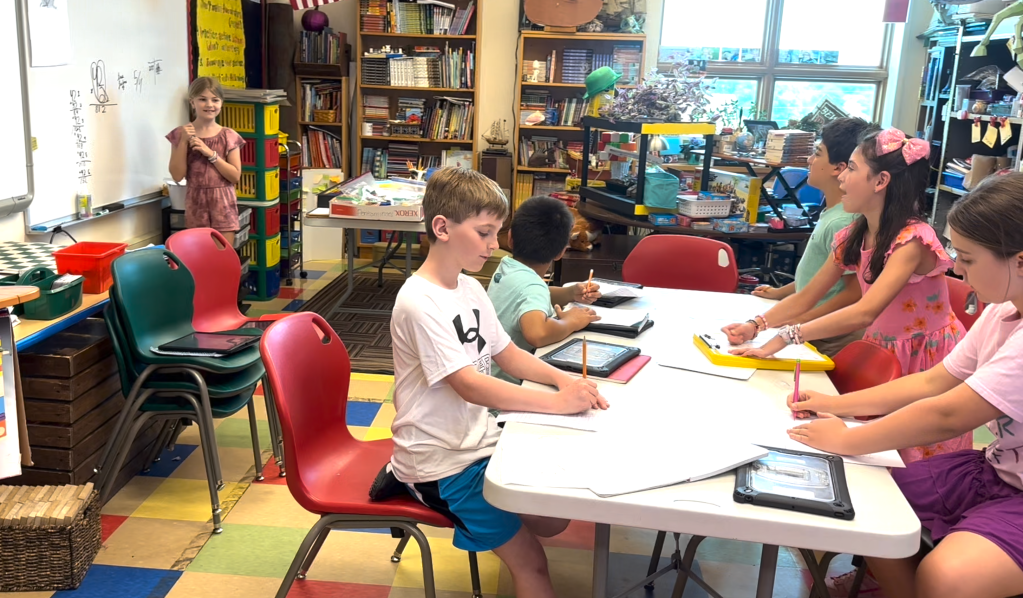

I teach gifted students. That is how I can present problems like these to 8 year olds and expect them to get them. Sometimes, like the present lesson, I have to do some extra teaching. But, for some gifted students, the math comes naturally. It is like a language to them. This is truly remarkable to witness. I captured one of my third grade student’s ratio-realizing moment on video. He used the numbers like a master painter might transition from one color to another. I was so impressed!

He had come up with 48:32 completely on his own. I wanted him to explain where these numbers came from. With a little prompting and help filling in the gaps, he and I recorded his thought process in the video I posted to X.

“I tried 45. Then I got into fifteen because three times fifteen equals 45. Then, I found out that was a tie,” the student breathlessly begins. He started to explain adding three to 45, but I interrupted him.

“How was that a tie?” I prompted.

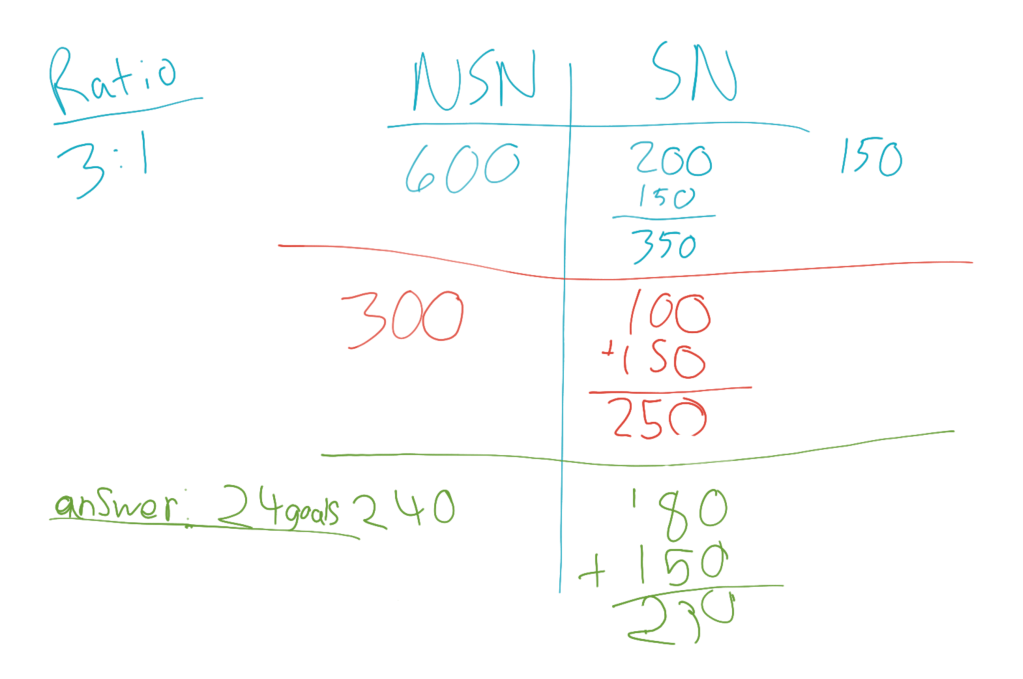

“To do that,” the student recalled, “You get thirty, which is three hundred,” writing the numbers on the dry erase board as he spoke. “Then you add the snitch, which is 150.”

At this point in the video, I (unfortunately) talk over the student’s explanation. Before I began rolling the video recording, the student had raced through his explanation in his excitement to share his finding the correct answer. I wanted to help him clarify how he new 45 was not the correct answer, before moving on to the right number. With us talking at the same time, the audio is a little cumbersome, but I just kept the feed rolling. “So, show me 48,” I said, giving my student a thumbs up.

