Algebraic notation in chess shows each move that a player makes. Ranks (rows) are notated with numbers, while files (columns) are designated a letter. Thus each of the 64 squares on a chess board has a name, the letter first, followed by the number. For example, the most popular opening in a game of chess is to place a pawn on the square e4. This square is located within the “e” file and on the fourth rank.

In order to show what happened during a chess move players write down not only the square that a piece was moved to, but also what piece was moved and whether something was captured, checked, or checkmated. (There are a couple of other symbols, but these are the major ones.) Abbreviations are used in order to save time. The moves are recorded so that the game can be analyzed and studied afterward. Most chess apps online and on phones will create the notation for you.

The algebraic notation of a chess game looks a lot like code. That’s because it IS! It is a string of commands. If you know how to read it, you could recreate a chess game, move by move. You could plug the code into a computer, as chessgames.com did for “The Game of the Century” between 13 year old Bobby Fischer and International Chess Master Donald Byrne originally played during the Rosenwald Memorial Tournament in New York City, October 17, 1956.

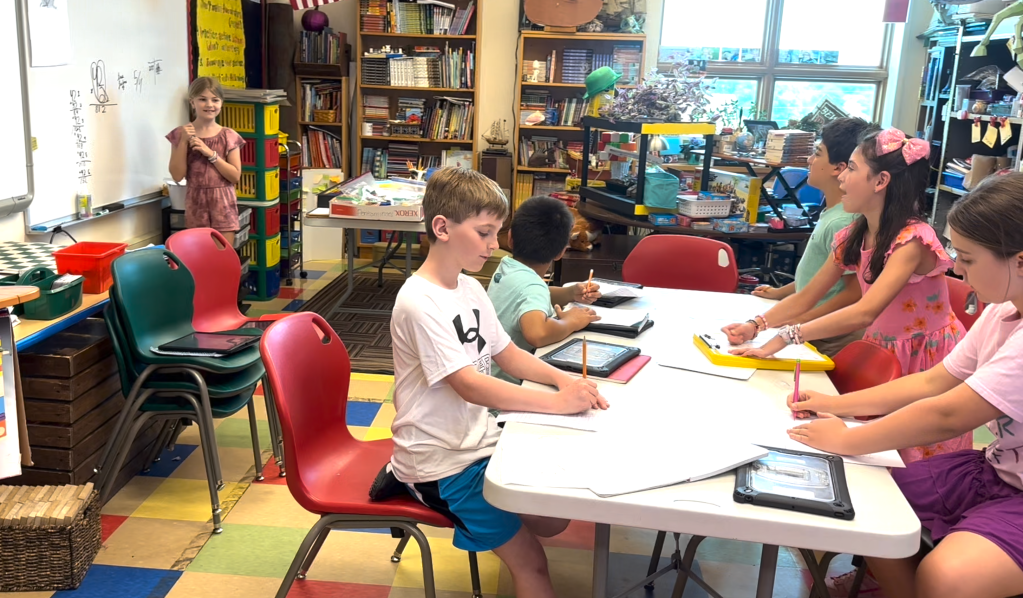

For several years I have been teaching elementary-age kids (7-11) how to play chess. I’ve run a chess club that meets after school. While I always share information about how to read algebraic notation, I don’t require them to use it during play. I want them to learn the game and have fun.

As students get better and begin playing in tournaments, however, they will need to learn to use notation. During competitive play, they will be required to write down the code for each move on a piece of paper. Next to their move, they will also write down their opponent’s moves. In this way, they will be able to “view” the game after its completion. Serious players do this to evaluate each move. Which ones were better than others? Where did I or my opponent falter? What was the critical move? What could I have done differently?

