“I don’t know how I got it; I just know that this is the answer,” a frustrated student defends himself against the inquisition of an even more frustrated teacher who wants him to “SHOW YOUR WORK!”

But, what if he actually doesn’t know where the number came from? We don’t ask the toaster to “Show us how it heats up our bread.” When was the last time you insisted that the mechanic “Show you HOW they fixed your car”? (They always try to explain it to us, and I’m like, “Does it work? How much does it cost? I got stuff to do.” Ha ha;)

I recently had a math enrichment lesson with second graders where I told them what they didn’t know they did with a couple of mental math problems. We were working on comparing three-digit numbers. I had printed pictures of snacks that had prices on them. Teams of students were first asked to arrange the snacks in order from least to greatest price. Then I asked the class to compare the cost of three items to the cost of two others. The students didn’t have paper or anything to write on.

After I received some successful answers, I asked the teams, “What did you do in order to produce those answers?” I got a variety of responses. Most teams told me the names of the operations. “We added the three numbers together, and then subtracted…”

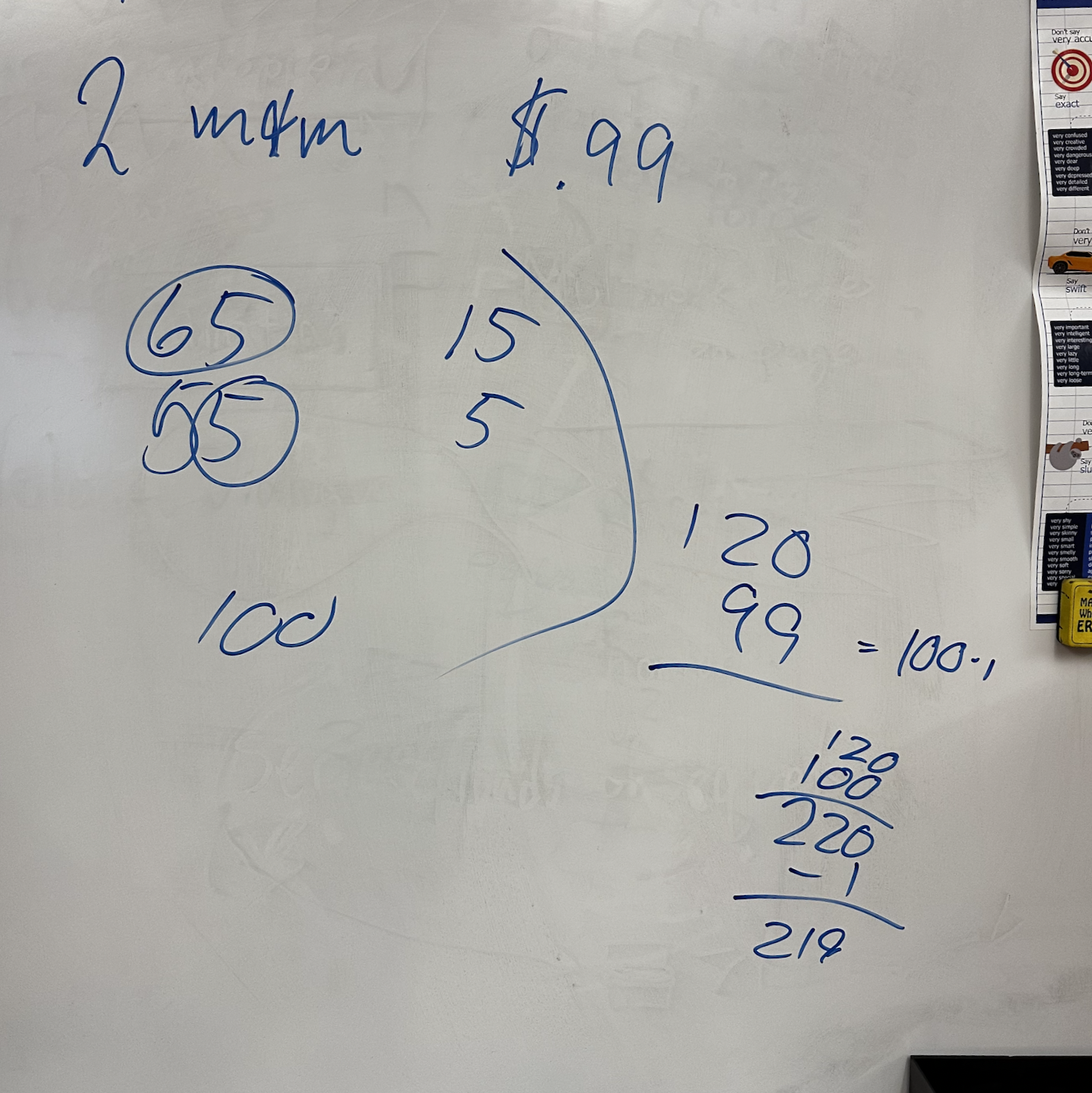

One group explained what they did to complete the operations, and I was very impressed. While students were sharing, I took some notes on the board. I clarified what the group was communicating by drawing circles around numbers and pulling out concepts.

“You began by adding 65 cents to 55 cents,” I reiterated. Nods of heads confirmed the accuracy of my statement. What happens in a creative mathematician’s head is a little different from what one would do on paper, however, and I wanted to pull this out. These students hadn’t used an algorithm.

I like to do a lot of mental math in my room, because it helps kids develop number sense. “The 65 and 55 are both pretty close to a number that is really easy to add in your heads,” I told them.

“Fifty!” the group called out. We have been identifying compatible numbers, so they already knew to look for something more manageable.

“That’s right. And, in order to get to fifty, you have to adjust these a little.” I circled the 65 and wrote 15 on the side. Then I circled only the 5 from the ones of 55, and I wrote that near the 15.

If a student had paper in front of them, they might line up 65 and 55. Then they’d add the fives from the ones’ column and regroup with a “one” above the tens column… But, do we grown ups do this in the grocery store when we are comparing one item with another? No, we use mental math. We develop creative tricks that we may not even realize we use!

My aim is to unlock this mathematical creativity early in life. A secondary goal is to help students be able to communicate it.