The student did not articulate audibly everything he had done, but he showed, through writing on the board, what numbers had been used. He had added three to 45, bringing Team A’s number of goals up to 48. Because 45 divided by three is 15, he knew a number three larger would have a quotient only one more when divided by three. In other words 45/3=15… Raise 45+3 to 48, and 48/3=16.

He instinctually got the relationship (the ratio) that caused each rise by three of the dividend to increase the quotient by one.

It was barely a step for this student to double the 16 to make 32. He then added the value of the Golden Snitch (150) to 320, which is how many points 32 goals would equal.

As the student rewrote his addition on the board, other students watched on. They noticed that the math communicator whom I was video recording had accidentally written “16 X 32” on the board. Someone began to point this out, commenting aloud, “Why’d you write sixteen times thirty-two?”

You can hear me tell this observer, “He’s thinking faster than he can write.” I didn’t want my scholar to lose his train of thought. Some students can be heard confirming that they see how 48 would work. At one point the most beautiful “Ah ha” moment can be viewed when a student realizes how the numbers fall into place unlocking the combination to the problem.

I was very proud of this third grader. It thrilled me to capture his “math talk” on video. Not every student understood the concept of ratio this easily, however. For this student, the numbers and ideas just fell into place. For others, the concept was clunky and the numbers were far from lining up neatly.

I tried guiding them through the same math I had already worked through with my fourth graders. They did fine with the computation, but the third graders were lost when it came to understanding the relationship between the two sides of the ratio. Fractions, multiplication, and division are all relatively new concepts for these students. Even though some of them have been multiplying numbers for years, understanding the concept is not long lived.

The students who understood how ratios worked wanted to do more math. They itched to prove themselves masters of arithmetic the way our video star had done. I gave them the new ratio of five to four (5:4), and they jumped on it.

At this point, there were some students who understandably did not know what to do with the five or the four. This was when I took the idea of division and simplified it into forming equal groups to show the relationship between the two sides of the ratio.

“Let’s start off with an easy number,” I suggested. “How about we have Team A score twenty goals.” I wrote a twenty under “Team A” on the board. “If Team A scored twenty goals, and the ratio is five to four, Team B will score more or less?” I figured we could start small.

“Less,” a couple of kids offered.

“Right. How much less might seem tricky to figure out.” The looks on faces told me that they agreed.

An idea occurred to me that I wanted to try. I drew a line of five circles on the board under the number five. I drew four circles under the number four. “What number would you multiply by five in order to make twenty?” I asked. When my students told me four, I wrote the number four inside each of the five circles under the five.

“Remember, ratio means relationship between quantities. That means what we have over here…” I pointed to the five circles with fours inside them, “We must have over here.” I then wrote four inside the four circles under four. “The five fours equals twenty. How much is four fours?” (I know it’s a lot of fours. It feels funny writing four so many times. I contemplated using a different number, but these worked well for [ha ha] my students;)

When they told me that it equaled 16, I wrote that under the four circles. Then, I erased the contents of the circles. I wrote a six in every single circle. “Five sixes equals what?” I wrote a thirty under the twenty. “Four sixes equals what?” Twenty-four got written adjacent the thirty.

An idea occurred to me that I wanted to try. I drew a line of five circles on the board under the number five. I drew four circles under the number four. “What number would you multiply by five in order to make twenty?” I asked. When my students told me four, I wrote the number four inside each of the five circles under the five.

“Remember, ratio means relationship between quantities. That means what we have over here…” I pointed to the five circles with fours inside them, “We must have over here.” I then wrote four inside the four circles under four. “The five fours equals twenty. How much is four fours?” (I know it’s a lot of fours. It feels funny writing four so many times. I contemplated using a different number, but these worked well for [ha ha] my students;)

When they told me that it equaled 16, I wrote that under the four circles. Then, I erased the contents of the circles. I wrote a six in every single circle. “Five sixes equals what?” I wrote a thirty under the twenty. “Four sixes equals what?” Twenty-four got written adjacent the thirty.

One of the students who was working independently had found the answer. When they announced it, we used it to work backward. “What number goes into 80 five times?” With a touch of division we figured out the answer, and I wrote 16 in each circle. “If you have 80 on this side, what number will you have on the other side?” Sixteen times four gives you 64.

To drive home the concept of ratio, I used several other numbers, ending with 500 to 400. “It doesn’t matter how big or how small the quantities,” I explained. “When they are related using the ratio five to four (5:4), they will reflect it by being divisible by five on this side, and four on this side,” I said pointing to the referenced space on the board. “Ratios are easier to understand and work with when we use the smaller numbers, so we reduce both sides to the lowest quotient, using the same divisor. What divisor would we use to reduce 500 to 400?”

While my lesson ended there, here are some ideas for exploring ratios. Compare the land mass between states, countries, counties, or continents. Contrast populations of people or animals.

You could get really scientific with it by exploring the natural ratio between predators and prey. How does nature balance the numbers between the two? Why don’t the predators eat all of the prey? What happens when the ratio becomes unbalanced, and there are too many herbivores? Research the deer population. Find out who is in charge of deciding the number of deer hunters are allowed to kill per season. How do they decide? What would happen if there were many more people getting hunting licenses and more deer than expected disappeared?

Investigate invasive species. What causes something to be considered invasive?

Finally, and perhaps more tame, research the ratio of ingredients in dirt. Some plants require more sandy soils. What is the relationship (ratio) between humus, sand, clay, and other materials in your land? This would introduce ratios with multiple numbers. Students could see that when one number goes up, they all do. Double the dirt, and every variable doubles. That is ratio.