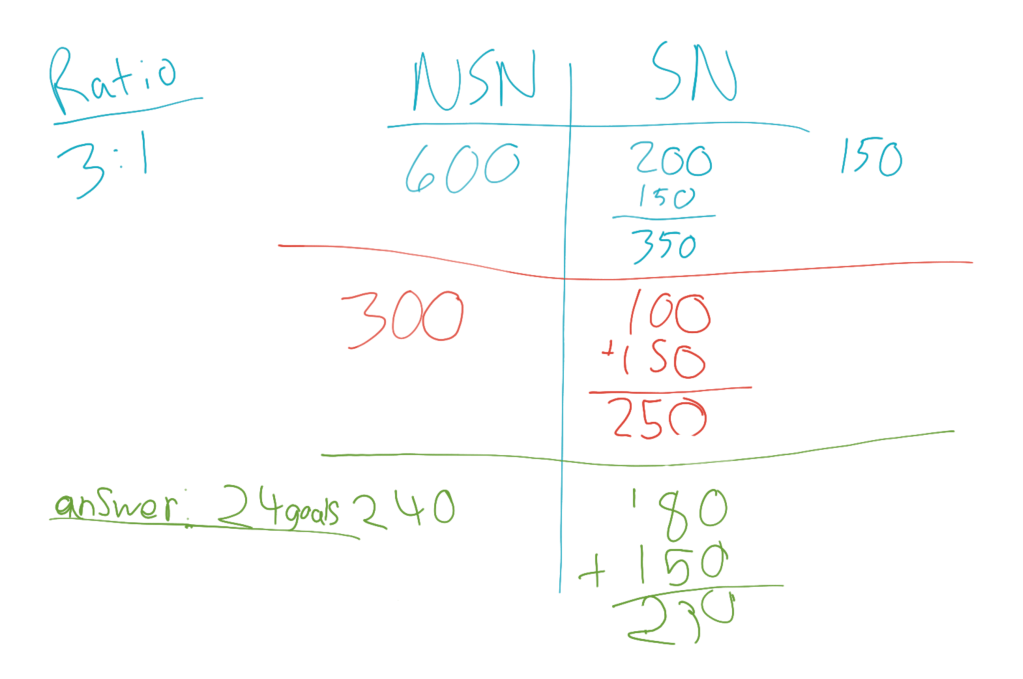

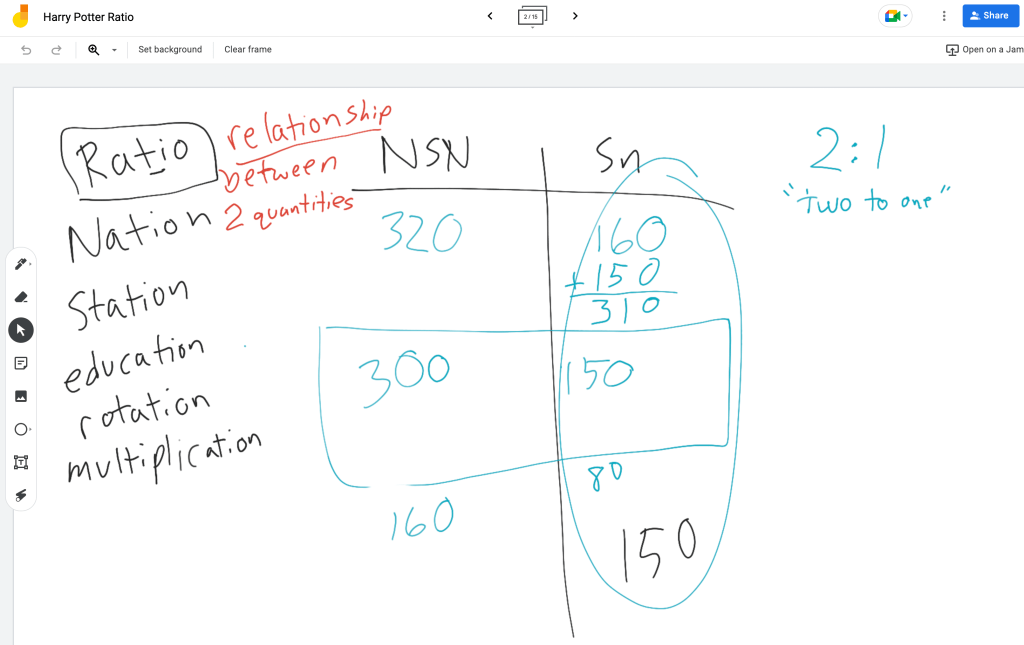

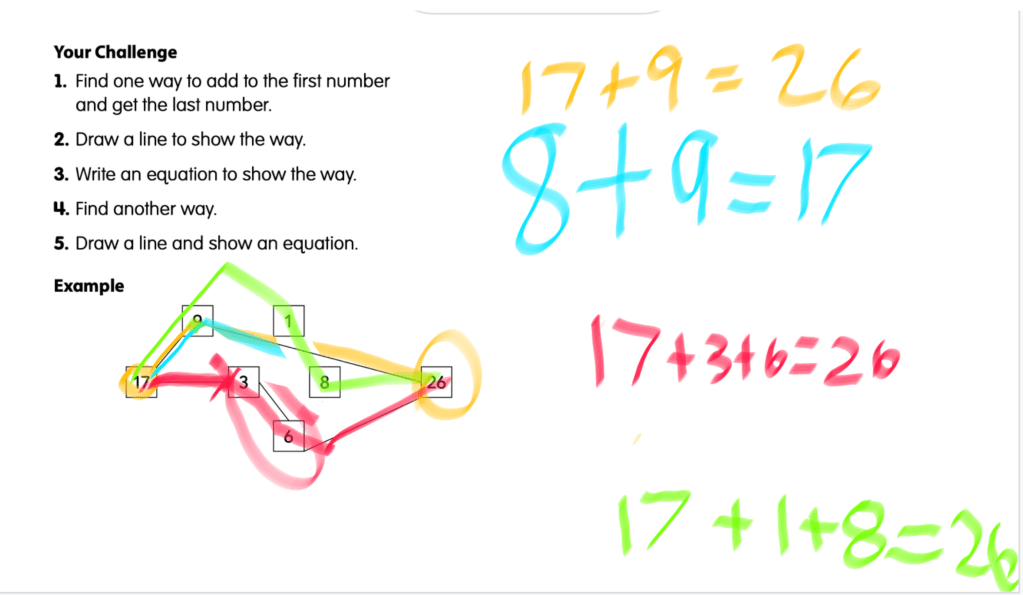

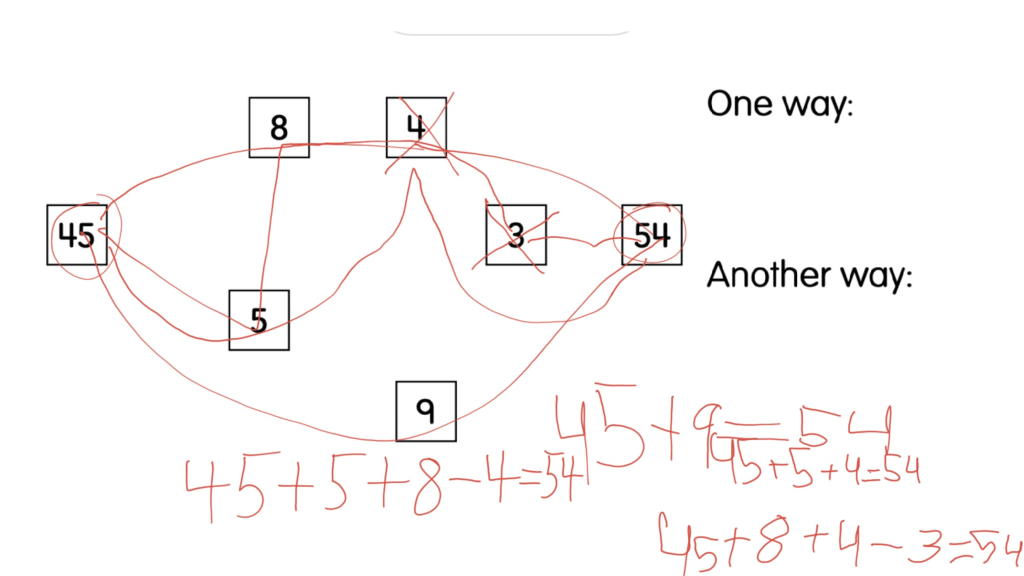

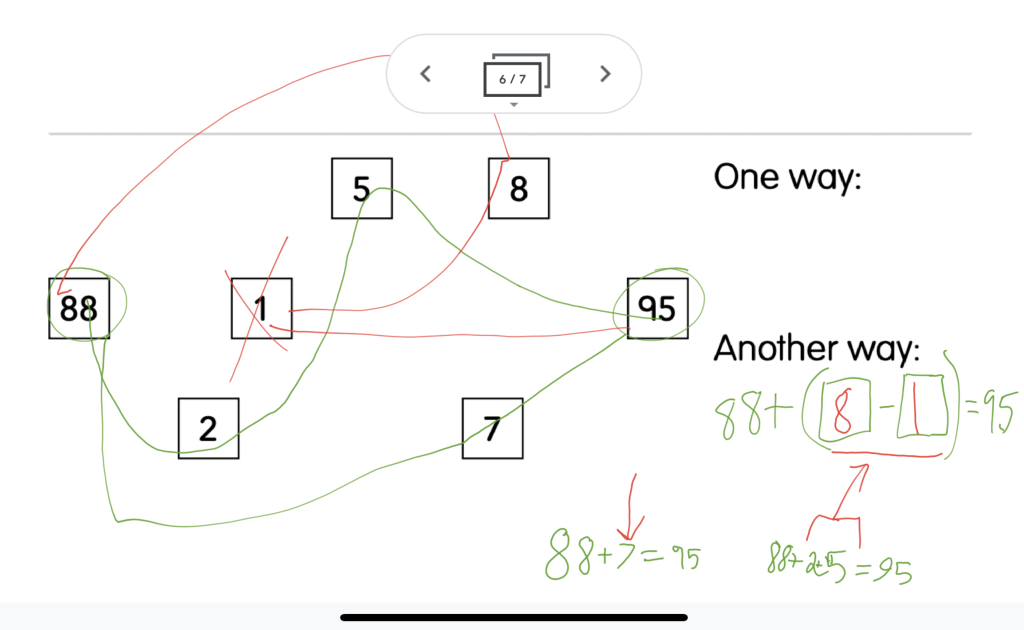

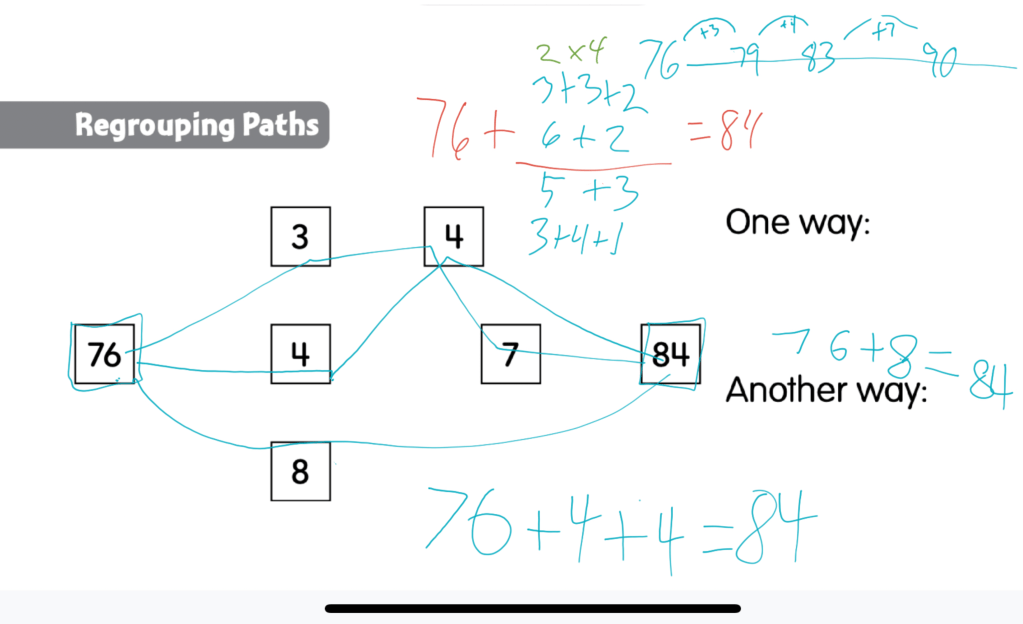

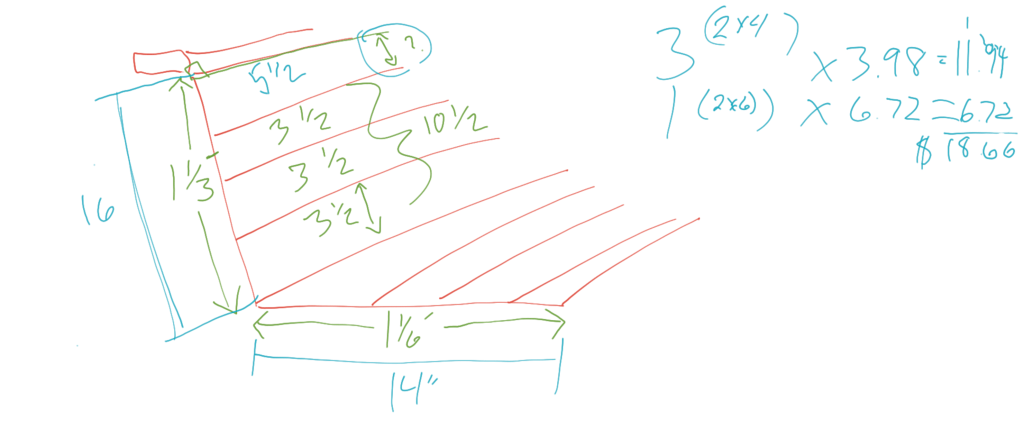