“After adding the two 50s together, what did you do?” Everyone can see that there is still a 15 and a 5 written on the board. I wrote the sum before anyone called out, answering the rhetorical statement myself. “Now, you need to add this $1.20 to 99 cents. That sounds hard,” I teased, knowing that they’d already smashed that algorithm in their minds.

When I told them about using 100 instead of 99, several students silently shouted, “That’s what I did!” No one is going to carry a one from the tens to the hundreds column of a mentally constructed algorithm. And, we don’t always have paper. AND, do you really want to teach your students to be dependent on paper?!

Now, think about it, reader. Students are using subtraction in order to add numbers together. What 8 year old is going to be able to explain this abstract use of arithmetic in writing on a test or assessment?

And, we (myself included) expect them to “Show their work!” I’m happy if they know what they are doing and get the correct answer. I’m nearly 50, and I only just learned how to show MY own work! LOL

What I found myself doing in the past was asking students who had performed mental gymnastics to achieve a remarkable mathematical feat to write down the steps they took. In other words, if you added up three numbers (65 + 55 + 99), and then subtracted a fourth from that sum, write it all down…

Even if you can’t describe the exact process of creating the sum or exactly what you did to subtract. Just tell me what you did with the numbers. I, like every other math teacher in the world, wanted to see more than just an answer!

I think that having students use mental math, and then having them explain what they did VERBALLY is helpful in sharing the mechanics of the creative math. It’s easier to verbalize than it is to write. I bet there are books written about this. (If you know of any, please share. Thank you.)

A tool I’ve enjoyed having students use to verbally communicate their creative math skills is Flip (formally known as Flipgrid). Kids can make videos of themselves talking about the math. They can also write on their screens to show what they did while talking about it. If they did the math on paper, they can take a photo of their work to include in their video. Finally, they can watch each other’s videos, get ideas for future creative math projects, and leave encouraging replies to each other. The platform is easy to navigate and teacher-friendly for leaving feedback and assessment info.

In conclusion, while I always instinctually knew that forcing a kid to write down everything they did in their head could squash their creativity, I never knew how to bridge the gap between teacher and student; The chasm between the answer (what the student produces) and the process (what the teacher cares most about) before now. I’d tried varying techniques with varying results. My new thing is to verbally walk them through tricks I’d use to do mental math. Through this process, they recognize some of what they are already doing in their minds. They are learning how to communicate it. And, some students are learning creative ways to play with numbers.

One thought on “Communicating Creative Mental Math Verbally”