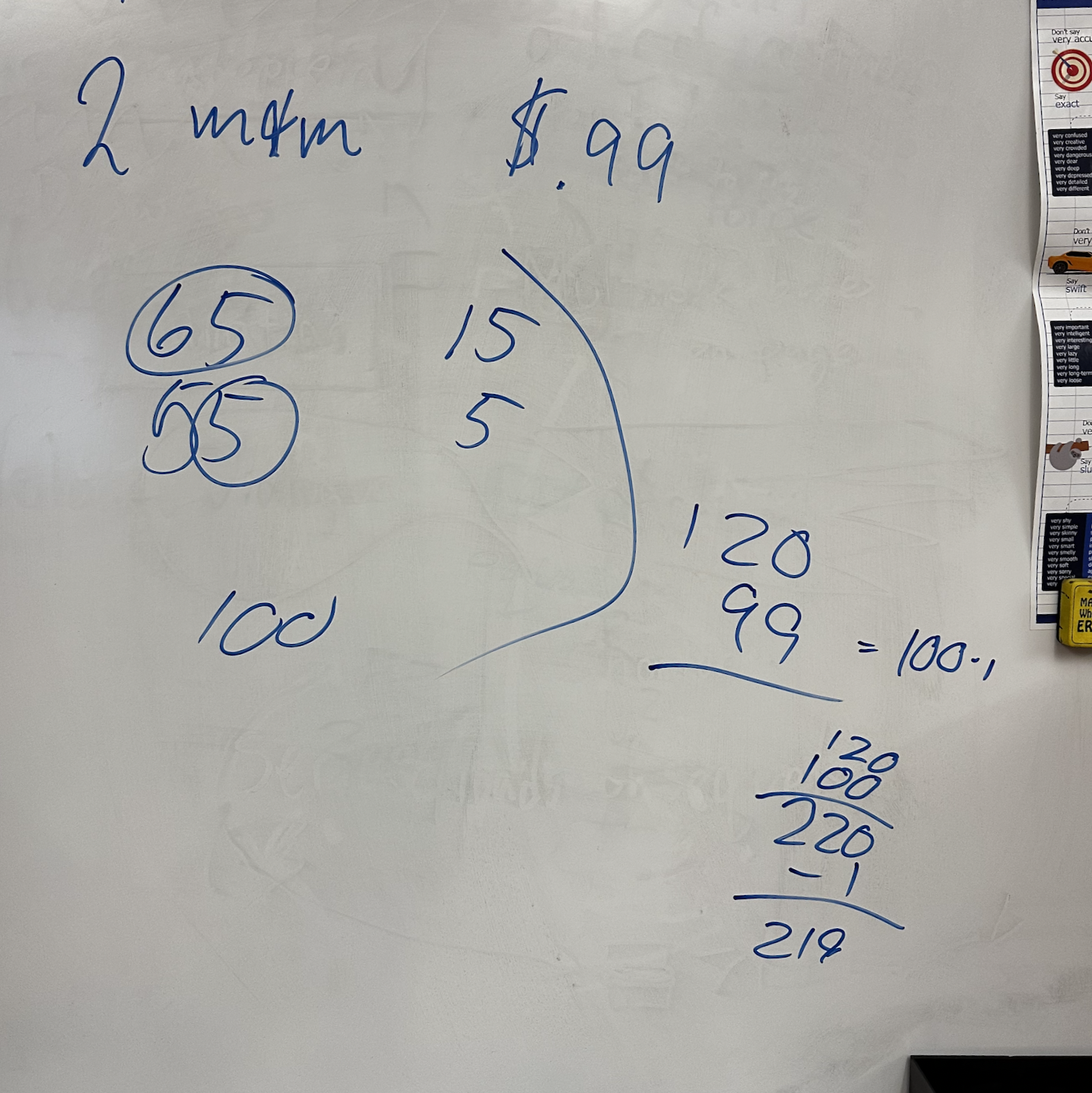

When solving a math problem, it can be valuable to write down some notes. Why? Sometimes you do this to keep short term memory space available. If there are a lot of numbers and a lot of computation is going on, there might be too much to remember in your head. Along the route of figuring out the answer, you write down what you have so far.

Another reason for taking notes can be showing the steps you took to solve the problem. This might help someone else see a path from beginning to end of the math problem, demonstrating how the answer was achieved. They could “replay” the action of solving the problem by reading the steps taken.

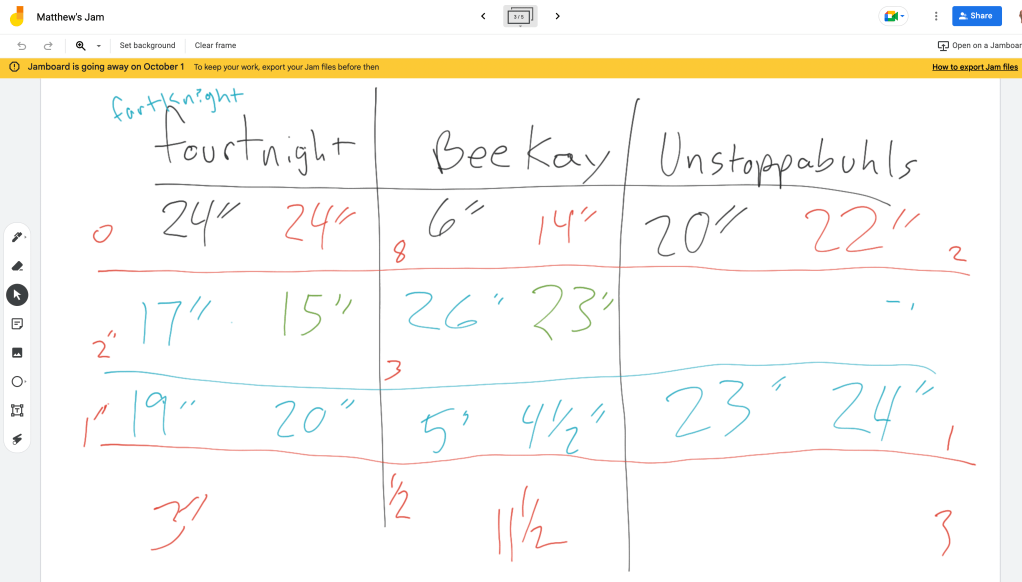

In school, this last “reason” is usually proposed by teachers who want to “see” how you did your work. They say, “Show me your work,” so often that it becomes grating. And, writing down each step of computation can become tedious for a student who just knows the answer. Back in January (2024) I wrote a blog (Part 1) about students communicating their math work creatively. Learning to write down the steps involved in solving a math problem has value, however.

Here are a couple of ideas.

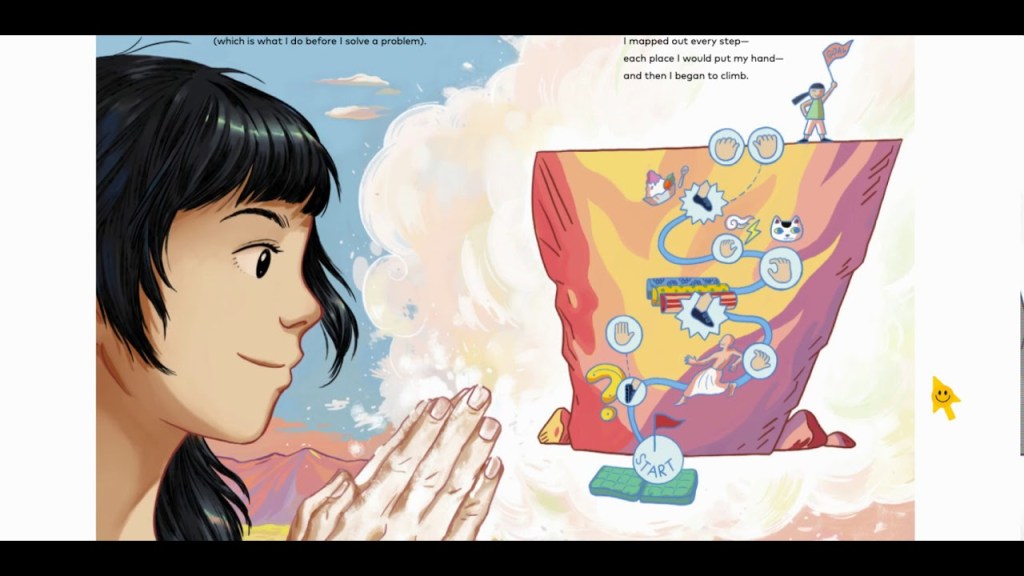

First, instruct students to treat each math problem as though it were a rock-climbing problem. Ashima Shiraishi is a champion of solving problems. She wrote a book about it. “How to Solve a Problem: The Rise (and Falls) of a Rock Climbing Champion” tells the story of 13 year old Ashima figuring out a map that will guide her to the top of Golden Shadow, a V14 boulder in Rocklands, South Africa. The story is an excellent metaphor for not giving up. It also shows how Ashima uses imagery to map out a doable path up the face of a difficult climb. She assigns symbols to the holds and footings that she uses. As she ascends, time after time, for it takes many tries to successfully conquer a difficult problem, she creates a story in her head, using the beneficial symbols (holds), so that she can find her way. The book, illustrated by Yao Xiao, shows (on paper) what Ashima does in her head.

I often see students erase their math when they have tried a set of steps that did not accurately solve a problem. “Don’t do that,” I tell them. “You could very well make the same mistake again. It’s helpful to see what didn’t work, as well as the correct answer. I (and your math teachers) want to see the journey you took, including the fruitless paths.”

Second, teachers ought to present problems that are worthy of their students’ struggle. Ashima Shiraishi has an amazing story of being the youngest person to successfully climb very challenging problems. At the age of 14, she was the first woman (and second person ever) in the world to climb a V15 boulder problem. She has crushed youth competitions, winning several years in a row. When she and illustrator Yao Xaio chose a problem to use for the basis of producing a picture book for kids, they decided on one that was very challenging. Ashima fell many times, having to start over at the beginning. The text shares her process of imaging each place that her fingers or toes would hold as something specific. One was the dot at the end of a question mark. Another was the crook of her dad’s elbow.

What if Ashima used a simple boulder to illustrate her problem-solving skills? One of the most important themes of the short book would be lost; The idea of developing and practicing persistence couldn’t very well be shared if there were no falls.

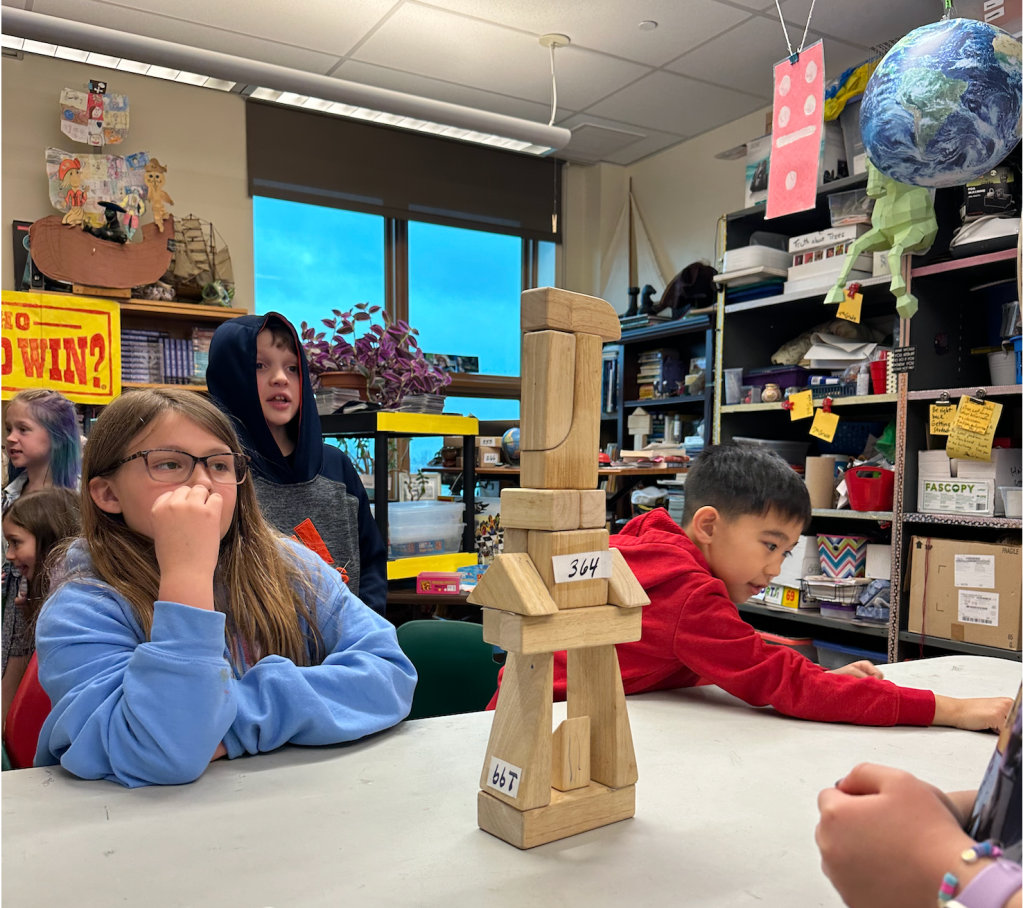

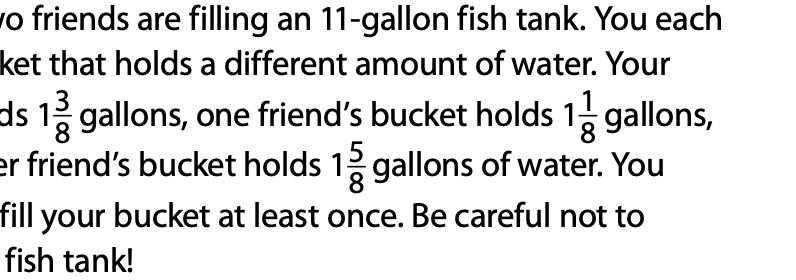

Create fewer math problems that are more challenging. Cause students to have to struggle to conquer each one. If they are required to make memories, it will mean more. If you want your students to “show their work,” give them a problem so complicated that they need to write down notes to get all the way through it.

The math problem should be a challenging chess opponent in a tournament. Your students should have to show each “move,” as they progress through the solution of the problem.

There will be practice problems. These are like the rock-climbing walls that Ashima climbs to stay in shape and hone her skills. She will climb the same wall over and over. She will challenge herself to complete the climb faster with each ascent. A story may be imagined for the short climb, and it could be repeated in her head a hundred times, giving the climb life and familiarity.

This is like memorizing an opening for chess. Increasingly good chess players will learn a variety of initial moves that great players have developed over the years. They will memorize these opening moves through many steps, so that they can anticipate and prepare for potential rebuttals.

In conclusion, if you want your students to show their work, give them something worthy of writing down the steps it took to complete. Teach them how to make the sharing of their math into a story. In the same way that each move in an important chess game is vital to its end, have students think about what they are doing and share the most important parts of the process. You could even have them try to identify the most crucial part(s) of the problem-solving process. With each boulder of a math problem you give them that challenges their minds and they successfully solve, they should develop a hunger for tackling more and more formidable ones in the future.